4. Technique

Technique

When one thinks of the term ‘icon’, what usually comes to mind is a religious painting on wood. But in fact icons are made of many different materials. From the early period in particular we find icons of ivory, gold, enamel, mosaic or marble. Icons made of cloth – woven and embroidered – also survive. And small metal icons (mostly cast in bronze or brass) were particularly popular in Russia in the 18th and 19th centuries.

Most icons painted on wood are executed in egg tempera, where egg yolk is the binding agent for the pigments. An alternative, encaustic, technique, whereby paint was burned into heated wax, fell into disuse after the Iconoclasm.

Materials

An icon painter would start by looking for a wooden panel, preferably one free of resin (lime, beech, cypress or cedar, for instance). He would then cut it to the right size: for a large icon, several planks may have had to be glued together. Sometimes he would make a groove in the wood with a chisel (kovcjek), leaving a broad, raised edge (polje) to serve as a frame.

To prevent the panel warping, battens were then fixed to the back of the panel. In Russia, the battens (sponki) were slotted into grooves carved for this purpose. From the 18th century onwards, this was also sometimes done in the lower and the upper sides of the panel. In Greece, the battens were fastened directly onto the back, using nails or wooden pins. The painter would then often roughen the front surface and glue a piece of linen (povoloka) or rough paper on it. The next step was to apply a paste (levkas) consisting of chalk (such as ground marble, or perhaps alabaster) and various binding agents. Many layers of this paste were applied (15–20 was not unusual). They were repeatedly rubbed and polished to create an extremely smooth surface.

On this shiny white background, the painter then drew or scratched the outlines of his picture. He would be following an old icon or using a design from a book of examples. Often he knew his subject matter so well that he could draw it from memory. He would then cover the background with gold leaf (or sometimes silver leaf). Now he could start the actual painting, using egg tempera. The colours were made from organic materials or finely ground minerals. Holy relics were also sometimes mixed in with the paint. The artist painted in layers, from dark to light, finally adding some light effects and perhaps some gold embellishment.

23. St Mark the Evangelist, Russia, early 17th century, 49 · 39 cm, Zoetmulder icon collection

24. Mother of God of Vladimir (Vladimirskaya), Russia, early 18th century, with silver oklad with river pearls and glass, dated 1828, 31 · 26 cm, Zoetmulder icon collection; detail p. 47

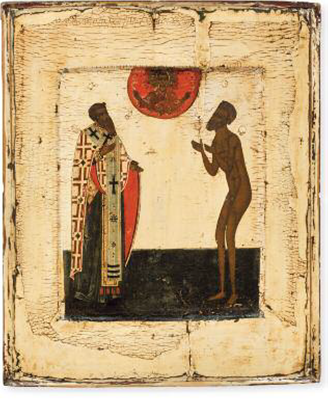

25. St Basil the Great and St Basil the Hermit, 16th century, with gilded silver oklad with cloisonné enamel, dated 1876, Moscow, 31.7 · 26.3 cm, Zoetmulder icon collection

26. Detail of figure 52, 21 and 61

The painting was then varnished with a varnish (known as olifa) made of linseed oil and resin. This gave the colours a deep shine. However, it had the disadvantage that it darkened quickly as it attracted the soot from candles and incense. This explains the existence of Black Madonnas, icons in which the Mother of God has a dark face. This was merely due to the accumulation of soot and grime.

In accordance with the rules of the Church, the painter also added the sign or name of the person or scene shown in the icon. The Greek monograms were used for Christ and the Mother of God. In the case of Russian icons, Old Church Slavonic was used. [26] This is a South Slavic dialect, into which St Cyril translated the Bible. As a final action, the finished icon was consecrated in the church.

27. The Dormition of the Mother of God, Russia, 19th century, 28.2 · 24 cm, metal icon, Zoetmulder icon collection

Stylistic elements

When we look at an icon today, what we are struck by are the strange buildings, the distorted mountains, the unnatural faces and the schematic figures. But these do not stem from any lack of skill on the part of the artist. They are explicitly part of the painter’s artistic language. The goal of the icon painters was to give visible form to an invisible reality. To achieve this, they used a reversed perspective, whereby the vanishing point lies not in the icon but with the viewer. The viewer becomes, as it were, drawn into the icon. [23]

What we also notice is the extensive use of gold leaf. The golden background means there is no horizon, no sky or landscape. Saints in icons have a gilded halo, and their clothing is also embellished with gold. This emphasises the spiritual dimension. In addition, the representation on the icon remains flat and two-dimensional because no shadows are shown.

Metal revetments

Icons were often partly covered in silver, a custom that goes back to the Byzantine period. They might be given a silver edge (basma) or a silver background (oklad). Alternatively, the whole icon might be covered in silver, with only the face and the hands visible (riza). The Russian word oklad means ‘cladding’ or ‘clothing’, while riza means ‘jacket’: these terms are used indiscriminately.

Such coverings, or revetments, were originally provided as an act of gratitude. If an icon had worked a miracle, for instance, the beneficiary would commission a silversmith to make a ceremonial cover for the icon. [24–25]

Riza and oklad icons became increasingly popular from the 17th century on, reaching a highpoint in the 19th century. Well-known goldsmiths and silversmiths, such as Fabergé and Ovchinnikov, created gold and silver revetments that were veritable works of art, sometimes adorned with enamel and precious stones. The popularity of these sorts of icons, however, led to a decline in interest in the painting itself. Simple riza and oklad icons were produced, in which only the visible parts (the hands and the face) were painted. The rest of the panel, which would be covered up, was left bare.

Metal icons

Thanks to their indestructibility and often small format, metal icons could be worn around the neck and were ideal for travellers. Metal icons were also used in the home and in churches, and they were often fastened to the wooden crosses on graves.

The first metal icons date from the 11th century, but it was not until the 18th and 19th centuries that they became popular. [27] This was probably mainly thanks to the Old Believers, who strongly opposed the reforms of Nikon, the Patriarch of Moscow, and split off from the Church in the mid-17th century. Setting themselves up as defenders of the old traditions, they established not only special workshops for painted icons, but also started producing metal icons. The main centre for casting these icons was the monastery at Vygorezki, which the Old Believers had set up in 1695 on the banks of the River Vyg, in the North, near the White Sea. Smaller workshops were also set up throughout the country, including in Siberia.