7. Humanity as Hypostasis of the Universe

Defining the Humankind-Event – The Humankind-Event and the Anthropic Principle – Hypostatic Dimension of the Humankind-Event – From Anthropic Transcendentalism to Christian Platonism – Intelligibility and Meaning of the Universe: The Participatory Anthropic Principle – The Humankind-Event and the Incarnation – The Universe as Hypostatic Event

There are in personality natural foundation principles which are linked with the cosmic cycle. But the personal in man is of different extraction and of different quality and it always denotes a break with natural necessity… Man as personality is not part of nature, he has within him the image of God. There is nature in man, but he is not nature. Man is a microcosm and therefore he is not part of the cosmos.

– Nicolas Berdyaev, Slavery and Freedom, pp. 94 – 95

The fact that the universe has expanded in such a way that the emergence of conscious mind in it is an essential property of the universe, must surely mean that we cannot give an adequate account of the universe in its astonishing structure and harmony without taking into account, that is, without including conscious mind as an essential factor in our scientific equations… Without man, nature is dumb, but it is man’s part to give it word: to be its mouth through which the whole universe gives voice to the glory and majesty of the living God.

– Thomas F. Torrance, The Ground and Grammar of Theology, p. 4

This chapter develops the idea that the phenomenon of intelligent human life in the universe, which we call the humankind-event, is not entirely conditioned (in terms of its existence) by the natural structures and laws of the universe. The actual happening of the humankind-event, which is treated as a hypostatic event, is contingent on nonnatural factors that point toward the uncreated realm of the Divine. We develop an argument that modern cosmology, if seen in a wide philosophical and theological context, provides indirect evidence for the contingency of the universe on nonphysical factors, as well as its intelligibility, established in the course of the humankind-event, which is rooted in the Logos of God and detected by human beings through the logoi of creation. The universe, as experienced through human scientific discursive thinking, thus becomes a part of the humankind-event; that is, the universe itself acquires the features of the hypostatic event in the Logos of God.

Defining the Humankind-Event

Before we discuss the anthropic inference in cosmology, we must look at the phenomenon of human life from a cosmological perspective. We intentionally talk about human life but not about biological life in general, for we are interested here in the meaning of human conscious life, life that has not only natural (physical and biological) dimensions but also hypostatic dimensions, whose essence is to affirm that human beings are not isolated creatures but are relational beings, whose personhood is formed through the relationship of these beings to one another as well as to the source of their existence in the Divine. Thus the phenomenon of human life in the cosmos is to be seen from the point of view of the whole economy of salvation of man, which includes the creation of the world and its redemption and ultimate transfiguration.

This is why we want to separate the issue of biological forms of life in the universe in general from the particular issue of the existence of intelligent human beings, who are able to contemplate the overall order in the universe, its meaning, and to detect the transcendent source of this order, and who can have beliefs and purposes, which can influence their own nature as well as nature of the whole universe.430 Theology contemplates the meaning of human life as that of persons in their relationship to one another and to God. It characterizes humans, who were created in the image of God, through the view that the line that demarcates creature and creator cannot be abolished, yet human beings have the potential of self-transcendence to attain the likeness to God (that is, to be deified). It is through this hypostatic mode of existence that human beings are capable of gratitude to God for creation and can offer the world back to the Creator in thanksgiving, contemplating thus, through their eucharistic function, the meaning of the whole world as God’s good creation.431

What we are affirming here is that the phenomenon of man, if seen from a wide perspective, is not something that is inherent in the story of a large and various universe but, rather, is an event in the whole cosmic history (as understood now by modern cosmology). This event is unique not only in a sense of the fine-tuning of some particular aspects of its happening in the universe but literally as the unrepeatable experience of existence in the universe, which cannot be modeled scientifically in different places and different ages of the universe. Our aim, then, is to assert that the whole experience of the world, which is performed by humankind, is a flash of the cosmological memory, incarnate in a particular place in the universe for a fixed aeon, destined to disappear in order to fulfill its eschatological destiny.

Thus the humankind-event can be treated similarly to the Christ-event as a happening of an extraordinary nature, requiring for its explanation the appeal to transnatural principles that will have to elucidate not only the reasons for the humankind-event to happen but also the ultimate purpose of this event for the fate of the entire universe.

When we insist that the phenomenon of humanity is the event, we want to make it clear that there is an element of historicity in it, that is, some fundamental, irreversible change in the history of the universe that makes the emergence of human life in the universe not a blind fact of chance but, rather, a hypostasized existence that is fundamentally different compared with other forms of matter and different forms of biological life.

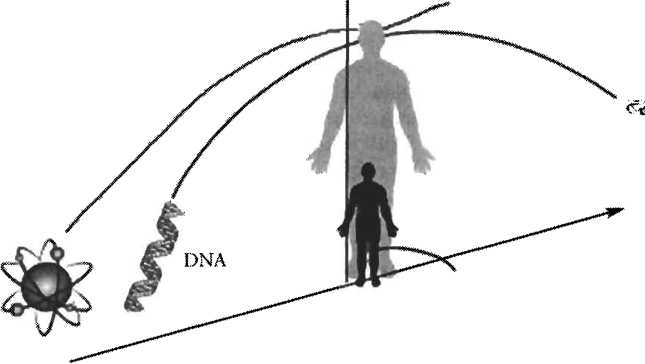

In order to convince the reader of this claim, we start with a simple observation: that the phenomenon of man, if seen from a cosmological perspective (that is, from the point of view of the place and age it occupies in the overall history of the universe), and simply in physico-biological terms, represents a tiny island in the vast ocean of physical being. Indeed, according to modern cosmology, the universe is old and large. Its estimated age T varies from between 10 and 15 billion years, and its maximal observable size, corresponding to the distance that light can travel during the time T, is equal to RU ≈ 1028 centimeters. If we accept that the humanoid type of life appeared on the earth approximately 1 million years ago, it is not difficult to estimate, in relative units, that the amount of time that human life exists in the universe ∆t with respect to the age of the universe T is

∆t/T ≈ 10–4.

As to the relative space occupied in the universe by humankind (we mean the earth, with a radius of RE ≈ 109 centimeters), the ratio will be even more impressive:

RE/RU ≈ 10–19.

It is not difficult to realize that the volume occupied by humans on the earth will be ≈ 10–57 of the volume of the observable universe. The illustration in figure 7.1 makes these calculations even more impressive.

Figure 7.1

It is important to realize that the universe, being old and large, was unsuitable for the existence of human life most of the time and is probable unsuitable for life in most of its space (assuming, of course, that when we think about humankind, we mean exclusively our own civilization, refusing any speculations about extraterrestrial intelligent life). This brings us to the conclusion that the universe, understood as overall space-time, is effectively empty and dead in terms of life, with only one exception, the life on the earth.

We can easily illustrate this point by appealing to an anthropic argument that is known as the “fine-tuning” of physical constants and other cosmological parameters in the universe. This argument makes a link between the global physical conditions in the universe and the fact of existence of life on the earth. One of the simplest arguments that life could not exist in the universe’s past is that the universe was hot, which prevented the existence of such stable physical states as atoms. The stability of atoms is a fundamental condition for the existence of all possible biological forms of life. This stability is measured in physical terms by binding energy, which for an atom of hydrogen is determined as EH = ae2me2c2, where ae ≈ 1/137 is the constant of the electromagnetic interaction (the force which makes atoms stable), me is the mass of an electron, and c is the speed of light.432 It is known from atomic physics that in order to destroy atoms, it is enough to expose atoms to external electromagnetic radiation, that is, to highly energetic photons, whose energy is greater than EH. This implies that since all atomic structures are embedded in the external cosmological background, filled in, for example, with intergalactic gas (IGG) and microwave relict background radiation (MBR), the energy of particles in IGG and MBR must be less than EH.If we express this condition in terms of the effective temperature of particles and photons, using the connection between energy and temperature E = kT (k is Boltzmann’s constant), we can state that

TMBR [≈3K] < TIGG [≈100K] < TH [≈104K].

Through experimentation, it is clear that this inequality is satisfied at the current age of the universe. In the universe’s past, however, this inequality would not hold, because, for example, the TMBR is the function of the radius of the universe T ~ 1/a and it increases in the past when a → 0. At some point, TMBR exceeded TH and all atoms could not exist, so that no physico-biological form of life would be possible.

Certainly, this simple observation is true if we assume that the constant of electromagnetic interaction αe does not change in time, that is, that it is a genuine “constant.” It is interesting to find, however, that its particular numerical value is critical for the condition of the stability of atoms to hold. Indeed, if we change its value, for instance, if we decrease its value ten times αe* ≤ αe/10, then the corresponding temperature TH* = 10–2TH ≈100K will be comparable with TIGG and atoms can potentially be destroyed by interactions with the particles from IGG. In a similar way, if we decrease the same constant one hundred times, the corresponding temperature of atoms will be less than the temperature of MBR, so that atoms could not exist in the cosmological background at all. These simple arguments remind us again about the so-called fine-tuning of fundamental physical constants and external cosmological parameters, which provide the sustenance of life in the universe.

What is important for us, however, is that the brute fact of the observable values of the physical constants and cosmological parameters allows us to conclude that the conditions for life, understood in this context only in physical and biological terms, did not exist in the universe forever; that is, the universe was not always “anthropic.” On the contrary, one can conclude that it was “anti-anthropic.” One can object to this affirmation by saying that the universe is an evolutionary complex and that the emergence of life at a certain point of its evolution and in a given place was conditioned by the previous history of the universe; it is in this sense that one could assert that the universe was anthropic from the very beginning – that is, its initial conditions evolved later on, leading to a cosmic environment such that the necessary conditions of the emergence of life were fulfilled. The fact that we stress the word necessary (conditions for life) here reflects the weak point of any physical cosmology and even biology as being unable to reflect reasonably on the nature of the sufficient conditions for life to emerge in the universe.433

The difficulty that cosmology runs into if it attempts to justify the sufficient conditions for the emergence of life can be easily illustrated by referring to what is accepted by modern cosmology as fact that life (again understood in physical and biological terms), existing in the universe here and now, is destined to disappear from its surface because of either terrestrial physical or cosmological reasons. J. D. Barrow and F. J. Tipler provide a possible upper bound for the length of the existence of the earthly biosphere nearly equal to forty thousand years, which could support the evolution of the human species. This is a short future in terms of cosmological scales.434

In the astrophysical context, the upper bound on the existence of life on the earth follows from the finite age of existence of the sun (≈5 billion years from now), whose termination in an explosion will bring any life in the surrounding cosmos, including the earth, to extinction. Even if we disregard this local cosmic catastrophe and assume that humankind could spread beyond the solar system into outer cosmic space, we still have to face some global cosmological constraints on the duration of its existence, following from the theory: either the eventual collapse of the universe in the big crunch (the so-called closed universe) or the eternal frost of the ever-expanding (open) universe. In the former case, the termination of life is inevitable because the universe will heat up and prevent any possibility for life to survive. In the latter case, some cosmologists have tried to argue that there will be a possibility to extend the “existence” of “life” in the universe by abandoning the human body and adjusting the new form of life to an absolutely different environment. These hypotheses are based on the speculative assumption that life can be defined in terms of mechanisms producing information, so that the question of supporting life in the universe is a question of producing information with no ending. It is enough to remind us the long-standing paper of F. Dyson on life in the cold and dark future of the universe, in which he argued that civilizations can survive there by constantly reducing their rate of energy consumption and information processing.435 Dyson’s argument was that, despite these measures, the total amount of information produced in the universe may still be infinite, which would imply that the posthuman “civilization” could live forever in its subjective time.436

Despite the a priori speculative nature of this proposal, which is doubtful first of all on purely anthropological grounds, for it definitely departs far from what is usually understood by humanity as the existence in body and soul, the physics of Dyson’s model was revised recently with a very pessimistic conclusion that his scenario of existence forever is physically unachievable.437

It is now important to stress that all forecasts for the upper bound of duration of conscious life in the universe assume tacitly that humankind intends to continue to exist and does not participate actively in reducing its chances of survival, avoiding intentionally the situation on the terrestrial scale, which could be called a “doomsday syndrome.” The latter is usually associated with the global ecological crisis, nuclear holocaust, some lethal experiments with germ warfare, or experiments with high-energy physics that could lead to the destruction not only of our planet but of the whole universe.438 It is the possibility of the termination of the humankind-event by conscious beings themselves, when their activity threatens the natural roots of their existence, that points out that the sufficient conditions for the endurance of this event are partially rooted in the sphere of thought of these beings, in the realm of value and ethics, which is not rooted in nature but whose origin is the same as the human hypostasis itself, that is, in the realm of the divine goodness and wisdom.439

This brief reference to the future evolution of the universe and the conclusion about the inevitable termination of life in physical and biological terms leads us to the assertion that the universe is essentially (that is, in terms of its nature) “anti-anthropic” in the future, despite that its present state provides the necessary conditions for the existence of life. We can summarize our point in the following formula: The universe is anthropic now. It was anti-anthropic in the past, and it will be anti-anthropic in the future. This leads us naturally to the assumption that the phenomenon of life in the universe, considered at this stage only with respect to its grounds in physics and biology, is finite in regard to time and space. This is why we talk about the phenomenon of humanity as the humankind-event, that is, as a physical event whose spatial scale is finite and whose duration, despite being extended in time, is still finite and tiny (if seen from the present) with respect to the age of the universe. This event is not exactly what is usually meant by an event in the physics of relativity, in which an event is assumed to have no temporal extension – that is, it is treated as an instant, the set of which forms space-time. What is important in using the word event as applied to the phenomenon of humanity is that this event is not inherent in the cosmological background (there is no ultimate causal link between cosmology and anthropology); it depends on it – that is, the phenomenon of life is conditioned by physics – but only in terms of the necessary conditions. This means that in order for the humankind-event to happen – to become a part of history different from the dynamics of the cosmological background – there must be present some nonnatural factors making the event contingent on these factors. What are the factors? With no ambition of giving a final answer to this question, we will at least discuss this problem in the following sections.

The Humankind-Event and the Anthropic Principle

To elucidate the meaning of the humankind-event as contingent on nonnatural factors, in a cosmological context we should relate it to the series of ideas that are broadly called the anthropic cosmological principle (or AP).440 The AP has a variety of formulations, which can be found in Barrow and Tipler’s work The Anthropic Cosmological Principle.441 This section will discuss only the formulations known as the weak AP (WAP) and the strong AP (SAP).

The WAP concentrates on the privileged spatiotemporal location of intelligent observers in the evolutionary universe: they find themselves at a rather specific site and at a later stage of the history of the universe, for which the physical parameters that are treated as fundamental constants are not arbitrary but, rather, are fine-tuned with the conditions that enable carbon-based life forms to evolve.442 The WAP emphasizes that there are some necessary conditions that make it possible for life to emerge and to continue its existence in the universe. These conditions include, first of all, the size and the age of the universe: the universe must be old and large in order to create the conditions for carbon-based life-forms to emerge. If we translate this into the language of the previous section, the universe must be empty (that is, anti-anthropic) in its past in order to prepare the conditions for its anthropicity at present.

The positive feature of the WAP approach in cosmology is that it does not claim too much; in other words, it does not demand any inherent causality between the cosmological evolution and the emergence of life. It does not say anything about the laws of physics themselves or about the values of the fundamental physical constants, for example, about the actual value of the constant of electromagnetic interaction αe. It accepts these values as given and then attempts to explain some features of the universe. The WAP simply says that in order for the humankind-event to happen, some cosmological conditions must be fulfilled. The WAP does not link the phenomenon of humanity to the overall evolution of the universe, for example, to the initial conditions in the universe that would inevitably lead to the humankind-event.

In stressing the necessary conditions, the WAP does not, in fact, address the issue of what the actual cause of the humankind-event was. It is also clear that the WAP does not discuss the future of the universe; in other words, it leaves the question of the indefinite continuation of life out of its scope. It is also important to note that the WAP does not attempt to assert causality between the humankind-event and the structure of the whole cosmos, that is, to use the fact of the existence of life to predicate from it to certain special properties of the universe.

The question of whether the anthropic arguments provide some explanation in cosmology is still at the heart of scientific discussions. There have been some attempts to dismiss these arguments as physically explanatory by appealing to so-called string theory, which is not yet confirmed by experiments but which predicts specific values for the fundamental physical constants. If this prediction is correct and unique in its nature, the anthropic reasoning in physics becomes redundant; that is, the fact of the existence of intelligent life in cosmos cannot be used per se to argue from it to the structure of the universe.443 But the replacement of the anthropic argumentation by string theory, which consistently justifies the physics of the surrounding cosmos that permits life, does not mean that string theory removes the issue of the origin of conscious life in the universe. Even if this theory provides the explanation of the background that is necessary for the existence of life, it cannot address the issue of the sufficient conditions that actually made the potentiality of life become reality, to become the humankind-event.

One can reformulate the last thought by using more philosophico-theological terminology. From a wider system of thought, which is not restricted to the monistic vision of science, it becomes evident that cosmology and physics, although they try to put the conditions of the existence of humanity in a cosmological context, deal only with the natural dimension of the humankind-event, that is, with the existence of humans as physico-biological bodies. Physics itself can hardly speculate at present on the nature of human consciousness or the soul, and even less on the human composite hypostasis of body and soul.444 In other words, physics and cosmology can discuss the human phenomenon only from a perspective of its materiality, in terms of physics and biology, which can be communicated from one being to another and form a large uninatural population. The hypostatic, or personal, dimension of human existence is out of the scope of physics and biology. Certainly, the conscious nature of humans is tacitly present in all cosmological insights, because all are made by intelligent human beings, so that any claim about the universe has sense only in the context of the human intelligence in the cosmos. But cosmology has no key to the explanation of this intelligence itself. The intelligence is not obviously inherent in the cosmological observations and theories; it can be established only by metascientific introspection, not by physics itself.

One establishes, then, a correlation between the terminology used in cosmology and that used in theology. The necessary conditions for life to exist asserted in the WAP correspond in a theological frame of mind to the natural conditions for the existence of human persons. The WAP affirms the natural conditions for the humankind-event, but it does not relate to the issue why this event has happened, that is, why the existence of human beings understood as hypostatic creatures, as differentiated persons, became possible, why the humankind-event happened as hypostasized existence, not just as an element in the natural chain of impersonal and dispassionate interplay between chance and necessity. One sees, then, that the problem of the sufficient conditions for life to emerge and to continue to exist in the universe in cosmology correlates with the mystery of the personal, hypostatic existence of human beings in theology. We can anticipate, then, that the issue of the existence of life in the cosmological context cannot be fully addressed without an appeal to theology, for the insufficiency of cosmology to clarify the riddle of intelligent life in the universe points toward the grounds of life, which transcend the cosmological context, making the humankind-event relational (or contingent) upon nonnatural factors.

It follows from what we have just said that the issue of the necessary conditions for intelligent life in the universe must not be separated from the issue of the sufficient conditions. The AP is logically incomplete if it tries to affirm something about the structure of the universe relying only on the natural aspects of human existence. It follows, then, that the genuine anthropic principle must consist of both scientific and theological insights, which would open a route to the demonstration of the contingency of human existence in the universe and to a more intricate involvement of human beings in the communion with the grounds of the intelligibility of the universe.

It becomes clear that even the more speculative strong AP in cosmology does not reach its goal of proclaiming that the whole structure of the universe is to be subordinated to the fact of the existence of intelligent life in the universe: “The universe must have this properties which allow life to develop within it at some stage in its history.”445

An attempt that the SAP makes in subordinating the entire history of the universe to the requirement that life can emerge in this universe has a modest utility in cosmology.446 However, it raises some problems in a theological discourse. Indeed, if the SAP refers only to the natural aspects of human existence, then it obviously does not address the issue of sufficient conditions for the existence of life in the universe, for even if the universe is physically “designed” to contain biological life, it is still unknown what particular cause led ultimately to the emergence of biological organisms. The problem of consciousness in biological organisms is not even addressed by the SAP inference explicitly. There is some contingent element in the whole story of the appearance of life in the universe that is fundamentally unavoidable if one thinks about it in purely physical terms.

To illustrate this last thought, we employ a simple model of the emergence of complexity (which is often used to describe complicated living systems) in physics to show that it is always accompanied by a fundamental uncertainty, which cannot be resolved on a physical level but requires one to appeal to some transphysical (and nonpredictable) factors. Our example is based on two assumptions. The first is that the phenomenon of life, from a physico-biological point of view (we disregard conscious life in this example), is associated with the “manifestation of the attainment of a particular level of organised complexity in a physical system.”447 It is clear that this definition is an extreme form of reductionism, in which the whole spectrum of biological phenomena is treated from the point of view of physics. It is, however, sufficient for our present purposes to accept this model of living systems. The second assumption is that, for heuristic modeling (not a truly scientific one) of the emergence of the organized complexity, one can use any physical model of complex phenomena that involves an interplay of the necessary and sufficient conditions for the complexity to emerge.

Under these two assumptions, we intend to demonstrate that the emergence of “life,” understood simply as a definite level of complexity in a physical system, requires one not only to satisfy the necessary conditions, serving as a background for complex phenomena, but also to realize that a particular outcome of these phenomena (one that could be more precisely associated with the emergence of life) will be a priori unpredictable and contingent on factors that are not conceivable by the physics that operates with the given complex phenomena.

The simplest example of complexity in a physical system is known as the Bernard instability, which provides us with an example of chaotic behavior and emergence of complexity in the physical situation when we consider heat convection in the liquid contained between two planes with different temperatures and embedded in the external gravitational field.448 The meaning of the Bernard instability can be explained in simple terms as the transition from an initially uniform liquid to the state where this liquid becomes ordered in space, in terms of the Bernard cells, with a typical size of one-tenth of a centimeter, in which 1021 molecules experience a special type of correlation. The transition from the uniform liquid to the structured liquid can be compared to the transition from a physical state of the universe with no life to the state when life emerged. In the case of the Bernard phenomenon, the transition from the uniform state to the complex state depends on satisfying some conditions that can be called the necessary conditions. In particular, there must be two factors: (1) the presence of the external gravitational field and (2) the presence of the difference in temperature on the upper and low plains ΔΤ. When this difference reaches some critical level ΔΤc, one observes the transition from the uniform liquid to the liquid that is formed by cell tubes.

If we make an analogy between the external factors in the Bernard experiment (that is, the external gravitational field and the difference in temperature between the two planes containing the liquid) and the external cosmological conditions that are necessary for the emergence of life (such as the strength of the cosmological gravitational fields and the temperature of the background radiation, which decreases as the universe expands), then the necessary condition for the Bernard phenomenon to occur (ΔT > ΔTc) can be paralleled with some cosmological event, when the temperature of the background radiation dropped to such a level that the stability of the constituents of the biological factors on the earth were achieved and life could emerge.

The most intriguing part of the Bernard experiment, however, is that the phenomenon of complexity can be of two different types. The Bernard cell in a given place of the liquid can have either clockwise (right, or R) or counterclockwise (left, or L) chirality, so that the spatial structure of complexity, attained in a fixed point of the liquid, can be depicted as a sequel of cells with different order of chiralities, namely, either A (… RLRLRL…) or B (… LRLRLR…). It is important to realize that the complexity of the Bernard type will necessarily emerge if ΔT > ΔΤc, that is, the phenomenon is deterministic with respect to the external, necessary conditions. But it is practically impossible to predict what particular outcome – either A or B – will take place when the necessary conditions are satisfied. This means that if one repeats the experiment, leading to the Bernard instability many times, one can predict only the probability PA = 1/2 that there will be an outcome A and the probability PB = 1/2 that there will be an outcome B.

If we now make a hypothesis in our model, that the state A corresponds to such a level of complexity that leads to “life,” whereas the state B is “infertile,” then one can affirm that despite the deterministic external conditions (necessary conditions) for complexity to emerge, the actual happening in the system, leading either to “life” or to “no life,” is not in causal relation to the necessary conditions (for the actual happening is not conditioned by deterministic “law” but is the outcome of this law corresponding to a broken symmetry between A and B). It is probabilistic in nature and depends on factors that are not described by physical theory. What is the actual cause of a spontaneous choice between “life” and “no life” remains unclear. In other words, the sufficient conditions that led to the emergence of life are not explained. We observe here the display of the fundamental contingency in the physical system that demands for its explanation an appeal to factors that transcend physics.

Some authors, approaching the problem of chaos and organized complexity from a wide philosophical and theological perspective, invoke ideas about information, whose input could be a decisive factor in determining whether the complex state will be life-giving or not. J. Polkinghorne defends this idea in the context of chaos theory.449 Indeed, the information type of consideration is possible in the case of Bernard’s instability if we consider the experiment before and after the complex structure emerged. It is clear from what we have said before that the prior probability for the liquid to make a transition either to state A or to state B is the same and equals one-half. This means that the uncertainty in this system can be estimated in terms of the informational entropy I by the formula Ibefore = PAlnPA + PBlnPB = –ln2. There is, however, no uncertainty after the complexity has been established, for the outcome of the experiment is fixed and a posteriori probability for A and B is distributed either PA = 1, PB = 0 or PA = 0, PB = 1. In both cases, the informational entropy is zero: Iafier = 0. Then, in order for the system to “make a decision” as to what complex state to make a transition (that is, either to A or to B), the system needs to eliminate the informational uncertainty that equals ΔI = Iafter – Ibefore = ln2. This example thus provides some justification for invocating the idea of the active input of information in the chaotic systems in order to deal with an epistemological uncertainty.

What is, however, suspicious in such arguments is that this information is associated sometimes with a sort of divine agency. There are two major objections to this hypothesis. The first is physical and is based on the observation that, in order to overcome the informational uncertainty, one should use some sources of physical energy.450 The uncertainty in information is connected with the uncertainty in energy according to the second law of thermodynamics: ∆I ~ ∆E/T (where T is the temperature of the environment in which the system is embedded). This means that an active input of information needs to be supported by an input of energy from the physical world. In the case of Bernard’s instability, this source of energy is hidden in the difference of the temperature ∆T between two flat boundaries of the liquid, which means that an attempt to use the idea of information by contraposing it to physical agency is not justified. The second objection is theological in nature, for it questions whether the information – understood, for example, by Polkinghorne as the divine agency – is part of creation or not.451

The Orthodox appropriation of this proposal of Polkinghorne’s would be possible only if the notion of information were clearly defined in ontological terms. What is this information? If information is understood in the sense of “theory of information,” which is based on the laws of physics, it cannot be treated as an uncreated entity. In this case, it is probably better to refer to the information as some agent from the intelligible realm of the created world. Even in this case, the link between information and divine agency is still unclear, for the Divine is uncreated, whereas the intelligible information is created; since information is part of the creation and any talk about divine intervention (input) into physical process is theologically incorrect. The input of information from the “intelligible heaven” (treated as a noetic entity) can lead, however, to an outcome in a physical system that will have nothing to do with a divine purpose and will. The ontological difference (diaphora) in creation between the sensible and the intelligible (which is the constitutive element of the creatio ex nihilo) means that any influence (input of information) of the invisible upon the visible is possible only if it has been already encoded in the creatio ex nihilo itself; only in this sense can one claim the presence of the divine in their interaction.

It is more consistent, however, to look at the “causal joints” of matter and information from the perspective of the contingency rooted in the created world in both the visible and the invisible realms. This can take different forms, so that the divine action sought by an intellectual mind can be found encoded in the independence and freedom that the created world has received from God through the creatio ex nihilo.

When we observe chaos in the natural world and claim that it represents a kind of contingent order that is distinct from predictable aspects of nature, we contemplate, in theological terms, the difference between the logos of chaos and the logos of predictable and regular processes. The input of active information, to use Polkinghorne’s language, could only mean, from an Orthodox point of view, a qualitative change in contingent order that would probably have been caused by a “switching over” of the logoi responsible for these two types of processes. We cannot treat this “event” as an input of information because the logoi are preexistent in the divine Logos. Thus we are dealing here not with an active input of information (provided by God?) but with a change in the contingent order, which already has its own logos.

Finally, one can agree with J. Haught that information as such is a “mystery that science cannot comprehend through its atomizing reduction.452 Similarly to our pointing out that the origin of information lies in the uncreated logoi, Haught asserts that informational patterning is a metaphysical necessity for anything to exist, for it must have form, order, or pattern.453 In other words, the existence of a thing means that there is information about this thing; that is, its existence is the informed existence. But what does it mean? The informed existence assumes that there is the other, which is informed about the existence of some thing; this manifests the existence of this thing for the other and in the other. This can be rearticulated by saying that there is an inherent intelligible pattern of anything that is revealed through its relation to the other agency, who possesses the ability to enhypostasize this pattern as specific and concrete existence. Here we return to the issue of intelligible agencies in the universe, for only these, by sharing the intelligibility of the universal Logos, can reveal and operate with the information that enters scientific inquiry. It is only in this sense that information can be appropriated as a kind of divine agency, revealing itself through intelligible human beings, capable of grasping forms, orders, and patterns in the universe.

In concluding our discussion of a simple physical model of the emergence of complexity (which can be interpreted in a reductionist way as the emergence of life), we must rearticulate two important achievements: (1) the sufficient conditions for the actual emergence of life in the universe cannot be part of physical theory (this indicates the presence of a fundamental, unavoidable contingency in cosmological theory), and (2) the anthropic arguments deal only with the natural aspects of the humankind-event, whose actual happening is contingent upon some nonnatural grounds. This brings us finally to the understanding that the mystery of the humankind-event and the attempt of cosmology to inquire into it through anthropic arguments is linked with the mystery of the hypostatic existence of human beings; that is, their origin in the divine image and with the whole divine economy followed from the creatio ex nihilo. But the mystery of the creation out of nothing, as discussed in chapter 5, is theologically linked with God’s plan of the salvation of humankind. This means that the humankind-event, if seen not only from its natural (physico-biological) dimension but also philosophically and theologically, can be understood only through the chain of creation, incarnation, and resurrection.

The strong AP, then, can be reinterpreted, not so much physically but theologically. The status of this interpretation will be, in the parlance of J. Leslie, as a logical explanation of the link between the humankind-event and the structure of the universe, rather than a causal explanation in physical terms of how the presence of human life in the universe cascades up and down to physics in order to explain its laws and their particular outcomes leading to the existence of life.454

This means that the causation that is effectively present in the universe, starting from its creation and up to the point when human life emerges, is subordinated not only to the logic of physics but also to the logic of the divine plan to create such a universe in which human beings, being in God’s image, could live and could learn the truth about God and themselves, in particular, that they are not only natural creatures but also hypostatic and ecclesial beings who can enlighten and personify the universe through their presence. It is these human beings who can follow the way of deviation from the necessity of nature in order to transfigure its own cosmological roots according to their ultimate ecclesial aim to achieve the union with God.

It is clear, then, that the theological link between the universe and the humankind-event is not entirely natural. When we talk about the divine plan of salvation of humankind, we assume that this plan is to be incarnate in the realm of contingent creation. This makes it legitimate to assert that since, in the divine reason, the creation of the world out of nothing is linked to the fact of the salvation of humankind, there must be some display of the connection between the world and humanity that is encoded in the theology of creation. In a sophisticated way, this link can be revealed by reasoning we have used several times in this book, namely, by referring the display of the universe and the presence of human beings in it to their common ground in their otherness, that is, in the transcendent God-Creator. Theologically speaking, the existence of a link between the world and humans is inevitable. The major problem, then, is to articulate this link not only in natural terms, for it cannot be fully expressed from within its worldly manifestations. Otherwise, it would mean expressing in worldly terms the contingency of creation, which cannot be done.455 The challenge to science is to detect the presence of this contingency in scientific theories with no full explanation of its origin; the latter is exactly what theological methodology can offer.

Cosmology taken in its purely scientific realization can pretend to reveal the fundamental contingency of human existence in its natural dimension on some specific conditions that have been realized in the universe. It will be, however, extremely difficult for cosmology alone (that is, with no support from philosophy and theology) to reveal the ground of the universe and of human beings in it beyond the universe in the realm of the uncreated (we have already seen examples of the theological reasoning on the issue of creation in cosmology and the origin of temporal irreversibility in the universe in chapters 5 and 6 that point toward the transcendent grounds of existence). But this means precisely that cosmology should look for the presence of contingent necessity in its laws and facts about the existence of human beings in the universe (that is, the necessity that by its display in the universe never acquires the features of sufficiency), for the sufficiency, if it were to be possible to reveal it in the display of the universe, by its logical constitution, would be an ultimate ground of contingent necessity in the world, which would correspond to the hidden knowledge of the divine plan of creation and salvation.

If we now look more closely at the affirmation of the SAP – that the universe must have some properties in order to allow human life to develop in the universe – and if we treat this idea theologically, we can see the referral to the creation of the universe with the purpose of the salvation of human beings as creatures with a particular anthropological constitution. For human beings to be made in a particular hypostasis (that is, to be a unity of a body and a soul), there must be conditions for the natural aspects of the human hypostasis to be realized, namely, conditions for the existence of the human body, which is made from the same material available in the universe. The SAP, treated from this perspective, provides in its above form a theological affirmation of the design in the universe in order to fit the human body. But the SAP, as we have established before, deals only with the natural aspects of the humankind-event; that is, it does not address the origin and existence of the human hypostasis as the union between the bodily functions and the abilities to think and contemplate things and ideas as well as to integrate them in a single consciousness. It is exactly at this point that the analysis of the SAP reveals the presence of fundamental contingency, as an inability to provide any inference on the mystery of the hypostatic dimension of human existence.

It must be also noted that the SAP does not address the future of human life in the universe; it does not treat the phenomenon of man as an event. An event means not just a happening in the chain of causal physical factors; rather, it is by itself a constitutive element for physical reality, something that makes the undifferentiated matter “the reality.” Thus an event itself is a hypostatic notion, which is called to constitute the elements of nature in space and time. Any event by definition is contingent upon some agency that is not entirely rooted in the natural. An event has a beginning and an end. Similarly, the humankind-event has a beginning and an end. This implies that what the SAP asserts is that at some stage of the evolution of the universe, there must be necessary conditions for the humankind-event to happen. This means that the evolution of the universe is constructive from the point of view of the history of salvation only up to the humankind-event. This implies in turn that the link the SAP attempts to make between the whole evolution of the universe and the humankind-event is actually subordinated to the latter; yes, the universe must evolve in order to allow the humankind-event to happen, but the future evolution of the universe is not subordinated anymore to the humankind-event, which, according to modern physics and theological eschatology, is finite in time. This implies that the most that the SAP can say about the structure of the universe (in terms of the humankind-event) is to affirm something about its past as contingent on the present, not the future.456 The final AP of F. Tipler, which attempts to extend the assertion of the SAP to the indefinite future, does not seem to be a plausible version of things in the context of the notion of the humankind-event. The critique of this principle will be touched on briefly later in this chapter.

One can conclude thus that the phenomenon of man in the universe, analyzed in the context of the anthropic arguments in cosmology, is in its essence finite and contingent on nonnatural factors, which can be elucidated only by appeal to the theology of creation. Being an element of creation, the phenomenon of humanity acquires the features of an event. It is in this sense that all assertions of the WAP and SAP can be interpreted as indications of the fundamental contingency present in cosmological theories, open to further explanation and based on nonphysical assumptions.

Hypostatic Dimension of the Humankind-Event

This section articulates in detail what is meant by the hypostatic dimension of the humankind-event. To do this, we start with elucidating the role of human hypostasis in the process of knowing the universe. It can sound tautologous that the very fact that physics can speculate about the universe and the place of humankind in it is based on the ability of humans to contemplate the universe and form a coherent picture of the world. This ability is associated with the intelligence that makes human beings fundamentally different from other forms of biological life. This fact, despite being tacitly present in the very foundation of science, and in cosmology in particular, is disregarded as constitutive for modern knowledge. Human beings as intelligent observers and conscious agencies in the universe are downgraded to the level of passive observers, so that the presupposition of the observations themselves (that is, human consciousness) is excluded from the subject matter of physics. B. Carr stated this situation in physics and cosmology, treated as man’s model of the world in which he lives, by saying: “Yet one feature which is noticeably absent from this model is the creator, man himself. That physics has little to say about the place of man in the universe is perhaps not surprising when one considers the fact that most physicists probably regard man, and more generally consciousness, as being entirely irrelevant to the functioning of the universe. He is seen as no more than a passive observer, with the laws of Nature, which he assiduously attempts to unravel, operating everywhere and for all time, independent of whether or not man witness them.”457 The fact that such a vision of humans’ place in the universe is fundamentally incomplete can be easily elucidated by a simple example.458

Let us analyze a typical diagram from popular scientific books that depicts different objects in the universe, starting from atoms and finishing with galaxies, in terms of their spatial sizes or their masses.459 The position of human beings in this diagram is seen as mediocre: its typical spatial size is 1012 times higher than the atomic one, and the place they occupy in space is 10–19 times less than the size of the visible universe. Despite that the existence of human beings depends on atoms and the size (or age) of the universe (this is a typical anthropic line of reasoning), if it is seen from a purely physical point of view, the position of human beings in the universe is insignificant. For every contemplative and psychologically oriented thinker, the internal inconsistency of a purely physical view is hidden in the fact that human reason, which is not present in the diagram explicitly, is encoded in it implicitly, for all objects starting from atoms and finishing with the universe as a whole are integrated in a single logical chain, which is possible only because the human insight is present everywhere. Thus all objects in the chain of physical being are united by human reason in a single consciousness of the whole that is sustained from the “vertical” dimension of human intellect, which is linked to the natural conditions of human existence but at the same time transcends this existence, revealing itself as dependent not only on physico-cosmological factors but also on nonnatural or, as we call them, hypostatic factors.460 This idea is illustrated by the diagram in figure 7.2, which presents the position of humans in being in terms of two dimensions, natural and hypostatic.

One could object to our use of term hypostatic by pointing out that what we mean by it is human intelligence,which assumes the ability to contemplate objects in nature, form their meaning, and communicate this meaning to the whole humankind. Some would say that all these functions of human intellect have naturally emerged, so that they constitute a part of nature, although quite different from what one means by physical nature.461

(Spatial scale)

Atoms Human being as Natural

10–10cm 102cm physical substance 1028cm Dimension

Figure 7.2

In this case, one could say that, instead of naming the vertical dimension hypostatic, it would be easy to call it an intellectual (or psychological) dimension and not to make a sharp difference between horizontal and vertical dimensions in figure 7.2. Our response to this objection would be that the presence of intellect and consciousness, even if they are treated in a reductionist way as epiphenomena of physical and biological function, do not explain and justify the aspect of personhood in human existence, that is, genuinely human hypostasis as personified existence of human beings in different bodies. The personhood of human beings implies not only that they have self-consciousness (that is, the perception of one’s own ego), but also that there is a fundamental distinction from and, at the same time, relatedness to other existences, or other hypostases.462 The personhood as hypostatic existence means that it cannot be communicated to another person (in contrast with the natural, for example, biological factors, which are shared by all human beings and can in principle be communicated from one human being to another, such as the transplantation of organs). Every particular existence is unique and inexpressible in terms of the other. Despite the fact that the hypostatic unity of the human composite of body and soul cannot be communicated in a physical or biological sense, the hypostasis of the human person is formed only through its relation to other hypostases (that does not necessarily imply interaction on the level of substance) and to the common source of their origination.463 In other words, the nonnatural aspect of the hypostatic dimension in human beings points toward the fundamentally relational essence of this existential dimension. This literally means that the symbol of human being in figure 7.2 as hypostatic (large and gray) stands for the whole of mankind (in contrast to natural man, small and black) as the community of beings with a common principle (logos) of human nature related to God and realized in different hypostases (different persons).464

One can say that the integral knowledge of the universe contains in itself an implicit premise that there is a “way” of communication with the universe that would allow human reason to find truth about the universe and to share this truth among the members of the whole community. But the establishment of the “meaning” of what is contemplated by the members of the community presupposes that there is a common ground of sense and intelligibility, which is shared not only naturally (that is, biologically, on the level of the corporeal) but also hypostatically (that is, it is not deduced from nature through a chain of physico-biological and physiological causations), the very possibility of which is rooted in their common relationship to the common source of existence in creation, to the Logos in whom the whole universe and human persons are inherent hypostatically.

Since all things in creation can be treated as effected words of God, knowledge of these things implies the ability to “hear” the words of God, not simply through natural faculties of the body (which provide only the outward impression) but through immediate participation in these words, which takes place on a nonnatural level. The fact that human reason can penetrate space and time and contemplate in different symbols things invisible and nonobservable, microparticles and cosmological structures, points toward man’s ability to transcend empirical nature to the realm of intelligible forms. At this point, the importance of the hypostatic dimension for understanding humanity’s place in the universe becomes clear. It is because of the hypostatic unity of the body and soul, which forms the logos of man and originates from the divine Logos, that it is possible to argue together with Maximus the Confessor and other Patristic writers that man, in a way, imitates in his composition the whole universe, empirical (that is, explicitly visible) and intelligible (invisible); that is, it manifests itself in the basic diaphora in creation that points to the logos, which holds different parts of creation together.

Maximus developed an allegorical interpretation of the universe as man, and conversely, of man as microcosm and mediator between the parts of the universe and between the universe and God.465 Maximus articulates the similarity between the composition of human beings and the composition of the universe from the point of view of the hypostatic unity of different parts in them. A passage from Maximus’s The Church’s Mystagogy (chapter 7) elucidates the meaning of this similarity:

Intelligible things display the meaning of the soul as the soul does that of intelligible things, and… sensible things display the place of body as the body does that of sensible things. And… intelligible things are the soul of sensible things, and sensible things are the body of intelligible things;… as the soul is in the body so is the intelligible in the world of sense, that the sensible is sustained by the intelligible as the body is sustained by the soul;… both make up one world as body and soul make up one man, neither of these elements joined to the other in unity denies or displaces the other according to the law of the one [the Creator] who has bound them together. In conformity with this law there is engendered the principle [logos] of the unifying force which does not permit that the [hypostatic] identity unifying these things be ignored because of their difference in nature.466

In a scientifico-cosmological context, this text can be interpreted as an insight that can lead a cosmologist beyond the sphere of the visible universe (which is accessible to the senses) to that which is invisible and described in terms of mathematical objects (which human reason, being an analytical part of the soul, operates with because the reason is indwelling in the body), so that through the visible universe the reason reaches the intelligible universe, which also indwells in the visible despite being different from it. It is because of the hypostatic unity of the body and soul in a cosmologist that one can reveal the hypostatic unity of the visible and intelligible universe. A cosmologist relates opposite phenomena: small (atoms) and large (galaxies), visible present cosmos and its invisible past; cosmos as multiplicity of different visible facts (stars, galaxies, distribution of clusters of galaxies) and the mathematical cosmos (as uniform and isotropic space).

The human ability to recapitulate in its knowledge all constituents of the universe, and to recognize that human being is deeply dependent on the structural and nomistic aspects of the microworld as well as of the megacosmos, makes the position of humans in the universe exceptional and unique. The recapitulation of the universe in man takes place not only on the natural level (which is affirmed in the anthropic arguments) but, and this is much more nontrivial, on the hypostatic level; this implies indirectly that human beings are participating in outward hypostasization of their own existence by revealing the meaning of various levels of the universe. The latter is possible because human beings can use their own hypostasis to bring the undifferentiated existents in the universe to their proper, personal existing, that is, as the existence through the apprehension in the persons. Such an existence of the universe through the transferral to it of the personal dimension of humankind can be described in theological terms as the enhypostasization of the universe. In different words, human persons, or humankind in general, despite being physically located in one particular point of the universe, share through the fusion of knowledge their existence with all other places and ages of the universe. It is this existence of the universe in the other, that is, in human beings, that means that the universe is enhypostasized by human beings. One can affirm at last that the humankind-event, being made hypostatically inherent in the Logos, is itself the source of further expansion of the hypostatic inherence toward the universe, which has the form of a revelation of the intelligibility of the universe, its purpose and end through the human personhood.467

The place of humankind in the universe can be expressed by using the old idea of microcosm, as the world in the small. It is clear, from what we have discussed above, however, that the major feature that puts humans in the “central” position in the universe is the fact that the reality of this universe is articulated by humankind; that is, the universe is revealed to itself in the hypostasis of human being. This adds to the man as microcosm the title of mediator, for it is man who establishes the link between the universe and God, not naturally or physically, but hypostatically; that is, the universe as the part of creation is offered to God in the hypostasis of humankind through its thanksgiving wonder of the good creation and its “cosmic liturgy” of knowledge, which, being an open-ended advance of human intelligence, also changes (transfigures) the universe.

The fundamental problem, however, in asserting that the universe is made hypostatically inherent in human apprehension, and that the universe appears to us as intelligible reality, is rooted in the origin of the intelligence of human beings and its relation to the intelligibility of the universe, which is discovered through the scientific quest. It follows from what we have said before that the root of human intelligence lies in the hypostatic dimension of human existence, which can be expressed in such words as the relation to the ultimate source of intelligibility, which is beyond the world. We also stressed that the analogy between human being and the universe, which is expressed in terms of the commonality of their logoi, points to the fact that there is contingent intelligibility in the world that is ultimately of the same origin as intelligence in humans. This leads us to the conclusion that the act of making the universe hypostatically inherent in human apprehension means, in fact, recovering the contingent intelligibility of the cosmos (which is not contemplated by the cosmos itself) through the human hypostasis. It is clear, then, that for this to be possible, one should assume that human intelligence is somehow tuned with the intelligibility of the universe. This leads us back to the idea that the intelligence of human beings, rooted in their hypostases, and the intelligibility of the universe, which is not self-evident and which is revealed to human beings when the universe is apprehended and articulated by them, have a common root, one beyond creation and hidden in the Logos of God.

The central position of humankind in the universe can now be described in a different formula by saying that man is positioned between God and the universe in the following sense: human beings are made inherent in the hypostasis of the Logos of God as the accomplished hypostases, whereas the other objects in the universe are made inherent in the Logos without having their own hypostases, so that their existence is not personal and as such is devoid of the realization of purpose and end. It is only through the hypostatic inherence of these objects through human apprehension that they are brought to a realization of their function in the divine plan, when the objects themselves receive their meaning in terms of purposes and ends.

We now have come to the central question in our discussion of the place of man in the universe: Why is the hypostasis of human beings an accomplished one, so that they can mediate between personal God and impersonal nature, or, in other words, Why do human beings exhibit such existences in the universe that resemble the image of the Divine and, at the same time, recapitulate in themselves the whole universe? Repeating the same question in different terms: Why does the humankind-event take place in the universe? We do not expect to reveal the answer in a form like “God created the universe and human beings in it because of this and this.” By posing this question, we simply want to express our main concern and argument that the mystery of the phenomenon of humanity in the universe can only be uncovered partially by the sciences in terms of the natural conditions suitable for the existence of life; the genuine problem of the humankind-event still remains a philosophical and theological issue, in which other (nonscientific) sources of human experience must be invoked. This points precisely to the fact that the human hypostasis is capable of insights and intuitions that are not accessible to discursive thinking.

The question posed above is not scientific in origin. However, it follows logically from what we have discussed in a scientific context. This implies that a response to the question on the position of human beings in the universe will finally be theological in nature, based on the understanding as well as the direct experience of the cosmic meaning of the incarnation of the Logos of God and of the Christ-event. Before we turn to this issue, which is central for this chapter, it is important from a methodological point of view to rearticulate the meaning of the enhypostasization of the universe in the human hypostasis in rather contemporary terms, which are closer to present-day scientific discourse and its dialogue with science.

We leave out for a while the question of the origin of the human hypostasis, assuming that it is somehow in place and that it initiates cognitive faculties in human beings. If describing these faculties empirically, or even philosophically, one can ask what it means that the universe is brought into being (that is, enhypostasized) or selected by observations. In other words, what are the epistemological consequences of our ability to know anything about the universe and how is this reflected in modern discussions about the status of cosmological knowledge as being anthropic by definition? These issues can be illustrated by examples from the concept of the anthropic principle considered in its epistemological dimension.

From Anthropic Transcendentalism to Christian Platonism

Anthropic Inference in Cosmology and Epistemology

The presence of the hypostatic dimension in the humankind-event can be illustrated through analysis of the AP from an epistemological point of view. It sounds nearly tautological that the fact that we observe the universe as it appears to us is deeply embedded in the nature of our cognitive faculties. In other words, we can observe only things in the universe that can enter into the process of our cognition. We cannot observe those “realities” that cannot cause in human being any cognitive or emotional response. This leads us to the simple observation that the visible universe is, in a strange way, selected by acts of human cognition.

This conclusion is not new at all, for in science, especially in the experimental sciences, it was recognized long ago that the instruments and experimental arrangements affect the results of observations and constrain the structure of the sought-for realities. Quantum mechanics, in its Copenhagen interpretation, for example, asserts explicitly that the phenomenon becomes an element of reality only if it is registered, that is, observed and measured.468 This means that the notion of reality as it is in itself has no sense in such a context. In astronomy, for example, our knowledge of the objects in the universe is predetermined by our ability to see or detect different types of radiation that comes from the cosmos – for example, electromagnetic radiation can be detected by optical telescopes or radio telescopes; gamma rays need a different type of equipment sensitive to them; cosmic rays can be detected by special tracking devices; gravitational waves are expected to be measured by either solid-state antennas or laser-interferometers. The visible universe, as we define it through all different observations, is thus deeply connected with the nature of our cognitive faculties extended by apparata. This reflects the well-known philosophical view that reality can be defined only within a subject-object relation.

It is enough to recall the Kantian treatment of experience as bounded by two forms of sensibility and twelve categories of understanding. It is within this experience that we can know nature and can claim that our knowledge is objective. We can rephrase this by saying that there is an epistemological horizon in the advance of knowledge that is circumscribed by our cognitive faculties. This implies that what we know is, by definition, the world of phenomena, which is self-selected because of our faculties. This line of thought can lead naturally to a claim that the AP is an epistemological tautology, namely, that the visible universe, which is fine-tuned to sustain the life of human beings, is what is called in Kantian terms the phenomenal world, so that it must by its constitution include observers who perceive this world through the “prism” of their cognitive capacities. The question of how particularly the Kantian epistemology can cascade down into the methodology of scientific research was discussed in a paper by W. I. McLaughlin, who tried, for example, to make a link between the number of observed astronomical phenomena and the possible information that can be obtained in principle in this subject area because of the limited number of categories of the understanding.469 In McLaughlin’s approach, the AP is trivial because we can see the world only from within the horizon circumscribed by our faculties, so that what we see is immanent to what we have at our disposal.

Kantian philosophy, however, does not provide any explanation of why we have the cognitive faculties we have and what is the ultimate source of them and, as a consequence, of the structure of the universe we observe. Kant’s invocation of the idea of the “noumenal world” (things-in-themselves) was just a way of referring to something that is beyond the world of phenomena but which, being completely inaccessible to us, functions as an empty logical form, playing the role of a delimiter that outlines the boundaries of our knowledge, which separates being from nonbeing. It is important to realize, however, that to affirm that the world of phenomena is self-selected by our cognitive faculties, one should assume, at least in pure thought, that this world is hypostasized in its concreteness with respect to something that transcends it and that is not the world. This assumption, according to Kant, leads to antinomies of the reason that warn that the transcendence of the understanding beyond the world of phenomena is an illegitimate procedure. The paradox here is that, in order to affirm the concreteness of this world, one has to assume that there is nonbeing of this concreteness that cannot be grasped within the human cognitive faculties. According to Kant, transcendence of the world of phenomena was a break beyond the realm that is formed through the relation between subject and object, whereas Kant’s follower J. G. Fichte treated this not as a break beyond the subject-object relation but, rather, as the hypostasization of the abstract transcendent realm by the reason within its purely subjective capacity. This means that if, for Kant, the existence of the world of noumena was problematic by its definition, for Fichte, its existence was immanent with the existence of thought itself, which produced this notion.

If we apply this philosophy to the AP, we must admit that the AP functions in modern cosmology as the principle that sets the boundaries to our own knowledge of the visible universe. In other words, any cosmological theory that pretends to describe adequately the visible cosmos should satisfy all the constraints imposed by the strong AP. It does not mean that the AP, as a sheer metascientific statement, explains why the universe is as it is but that the AP acts as the inference that affirms in physico-mathematical terms the concreteness of the visible universe. The novelty of the AP in formulating the specificity of the subject-object relation in cosmology, however, has a profound significance that had not been recognized before this principle was established – namely, it articulates the concreteness of the world, expressed in terms of the fine-tuning of physical and cosmological constants, in terms of its stability. This means that the being of the universe where we live is not an obvious thing, for it is fundamentally unstable with respect to imaginary changes of physical parameters. Stability in this sense is associated with the existence of the visible universe and of human life in it, whereas instability of the universe with respect to small changes of physical constants implies that there is nonexistence of life in all other “imaginary” universes with different sets of fundamental parameters. This fact rearticulates the epistemological dimension of the AP, namely, that in order to assert the concreteness of the visible universe in terms of its adjustment to the cognitive faculties of the observers, one should assume that it is contraposed to its own otherness, that is, to such a state of affairs that excludes life and observers and that can be called the noumenal world in Kantian terms or as a different universe in physical terms. This comparison of the noumenal world with the different universes has a limited validity, for in the Kantian context, the noumenal world is not part of any experience, including the experience of abstract mathematical creativity. It is, however, possible to argue that the concept of different universes, which is invoked in a modified version of the strong AP, functions in cosmology as a “model” of thing-in- itself. These fine distinctions in the pursuit of the idea of transcendence in cosmology are not important in the context of this research, however, for we have already established the vision of the Kantian transcendental method through the eyes of Christian Platonism.

It is evident from what we have said above why the further development of the strong AP led to its reformulation in terms of the ensemble of the universes. Indeed, if the SAP is treated as a principle of self-selection of the visible universe, then to make such a global selection legitimate, there should be that from which to select; otherwise, no justified explanation of the fine-tuning of the universe in ontological terms can be established. Indeed, while the strong AP “explains” why we do not observe universal characteristics incompatible with our existence, it does not explain why the observable characteristics of the universe, evidently compatible with our existence, take place at all. This is why, for a full-value strong anthropic explanation, certain additional assumptions are needed. These are provided by a world ensemble hypothesis, the indispensable part of the strong anthropic inference.

The Many-World Hypothesis and Its Theological Interpretation

The concept of many worlds sounds extremely exotic and nonscientific because it postulates something well beyond the boundaries of what is scientifically “known or knowable” at this time.470 There is, however, a popular belief among some physicists and philosophers that it can be given some physically realistic meaning based on certain present-day cosmological ideas that depict the universe as a whole as consisting of many physically disjoint domains governed by different laws of their “physics.”471 From this point of view, all possible “physical” arrangements can be realized in small universes comprising the ensemble. At least some universes will, in this case, be suitable for life and intelligence. Further, to explain why we find ourselves in such a well-designed universe – with its specific laws of nature, initial conditions, spatial topology, and so forth – we have to apply the strong AP, which makes our existence impossible in any of the universes that are designed in a different fashion, with no pattern for the fine-tuning necessary for the existence of human beings.

If, then, one assumes in a physically realistic sense that the ontological existence of the ensemble of universes is of the same quality as the visible anthropic universe, then the modified statement of the strong AP (MW-SAP) that “an ensemble of other different universes is necessary for the existence of our Universe” must be critically appraised, for it pretends to be a scientific statement that is subject to verification or falsification on purely scientific grounds.472 Since this justification is quite problematic, it would be more reasonable to treat this statement not as empirical but as theoretical, that is, mathematical. This implies that it must have, instead, the form of a theorem. The MW-SAP theorem can be formulated in this way: an ensemble of universes as a part of our world must exist (its existence is necessary and sufficient) for our universe to exist. For our universe to be chosen from something, it is necessary for the ensemble of universes to exist. If the ensemble of universes does exist, it is sufficient for our universe to exist, since the plurality does always contain all kinds of universes, including the one where we live. To attempt a proof of this theorem, there must be established a priori a concept of many universes, which can be done only with a great extent of metaphysical speculation.473

The metaphysical concept of the world ensemble refers back to the block of ideas associated with the long-standing concept of plurality of worlds but renewed by ideas either from the many-worlds interpretation (MWI) of quantum mechanics or from chaotic inflationary cosmology (as well as from the old model of the oscillating universe). Probably the best way to give an idea of this model is to quote one of its authors: “The universe is constantly splitting into a stupendous numbers of branches, all resulting from the measurement-like interactions between its myriads of components. Moreover, every quantum transition taking place on every star, in every galaxy, in every remote corner of the universe is splitting our local world on earth into myriads of copies of itself.”474