Introduction: Lao Tzu and the Ancient Greeks

My teachings are very easy to understand and to practice; yet there is no one in the world who is able either to understand or to practice them. This is because my teachings have an originating principle and arise from an integrated system. This is not understood, so I am unknown.

– Lao Tzu (Gi-ming Shien, trans.)

Of the Logos, which is as I describe it, people always prove to be uncomprehending, both before and after they have heard of it. For although all things happen according to this Logos, people behave as if they have no experience, even when they experience such words and deeds as I explain, when I distinguish each thing according to its constitution and declare how it is. The rest of humanity fails to notice what they do after they wake up just as they forget what they do when asleep.

– Heraclitus

1. The Tao/Logos

Christ the Eternal Tao was inspired by the life of the Chinese scholar Hieromonk Seraphim Rose (then known as Eugene Rose), and by his teacher, the philosopher Gi-ming Shien. In Gi-ming’s transmission of the ancient Chinese tradition, one is struck by how closely it resembles the ancient Greek tradition; and Gi-ming in fact taught that the early Chinese and Greek philosophers were basically alike in their view of the universe.

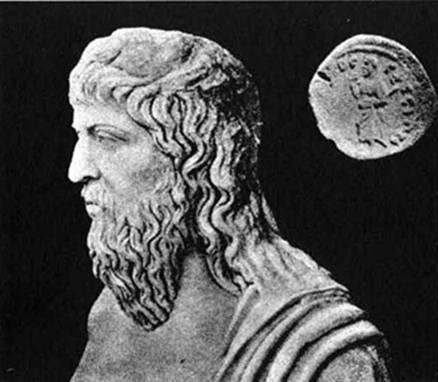

Heraclitus of Ephesus (ca. 540–480 B.C.). Statue of the second century A.D., copied from the original of the fifth century B.C.

«In the history of ancient China», Fr. Seraphim said, «there are moments when it is absolutely incredible how the same things happened in Chinese life as happened in the West, even though there was no outward connection between the two civilizations. The first of the Greek philosophers – Thales and so forth – lived about the sixth century B.C., just about the time Confucius was in China and Buddha was in India. It is as though there really was a spirit of the times».

Heraclitus, born in the middle of the sixth century B.C., was one of these first Greek philosophers. For the riddling character of his writings, he was surnamed «the Obscure» even in antiquity. He based his philosophy on the «Logos» – a word which itself means «Word», but which bears the connotations of measure, proportion, and pattern. The Logos of Heraclitus, according to one textbook of Greek philosophy, «is the first principle of knowledge: understanding of the world involves understanding of the structure or pattern of the world, a pattern concealed from the eyes of ordinary men. The Logos is also the first principle of existence, that unity of the world process which sustains it as a process. This unity lies beneath the surface, for it is a unity of diverse and conflicting opposites, in whose strife the Logos maintains a continual balance.... The Logos maintains the equilibrium of the universe at every moment»3. Although Heraclitus taught that «all things change, and nothing remains at rest», he knew the Logos to be itself stable, the measured pattern of flow.

At about the same time that Heraclitus lived in Greece, there lived in China the philosopher Lao Tzu («Old Master»). Lao Tzu wrote of the same universal Pattern or Ordering Principle that Heraclitus styled the Logos. «I do not know its name», he said, «but characterize it as the Way (Tao)»4 – the Tao being a symbol basic to Chinese thought,5 as the Logos was to ancient Greek thought. For Lao Tzu, the Way was precisely what its adopted name signified, in its full metaphysical sense: the Way, Path or Pattern of Heaven, the Course that all things follow. The Way is the Uncreated Cause of all things. It is the Way that creates, and it is the Way that «nourishes, develops, cares for, shelters, comforts, and protects»6 the creation, balancing the strife of opposites by itself not contending.

Of the writings of Heraclitus, only a handful of fragments have come down to us; but from Lao Tzu we have a full eighty-one chapters of the Tao Teh Ching. Of all the ancient philosophers, Lao Tzu came the closest to assimilating the essence of reality and describing the Tao or Logos. His Tao Teh Ching represents the epitome of what a human being can know through intuition, through the apprehension of the universal Principle and Pattern manifested in the created order.

Six centuries after Heraclitus and Lao Tzu, there lived on the Greek island of Patmos an old, white-haired hermit named John. While exiled in a cave on the island, he dictated to his disciple Prochorus what he had received from direct revelation from the heavenly realm, from Divine vision, and thus spoke to the world words that it never thought to hear:

In the beginning was the Logos,

And the Logos was with God,

And the Logos was God.

The same was in the beginning with God.

All things were made by Him;

And without Him was not anything made that was made.

In Him was life, and the life was the light of men.

And the light shines in darkness,

And the darkness comprehended it not....

He was in the world, and the world was made by Him,

And the world knew Him not....

And the Logos became flesh,

And dwelt among us,

And we beheld His glory.7

This was that very Logos of which Heraclitus had said the people «always prove to be uncomprehending»; this was the very Tao that Lao Tzu had said «no one in the world is able to understand». It is not without reason that sensitive Chinese translators of St. John’s Gospel, knowing that «Tao» meant to the Chinese what «Logos» meant to the Greeks, have rendered the first line of the Gospel to read: «In the beginning was the Tao»8.

St. John the Apostle dictating his Gospel to his disciple Prochorus on the Greek island of Patmos. Russian icon of the seventeenth century.

St. John the Apostle of Christ, who authored the Book of Revelation as well as the Gospel of John. Sixteenth-century icon from the Monastery of St. John on the island of Patmos, built over the cave in which he lived and received Divine revelation.

When the Apostle John wrote his Gospel, he was no doubt aware of the common Greek philosophical symbol of the Logos. But – as can be clearly seen by a comparison of that Gospel with the riddles of Heraclitus or the writings of other philosophers – when he spoke from revelation he was not merely borrowing an old term; rather, he was transforming it, bringing it into the light of the fullness of mystical knowledge. When he spoke of the Logos, it was now no longer in riddles, as from one who had only glimpsed its traces in nature. For now the Logos – the Creator, Sustainer, Pattern and Ordering Principle of nature – was made flesh, and dwelt among us, for the only time in history. And John, His disciple, had seen Him; he had beheld His glory and heard the words which proceeded from His mouth. Being offered the ultimate closeness to Him Who had only been dimly seen before, he had even lain on His breast and, in the greatest of mysteries, had received Him into himself at the Last Supper.

Thus, while Lao Tzu’s Tao Teh Ching represents the highest that a person can know through intuition, St. John's Gospel represents the highest that a person can know through revelation, that is, through God making Himself known and experienced in the most tangible way possible.

Gi-ming Shien conducting a class in Chinese philosophy in 1956 at the Academy of Asian Studies, San Francisco, where Fr. Seraphim first studied under him. Later Gi-ming became Fr. Seraphim’s private tutor in ancient Chinese language and philosophy.

2. Hieromonk Seraphim and Gi-ming Shien

Growing up in the late 1940s and early 1950s, the aforementioned Fr. Seraphim rejected the modern American Christianity in which he had been raised, finding it to be boring, sterile and empty. In quest of a true apprehension of reality, he undertook an extensive study of the ancient Chinese tradition, first under Alan Watts and then under a more authentic transmitter of this tradition, the humble and virtuous Gi-ming Shien. Gi-ming had studied under sages in China (among whom were Ou-yang Ching-wu and Ma Yei-fu), as well as with some of the greatest Chinese thinkers of the twentieth century. Under his tutelage, Fr. Seraphim learned ancient Chinese in order to study the Tao Teh Ching in the original language. He helped Gi-ming to translate the Tao Teh Ching into English, and Gi-ming opened to him the deeper meaning of its contents. It was Gi-ming who first told Fr. Seraphim that the Logos of the ancient Greeks is the same as the Tao of Lao Tzu.

Fr. Seraphim (then Eugene) Rose in 1963

From the writings of the French metaphysician René Guénon, Fr. Seraphim had learned the necessity of adhering to the traditional, orthodox form of a religion. This enabled him to value Gi-ming as an orthodox representative of the Chinese tradition; and then led him finally – unexpectedly – back to the ancient, orthodox form of the religion he had rejected in his younger days. Just as the ancient Greeks had once seen the fulfillment of their philosophy in the revelation of Christ, so Fr. Seraphim recognized the fulfillment of the philosophy of Lao Tzu in the ancient Orthodox Christianity that the Greeks (and, by extension, the Russians) had preserved.

Gi-ming Shien later disappeared mysteriously, to the great sadness of Fr. Seraphim, who to the end of his days remembered him with the deepest admiration and gratitude. Fr. Seraphim went on to become an Orthodox Christian monk and writer in the mountains of northern California, and since his death in 1982 he has unexpectedly become one of the best-loved spiritual writers in Russia. It was through him that the writer of the present book discovered the depth of ancient, unadulterated Christianity, and along with Fr. Seraphim found it to be the fullness of what he had been probing for in Lao Tzu. This book is an offering to those of like mind, who have found much of contemporary American Christianity to be trivial and cliché, and yet who still have a longing for Christ. Through the wisdom of ancient, God-illumined Christian teachers, whom we have quoted extensively, we will show that Christ’s revelation is indeed the consummation of what had been glimpsed by the great pre-Christian sages.

Fr. Seraphim’s notes from Gi-ming Shien’s class discussion of chapters 52 and 51 of the Tao Teh Ching, in which Gi-ming equated the Tao with the Logos and defined Teh as the «realizing principle» of the Tao (see p. 238 below). November 11, 1957.

Hieromonk Seraphim Rose (1934–1982) at the St. Herman Monastery in the mountains of northern California, 1978.

3. Modern Syncretism vs. Ancient Apologetics

This book’s comparison of the Tao Teh Ching with Christian Scriptures opens it up to the accusation of being merely another attempt at religious syncretism. A serious reading of the text, however, will bear out that this is not the case. Religious syncretism, in its modern form, regards all paths as possessing equal truth simultaneously, and in so doing is forced to overlook certain basic distinctions, or to offer complicated explanations in order to rationalize these distinctions away. The ancient Christian teachers, on the other hand, took a more honest and discerning approach, which in the end proved to be more simple, natural, and organic. Rather than mixing all the religions together like the moderns do, these ancients understood that there was an unfolding of wisdom throughout the ages. They saw foreshadowings, glimpses and prophecies of Christ not only among the ancient Hebrews, but also among other peoples who lived before Him, and they saw the writings of pre-Christian sages as a preparation for Christ as the apogee of revelation. This is explained most clearly in the quote by St. Seraphim which begins this book9. If we concede that the pre-Christian philosophers did seek the truth, and that they did catch glimpses of it, it only stands to reason that their teachings should bear some similarities, like a broken reflection of the moon in water, to the fullness of Truth in Jesus Christ. Therefore, these similarities need not appear as a threat to Christianity; instead, they offer one more proof of Christ as universal Truth.

Christ the Eternal Tao, then, should be seen as following not in the modern syncretic tradition, but rather in the ancient apologetic tradition. The latter began less than a century after Christ, with St. Justin Martyr (A.D. 110–165), Clement of Alexandria (A.D. 153–217), and Lactantius (A.D. 260–330).

In speaking to the Greek polytheists of his time, St. Justin called upon the testimony of the pre-Christian Greek philosophers and poets who, like Lao Tzu, taught that there are not many gods, but only one God: the Uncreated Cause and Creator of the universe, omnipotent, eternal, and infinite10. Each of these writers, Justin affirmed, «spoke well in proportion to the share he had of the Logos disseminated among people, seeing what was related to it.... For all the writers were able to see realities darkly through the sowing of the implanted Logos that was in them»11. Elsewhere Justin went so far as to call the pre-Christian sages by the name of Christian: «Those who lived in accordance with the Logos are Christians, even though they were called godless, such as, among the Greeks, Socrates and Heraclitus and others like them.... So also those who lived before Christ and did not live by the Logos were ungracious and enemies of Christ, and murderers of those who lived by the Logos. But those who lived by the Logos, and those who so live now, are Christians, fearless and unperturbed»12.

St. Justin Martyr, the Philosopher (A. D. 110–165).

In the generations immediately after Justin, Clement and Lactantius continued in this tradition by pointing to ancient writers who believed in one God13 Among the philosophers they cite is Hermes Trismegistus, who, like Lao Tzu, says that the Creator is «one, self-existent, and without a name»14.

«The Greeks», says Lactantius, «speak of God as the Logos... for Logos signifies both speech and reason, inasmuch as He is both the voice and the wisdom of God. And of this Divine speech not even the philosophers were ignorant, since Zeno represents the Logos as the arranger of the established order of things, and the framer of the universe: whom he calls Fate, and the necessity of things, and God, and the soul of Jupiter, in accordance with the custom, indeed, by which they are wont to regard Jupiter as God. But the words are no obstacle, since the sentiment is in agreement with the truth»15.

Justin and Lactantius praised Socrates because, again like Lao Tzu, he refrained from setting forth precise, defined teachings about those things which had not been shown to him through Divine revelation. In the spirit of Lao Tzu, Socrates had said: «It is neither easy to find the Father and Maker of all, nor, having found Him, is it possible to declare Him to all»16. They also extolled Socrates for not paying homage to the false gods whom the state recognized and all the people worshipped – and for even being killed for this. This was because, writes Justin, «Christ was partially known even by Socrates, for He was and is the Logos Who is in every person»17.

Over and above the sayings of the philosophers, the sayings of the ten virgin prophetesses known as Sibyls were cited by ancient Christian writers as pointing to belief in the one invisible God and offering clear prophecies of the coming of Christ. Virgil, who died nineteen years before the birth of Christ, used the prophecies of the Sibyl of Cumæ to predict (in his fourth Eclogue) that the Messiah would «come down from heaven», be born as an infant from a virgin, and bring in an age in which «all stains of our past wickedness would be cleansed»; and that all this would take place during the reign of Virgil’s friend, the consul Pollio18. This indeed occurred.

In quoting from sages who lived before Christ, Justin, Clement and Lactantius corrected their mistakes, which they attributed to the times in which these sages lived. «Whatever either lawgivers or philosophers uttered well», says Justin, «they elaborated by finding and contemplating some part of the Logos. But since they did not know the whole of the Logos, which is Christ, they often contradicted themselves»19. And Lactantius writes: «People of the highest genius touched upon the truth, and almost grasped it, had not custom, infatuated by false opinions, carried them back»20. At the same time, both Justin and Lactantius embraced the truths uttered by the ancient sages as their own. «Whatever things were truly said among people», Justin affirms, «belong to us Christians»21.

Neither Justin, Clement nor Lactantius could have heard of Lao Tzu. From what has been said above, however, there can be no doubt that, had they lived in China rather than in the Greek and Roman world, they would have brought forth Lao Tzu as a pre- Christian witness of Christ the Logos.

In ancient Greek, Bulgarian and Romanian Orthodox monasteries and churches today, one can find wall-paintings of the ancient Greek philosophers, who are thus honored as seekers of Truth before the coming of Christ. Even the staunchest Christians in Greece refer to Socrates as «the Apostle to the pagans». The best-loved Greek saint of the twentieth century, St. Nektarios of Pentapolis, said that Socrates and «divine Plato» were at times «inspired by God»22. If the Greek philosophers can be honored in this way, cannot also Lao Tzu, who came even closer than they to describing the Logos, the Tao, before He was made flesh, and dwelt among us?

The Greek philosopher Pythagoras (ca. 578–510 B.C.). Wall-painting by the most renowned Greek iconographer of modern times, Photios Kontoglou, 1932. In his Ekphrasis of Orthodox Iconography, Kontoglou writes: «The old icon painters sometimes painted in the narthex of churches these wise Greeks, because they foresaw the dispensation of Christ’s Incarnation».

Left to right: Aristotle (384–322 B.C.), a Sibyl (virgin prophetess), and Plato (ca. 428–348 B.C.). Wall-painting from Bachkovo Monastery in Bulgaria, ca. A.D. 1640.

Seal script from the Shang-Yin dynasty, ca. eleventh century B.C.

Seal script from the Eastern Chou dynasty, ca. 422 B. C.

* * *

Примечания

Reginald E. Allen, ed., Greek Philosophy: Thales to Aristotle, pp. 9–10.

Tao Teh Ching, ch. 25 (Gi-ming Shien, trans.).

See Thomas Cleary, The Essential Tao, p. 1.

Tao Teh Ching, ch. 51 (Gia-fu Feng and Jane English, trans.).

The identification of “Tao” with “Logos” has not only a philosophical but also a Scriptural basis. In St. John’s Gospel, Christ the incarnate Logos calls Himself “the Way (Tao)” (John 14:6); and in the Acts of the Apostles we read how the first followers of Christ referred to their new faith simply as “the Way” (sec Acts 19:9, 19:23, 22:4, 24:14, 24:22).

See p. above.

Among those whom Justin mentions are: Orpheus (in the work called Diathecæ), Sophocles, Pythagoras, Plato, Ammon, / Æschylus, Philemon, Euripides and Menander.

St. Justin Martyr, “Second Apology”, in The Ante-Nicene Fathers, vol. 1, p. 193.

Ibid., “First Apology,” p. 272.

In addition to the writers cited by Justin, Clement and Lactantius cite Virgil, Ovid, Thales, Anaxagoras, Antisthenes, Cleanthes, Chryssipus, Zeno, Democritus, Xenophanes the Athenian, Hesiod, Aristotle, Cicero, and Seneca.

Lactantius, “The Divine Institutes”, in The Ante-Nicene Fathers, vol. 7, p. 15.

Ibid., p. below.

Plato, Timaeus. Quoted in St. Justin Martyr, “Second Apology”, p. 191, and in Clement of Alexandria, “Exhortation to the Greeks”, in The Ante-Nicene Fathers, vol. 2, p. 191. See also Lactantius, p. 91.

St. Justin Martyr, “Second Apology”, p. 191.

On the Sibyls, see St. Justin Martyr, “Hortatory Address to the Greeks,” in The Ante-Nicene Fathers, vol. 1, pp. 288–89; Clement of Alexandria, op. cit., 192, 194; and Lactantius, op. cit., pp. 15–18, 26–27, 61, 105, 210, 215. For a discussion of the Sibylline prophecies of Christ contained in the fourth Eclogue of Virgil, see “The Oration of Constantine” in The Nicene and Post-Nicene Fathers, vol. 1, pp. 575–77.

St. Justin Martyr, “Second Apology”, p. 191.

Lactantius, “Divine Institutes”, p. 15.

St. Justin Martyr, “Second Apology”, p. 193.

St. Nektarios of Pentapolis, Christologia, pp. 14, 18, 20. Quoted in Constantine Cavarnos, Meetings with Kontoglou, p. 53.