Part II. The unfolding revelation of the Tao in human history

THE SEAL: «Shang Ti», the oldest Chinese name for God, found in the earliest extant writings which emerge from Chinese prehistory, ca. 2300 B.C.

Overleaf: Ch’ien Hsüan (ca. A.D. 1235–1305), Pear Blossoms.

Chapter One: Departure from the Way

1. Pristine Simplicity

In the beginning, man was created in a state of pristine simplicity, pure awareness. His thoughts and memories were not diversified and fragmented as they are today, but were simple and one-pointed.409 He knew no mental distraction. While being wiser than any human being today, he was in a state of innocence, like a child, and in this state he lived in deep personal communion with God the Tao/Logos and with the rest of creation, holding spiritual converse with them.

Being in such close communion with God, primordial man participated directly in God's Uncreated Energy, which he experienced as a Divine and ineffable Light which flooded his whole being. He was as it were clothed in this Light.410

Primordial man possessed self-awareness; that is, he was aware of an «I», of being a unique creation, endowed with freedom of will. «Made in the image of God»,411he had an immortal spirit that could draw eternally closer to his Creator. All of this gave him his special sense of personhood.

Unlike the people of today, however, he did not have a sense of individuality. By this we mean that he did not live under the illusion that, as a unique person, he was sufficient unto himself. While possessing freedom, he did not have the false sense that he existed free of anything else, that he was non-determined. He was not conscious of being a separate, isolated self, but cleaved unto God in a communion of love and united all creation in love unto himself. Since he did not have diversified thoughts but only simple, pure awareness, he did not identify himself with such thoughts, as we do today. And since he was not distracted by and enslaved to his senses, he did not identify himself with his physical body, as we do. Thus, for all these reasons, we can say that, while being a person endowed with self-awareness, he was truly selfless.

When he was still in this state of pristine simplicity, man always acted in accordance with nature: both in accordance with his own human nature (or human essence), and with the common nature of all creation. This is the same as saying that he acted only in accordance with the ordering, directing Principle of all nature: the Tao/Logos. His will, created pure by God, followed the Tao in all things – not out of necessity, as did other creatures, but freely, out of love. His freedom of will made him unique among all creatures, though not separate from them. This quality of freedom not only made for the possibility of his unique human personhood; it was also part of what made him «in the image of God».

As God is free, so likewise man is free. But between God and man there remained a fundamental difference. God is entirely sufficient unto Himself: self-existing, non-determined, unconditioned, standing in need of nothing. He is absolute Possibility. Man, on the other hand, is conditioned by the very fact that he was brought into being not by himself. His very minute-by-minute existence – not only his creation – is dependent on God. The character of his existence is determined by his own God-given human nature, and by the common nature of the created order of which he is a part. He has the ability to freely choose his actions within this determined, conditioned existence. If he chooses to act according to nature, and thus according to the Tao Who orders nature, all will go well. But if he does not act naturally, he gets out of harmony with both the Tao and with nature, and thus sets himself at odds with that which determines his very existence.

As long as man, in his self-awareness, remains humbly aware that he does not exist of himself, that of himself he is nothing at all, he will do what is natural to him. He will do it freely and at the same time automatically – that is, spontaneously, because his «free will» will naturally fall in line with nature without his having to stop and consider anything.

When man begins to harbor the illusion of self-sufficiency, however, he becomes a «self» in the modern sense of the word: an individual desiring things for himself and pitting himself against other individuals.

If such was the possible consequence of human freedom, why did God allow for it? It was in order to allow for love. Love must be freely given; it cannot exist without freedom. If God had not endowed the human essence with this quality, the world would be a cold, impersonal, entirely programmed environment.

2. The Primordial Departure

When man, in wrongly using his free will, first departed from the Way (Tao), he corrupted his primal simplicity and became fragmented. Divested of the primal glory, of the garment of Uncreated Light that had enveloped him, he now found himself «naked» (Genesis 3:7). His spiritual corruption and death made him subject to physical corruption and death.412

«After his transgression», writes St. Macarius of Egypt († A.D. 390), «man’s thoughts became base and material, and the simplicity and goodness of his mind were intertwined with evil worldly concerns».413His will became divided. Now his «natural will», which remained inclined to follow the Way in all things, was set against his «free will», which had now taken on itself an inclination to depart from the Way.

Before his primordial departure from the Way, man had experienced only that which was natural to him. Now, however, he also experienced what was unnatural to him. Thus he self-willfully usurped the «knowledge of good and evil», destroying the primal simplicity and bringing duality into the world.

Before, man had been spontaneous, like a child. At every step, he freely chose, without thinking, to act according to nature, according to the Way. Now, however, at every step he had to stop and think, to calculate: «Should I follow the Way or not?» Thus he became a complex being, inwardly divided, and always vacillating.

Only God is self-existent. When man began to fall under the illusion of being a self-existent individual, he was essentially making himself into a little god. This was the meaning of the primordial trap into which he fell: «Knowing good and evil, you will be as gods».414

Man had been created to rise, in his simple and uncompounded nature, in noetic contemplation of the simple and uncompounded God. To rise in love, and to unite all of creation with himself in love, raising it also to the Creator. Instead of regarding the Way, however, he chose to regard what was easier and closer at hand: his own visible self. Instead of rising with God, he fell in love with himself.

Man had been meant to find pleasure in his limitless ascent to God and in loving communion with Him, the Source of all things. But, in falling in love with himself, he began rather to seek pleasure from what was closer to him: his body and his senses. All evil in the world can be traced to these two things: self-love and love of sensual pleasure.415

Man had been created to desire God, the Uncreated Source of his joy. But, in falling in love with himself, he had instead begun to desire created things.

Because of all this, God allowed suffering to enter the world. He did this not out of vengeance, but out of love for man, so that through suffering arising from self-love, sensual pleasure, and the resulting desire for created things, man might see through the illusion of his self-sufficiency and return to his original designation: the state of pristine simplicity and communion with the Way.

Knowledge of God in the Earliest Historical Cultures

After his primordial departure from the Way, man as a whole was still more simple and innocent, closer to God and nature, than he is today. Thus, his knowledge of God was more pure. This is substantiated by records that have come down to us of the earliest periods of ancient civilizations. The religion of Egypt’s first dynasty, for example, was much more pure than the forms of polytheism that arose in later dynasties. Mircea Eliade writes: «It is surprising that the earliest Egyptian cosmogony yet known is also the most philosophical. For [the Supreme God] Ptah creates by his mind (his ‘heart’) and his word (his ‘tongue’).... In short, the theogony and cosmogony are effected by the creative power of the thought and word of a single God. We here certainly have the highest expression of Egyptian metaphysical speculation.... It is at the beginning of Egyptian history that we find a doctrine that can be compared with the Christian theology of the Logos».416

The same is true for the primal period of Chinese civilization. The oldest book of Chinese history, the Shu Ching (Book of Documents), relates that in China’s first dynasty, the Hsia (ca. 2300–1700 B.C.), the people believed in one supreme God, Whom they called Shang Ti – Shang meaning «above», «superior to», and Ti meaning «ruler» or «lord». «At this point», writes historian John Ross, «the very threshold of what the Chinese critics accept as the beginning of their authentic history, the name of God and other religious matters present themselves with the completeness of a Minerva. We are driven to infer that the name and the religious observances associated with it are coeval with the existence of the people of China.

«It is therefore evident that the belief in the existence of one Supreme Ruler is among the earliest beliefs of the Chinese known to us. Of an earlier date, when no such belief existed or when the belief in polytheism did exist, we find no trace. Nowhere is there a hint to confirm the materialistic theory that the idea of God is a later evolutionary product of a precedent belief in ghosts or departed ancestors, or that the belief had arisen indirectly from any other similar source».417

During the next dynasty, the Shang (ca. 1700–1100 B.C.), the supreme Deity was more commonly called by the name T’ien – meaning «Heaven» – though the name Shang Ti continued to be used interchangeably with it, sometimes side by side.418The Chinese Emperor had to possess what was called the «mandate of Heaven» or the «mandate of Shang Ti», which he earned by living and ruling virtuously. If ever he ceased to rule according to the Way of Heaven, he would lose the mandate and fall from power.419 This understanding of government remained intact in China until the early twentieth century.

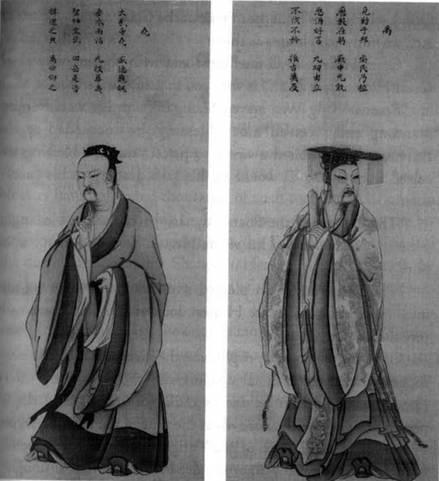

Ma Lin (ca. A.D. 1180–1256), Portraits of Emperor Yao (left) and of Emperor Yü of the Hsia Dynasty. Emperor Yao ruled China along with his joint-ruler Shun in the twenty-third century B.C. The Shu Ching records of Emperor Shun: «He sacrificed to Shang Ti». Shun appointed Yü as his successor in 2205 B.C. It was ancient sage-kings such as these, from the dawn of China’s recorded history, whom Lao Tzu called «subtle, mysterious, fathomless, and penetrating» in chapter 15 of the Tao Teh Ching.

In China’s oldest book of literature, the Shih Ching (Book of Odes), which dates from the middle of the Chou dynasty, 800–600 B.C., we find such phrases as these:

«Great Heaven is all-intelligent and with you in every place, Great Heaven sees all and is with you in your wanderings».

«Because King Wen served Shang Ti with his whole understanding and received much blessing, he succeeded to the throne.... He exhibited a virtue so perfect that the blessings received from Shang Ti would for his sake descend to his successors».

«The founder of the Shang [dynasty] received the blessing of Heaven, and because of his virtue Heaven bestowed mercy upon him».

«The arrogant men are pleased, while the toiling men are anxious. Azure Heaven, azure Heaven, look at those arrogant men, pity these toiling men!»420

Of all the primordial peoples save the Hebrews, the Chinese – together with their racial cousins the native North Americans – retained the purest understanding of the one God, the supreme Being. Nevertheless, even at the time of the first and second dynasties in China, much of man’s original knowledge of God had been lost due to the primordial departure. Heaven, although it guided and directed the affairs of men, was often seen as being painfully distant; in the Shih Ching it is often referred to as «remote Heaven». Only the Emperors had the right to offer sacrifices to Shang Ti/Heaven, and even they were frequently to lament that «Heaven is difficult to rely on». The Duke of Chou (eleventh century B.C.) went so far as to say, «Heaven cannot be trusted».421

In ancient China as in other primal cultures, we see a gradual movement from simplicity to complexity, as the effects of the primordial fall from the pristine simplicity became more fully entrenched in man’s nature. Man was no longer merely asking, Should I follow the Way of Heaven or not? Now he was asking, What is the Way?

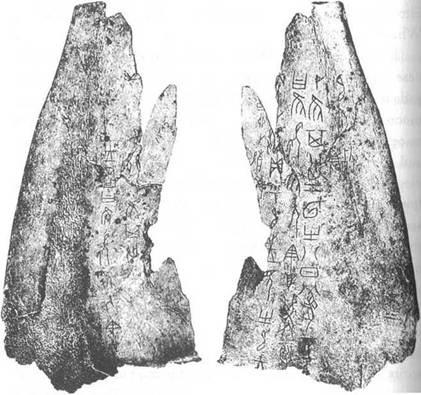

In becoming more distant from the Creator, the ancient Chinese sought out inferior deities: the spirits of their ancestors, the gods of hunting and agriculture, the spirits of the sky, earth, sun, moon, wind, etc. To seek out the will of Heaven, they frequently resorted to divination: heating up a tortoise shell until it cracked, and then interpreting the message encoded in the cracks. Archeologists have uncovered thousands of such tortoise shells used in imperial divination, dating from the Shang dynasty. From the inscriptions on them, it appears that the Emperors never invoked the distant and awesome Shang Ti/Heaven directly through the oracles, but only invoked the spirits of their ancestors as intermediaries.422

As centuries passed, the original monotheism of China continued to be obscured. Since the Chinese culture is so strongly based in tradition, however, the ancient religion could never disappear entirely. Above all, it was preserved in the state worship. The Emperor continued to offer the Great Sacrifice to Shang Ti twice a year, at the winter and summer solstices, according to ancient custom. This practice extended into modern times, and ended only with the fall of the Manchus in 1911.423

Even from the popular mind, the ancient monotheism could not be completely eradicated. To Westerners it is a little-known fact that, in China and Taiwan even today, vestiges of the original Chinese religion are found in the Taoist and Buddhist temples. When people come to these temples, they burn incense and pray to Shung Ti at a special place in the narthex, and only then do they enter the main temple area.

Inscriptions on oracle bones from the Shang dynasty, ca. 1700–1500 B.C.

Still, it must be conceded that much of Chinese religion has descended to polytheism through the centuries, and that the worship of the one God, Shang Ti, has been confused by pantheons of deities of various ranks.424

The same would have happened in ancient Hebrew culture as happened in China – and at many times in Jewish history it almost did happen – but God, through the Prophets, continually called this people back to the worship of Him alone. He intervened in this way because it was out of the Hebrew race that He was to one day take flesh and reveal the ultimate mystery of His Being to the world.

One of the oldest known images of Confucius: a stone engraving modelled after a painting by Wu Tao Tzu, eighth century A.D. The man on the right is believed to be Tseng Tzu, one of Confucius' disciples. In ancient times a student walked a few paces behind his teacher, to show his respect.

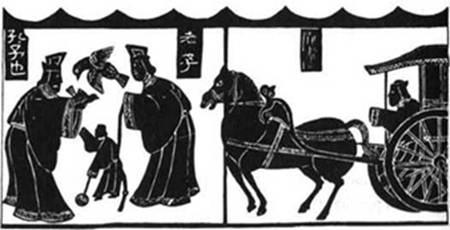

Confucius visiting with Lao Tzu. Legends of their meeting were recorded by Chuang Tzu (third century B.C.) and Ssu-ma Ch’ien (second century B.C.). See Arthur Waley, Three Ways of Thought in Ancient China, pp. 12–18, and James Legge, The Sacred Books of the East, vol. 39, pp. 33–35.

Chapter Two: Seeking the Way of Return

4. Lao Tzu and Confucius

When Lao Tzu and Confucius were born into the world in the sixth century B.C., the religion of China – although still essentially monotheistic and more elevated than the religions of other cultures such as the Greek and Roman – was considerably distanced from the pristine simplicity. Both Lao Tzu and Confucius harked back to a time when people were closer to Heaven and to nature. For, like most ancient cultures, the Chinese had preserved a memory of a time in dim antiquity, a «golden age», when man had been in a pure state. Lao Tzu wrote:

Immeasurable indeed were the ancients...

Subtle, mysterious, fathomless, and penetrating.425

Painting of Confucius by Prince Ho Shuo Kuo, A.D. 1735. On the top are Chinese characters of an ancient script which read: «Confucius, the Sage and the Teacher».

Confucius studying the music of the ancients in order to gain insight into their lives. A drawing by Ku K’ai Tshi.

In order to return to the time when man was closer to Heaven, Confucius pored over the ancient Classics, attempting to unlock the knowledge of the ancients and to faithfully transmit their tradition to subsequent generations. He hoped that, by effecting a return to the ways and rites of previous times, he could bring about a radical reform in the corrupt government of the late Chou dynasty. At the end of his life, he felt that he had failed in his purpose.426 There was something that the ancients possessed that he could not retrieve by mere study. He saw that the Great Sacrifice to Heaven had been corrupted, and that its meaning had been lost. «At the Great Sacrifice», he said, «as for all that comes after the libation, I had far rather not witness it!» When someone asked him the meaning of the Great Sacrifice, he said, «I do not know. Anyone who knew its meaning could deal with all things under Heaven as easily as I lay this here» – and he laid his finger upon the palm of his hand.427

Lao Tzu, although he was also well versed in the Classics (tradition says that he was the keeper of the Royal Archives), chose path very different from that of Confucius. In order to return to the state when man was nearer Heaven, he took the path of direct intuition.

Lao Tzu sought to return not merely to the primal period of Chinese history, for that was comparatively late in the history of mankind, dating from the time of the great Flood in the twenty-fourth century B.C. (The most ancient Chinese historical documents tell of a great flood occurring in the twenty-fourth century B.C., which was the same time it occurred according to Biblical chronology).428 Ultimately, he was harking back to the state in which man was first created, before he first departed from the Way:

The primitive origin (of man):

Here indeed is the clue to the Way.429 430

(The parenthetical phrase “of man” was added by Gi-ming Shien by way of exegesis. In the translation notes of Fr. Seraphim, “clue” (jhî ) is also rendered as “main-thread.”)

Lao Tzu knew that in his primitive origin, man was in a state of undifferentiated consciousness, of direct apprehension of Reality. He called this the «pristine simplicity», the «uncarved block», the «return to the babe».

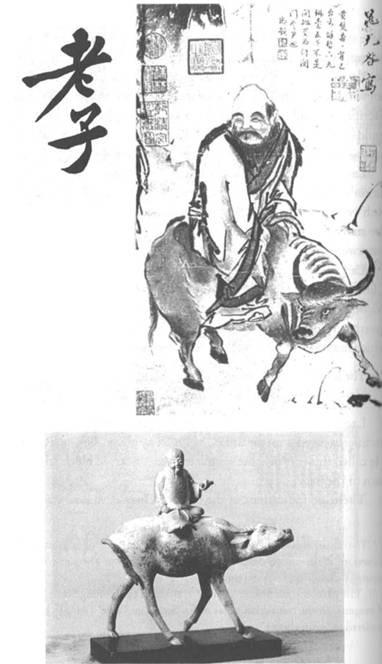

A painting and a sculpture from the Sung dynasty (A.D. 960–1279) of Lao Tzu leaving the world on a water buffalo. The calligraphy: «Lao Tzu».

There are indications in the Tao Teh Ching as to how Lao Tzu endeavored, to return to this state. In one place, for example, he says to «block the passages, shut the doors [of the senses]» and to «attain inmost emptiness, observe true quiet»,431meaning to close one’s eyes and allow one’s spiritual awareness or «higher mind» to rise above the multiple deliberations, images and concepts in one’s head. In this way, Lao Tzu could step back from his thoughts and look at them objectively, thereby realizing that his thoughts were not him.

Most people identify themselves with their thoughts. When thoughts appear, they assume that these thoughts are them, that the sum total of their thoughts, memories and corresponding feelings make up the sum total of their personalities. But thoughts, as Lao Tzu realized, are only fragments which flit through the mind. Of themselves they have no reality.

Getting wrapped up in their thoughts, people become the victims of compulsive thinking: habitual thought-patterns which attach themselves to certain feelings. Finding their very identity in these patterns, they forget who they really are, that they are immortal spirits. Having lost sight of the one, immortal human nature which is common to all, they become trapped in their individuality and in the desires of their false identity.

Lao Tzu, in rising above compulsive thinking and desire for created things, was able to glimpse the common nature of all humanity. No longer did he feel the need to assert his individuality, or to strive against others for rights and privileges. Thus, while retaining an awareness of himself as an immortal spirit, he became selfless. This can be seen from several passages in the Tao Teh Ching:

The Sage has no fixed will.

He regards the people’s will as his own.432

He who takes upon himself the humiliation – the dirt – of the people

Is fit to be the master of the people.433

The man of the highest virtue

Is like water which dwells in lowly places.

In his dwelling he is like the earth, below everyone.

In giving, he is human-hearted.

His heart is immeasurable.434

I have Three Treasures, which I prize and hold fast.

The first is gentle compassion;

The second is economy;

The third is not presuming to take precedence in the world.

With gentle compassion I can be brave.

With economy I can be generous.

Not presuming to take precedence in the world,

I can make myself a vessel fit for the most distinguished services.435

In finding the one nature common to all people, Lao Tzu was able to regard all people equally:

Treat well those who are good,

Also treat well those who are not good;

Thus is goodness attained.

Be sincere to those who are sincere,

Also be sincere to those who are not sincere;

Thus is sincerity attained.436

But there is in the Tao Teh Ching something even higher and nobler than this. Lao Tzu attained to the realization of returning good for evil:

Act without acting,

Work without working,

Taste without tasting,

Exalt the low,

Multiply the few.

Requite injury with kindness.437

As the great Chinese scholar James Legge points out: «The sentiment about returning good for evil was new in China, and originated with Lao Tzu.... Someone of Confucius’ school heard the maxim, and, being puzzled by it, consulted Confucius. The sage, I am sorry to say, was not able to take it in. He replied, ‘What then will you return for good? Recompense injury with justice, and return good for good’».438

To Confucius can be given the credit of being the first in China to enunciate the «golden rule». «What you do not want done to yourself», he said, «do not do to others».439This represents the perfection of natural human virtue, which Confucius admirably embodied. But the higher, Divine law of loving even one’s enemies and persecutors could be arrived at only by finding the original image of man’s nature, as Lao Tzu did. Hence it was Lao Tzu and not Confucius who discovered it.

If one were to distill Lao Tzu’s teaching on human conduct, it would be simply that one should do what is natural. To be natural, however, one must first find the original nature of man. Acting in accordance with this nature, one acts in accordance with the Tao. Thus one no longer has to be choosing all the time, but can be wholly spontaneous. Being spontaneous, one can forget oneself and give oneself over for the good of others. One will do what is right, not only without having to think about it, but without even knowing it! Such is the state of primal simplicity, before man usurped the «knowledge of good and evil». Lao Tzu said:

Superior virtue is unconscious of its virtue,

Hence it is virtuous.

Inferior virtue is conscious of its virtue,

Hence it is not virtuous.440

5. The Tao

From the testimony of the Tao Teh Ching, it is clear that Lao Tzu was, to some measure, able to return to the state of the uncarved block in which man had lived before his departure from the Tao. Through the cultivation of objective awareness, he attained to intuitive perception analogous to that of primordial man. «Use your light» (kuang )), he said, «to return to the light of insight (ming

)».441 That is, using the natural light of the human spirit, return to the undifferentiated consciousness, direct apprehension of Reality. Elsewhere he speaks of «following the light of insight».442

«He who completely knows his own nature», said Mencius, «knows Heaven».443Such was the case with Lao Tzu. By realizing the human nature common to all, he rose to intuitive knowledge of the Divine. Having intuited the presence of the original ordering Principle behind all creation, he also realized the inner principles of created things: the «ideas» of things which must exist prior to the things themselves.444 «He who apprehends the mother», he wrote, «thereby knows the sons».445

Gi-ming Shien explains further:

«Order is natural and necessarily requires a directing principle, for it is unimaginable that order is produced by the ordered individuals themselves. If there were no directing principle, how could there be proportion, symmetry, and the adaptation of one thing to another? There must, therefore, be an organizing power which orders – as, for example, in the seasons. The principle of seasons, from which the seasons proceed in an orderly and never-failing fashion, must exist before the seasons themselves. The ultimate principle is, therefore, of prime importance, and it is this that Lao Tzu calls the Tao....

«According to Chinese Taoist philosophy, the Tao or the One is prior to all things, and from the Tao or One all things derive their order. We may say, therefore, that the Tao or the One... produces all things».446

The realization of this Creator-Principle was, of course, not new with Lao Tzu. Chinese sages before him, as well as the philosophers of Greece and other cultures, had spoken of the same first Cause. No one, however, had actually described it in human terms as well as did Lao Tzu in the Tao Teh Ching. The greatest achievement of this man who so valued non-achievement, was that he came closer than any person in human history to defining the Indefinable Tao without the aid of special revelation.

6. Mysterious Teh

Lao Tzu did not know, nor could he have attained purely through intuition, the state of intimate personal union with the Tao that the first man had enjoyed, when he had been wholly infused with Uncreated Energy and clothed in it as in a garment of Light. However, Lao Tzu did partake of and experience this Energy/Light acting on him and in the world. He called it the «Mysterious Power» (The ) of the Tao:447

All things arise from Tao.

They are nourished by Teh.

Thus the ten thousand things all respect Tao and honor Teh.

Respect of Tao and honor of Teh are not demanded,

But they are in the nature of things.

THE SEAL: «Mysterious Teh» (Tao Teh Ching, chs. 10, 51, 65).

Deep and far-reaching is Mysterious Teh!

It leads all things to return,

Till they come back to the Great Harmony!448

Teh, says Gi-ming Shien, is the «realizing principle» and «principle of manifestation» of the Tao. The Primal Essence of the Tao cannot be fathomed, but the Tao can be experienced through the manifestation of its Power or Teh.449 Gi-ming's teaching concerning Teh is in keeping with that of other Chinese commentators on the Tao Teh Ching. Classical scholar Yen Ling-feng writes: «Teh is the manifestation of the Way. The Tao is what Teh contains. Without the Tao, Teh would have no power. Without Teh, the Tao would have no appearance». The thirteenth-century writer Wu Cheng, commenting on chapter 51 of Lao Tzu’s book, asserts that Teh is Divine and Uncreated as is the Tao itself: «The Tao and Teh is mentioned at the beginning of this chapter, but only the Tao is mentioned later. This is because Teh is also the Tao».450

The word Teh – in those places where Lao Tzu employs it to speak of the

Uncreated Power of the Tao – corresponds to the English word «Grace». As the great Russian saint, Seraphim of Sarov, affirms, pre-Christian God-seekers such as Lao Tzu knew what it meant to cultivate this Grace in themselves. They had, he says, «a clear and rational comprehension of how our Lord God the Holy Spirit acts in man, and by means of what inner and outer feelings one can be sure that this is really the action of our Lord God the Holy Spirit and not a delusion of the enemy».451This understanding is found in several places in the Tao Teh Ching. Here we have translated Teh as «Grace».

Cultivate Grace in your own person,

And it becomes a genuine part of you.

He who follows the Way

Is at one with the Way.

He who cultivates Grace

Is at one with Grace.

When you become the valley of the world.

Eternal Grace will never depart.

Such is the return to the babe.452

7. The Oneness of the Tao

The first quality of the Tao that Lao Tzu discerned was its oneness. He wrote:

Once there was a time when all things became harmonized through the One:

The heavens receiving the One became clear;

The earth receiving the One became calm;

Spirits receiving the One became divine;

All things receiving the One began to live.453

The realization of the Tao’s oneness arises from the fact that it is and must be without peer, beyond any limitation. Gi-ming Shien explains:

«Let us now look into the real existence of eternal and infinite Being, which transcends space and time and is unlimited in its nature. What can the nature of such existence be? Regarded from the standpoint of its lack of limitation, it is completely independent, that is, absolute. ‘Absolute’ means that it is relative to nothing and is self-sufficient».454

Lao Tzu was not the first to arrive at the realization of the Absolute One. We find the same understanding, for example, in the pre-Socratic Greek philosopher Parmenides. What was new with Lao Tzu – or at least more developed than in any philosopher before him – was the metaphysical insight that the Tao, the Creator and Sustainer of the universe, was utterly selfless.

8. «Nothingness»

Many times in the Tao Teh Ching, Lao Tzu speaks of «nothingness» or «emptiness» (wu ) in connection with the Tao. Modern Western interpreters, and some Chinese as well, have made the mistake of thereby assuming that the Tao is nothingness or non-being. This misconception has been furthered by mystics and metaphysicians who, through meditation (or even, in the modern West, through hallucinogenic drugs), have had a glimpse of the non-being out of which they were called into existence by their Creator. Because this non-being is eternal, people have concluded that it itself is the Tao, the Absolute, or God. As Gi-ming Shien makes clear, however, non-being is not to be equated with the Tao:

«The interpretation of ‘nothingness’ in the philosophy of Lao Tzu by modern Chinese scholars is often one of two extremes. Some have taken it as nihilism, and some have interpreted it in terms of being.... Fung Yu-lan is an example of the latter. In his hook The History of Chinese Philosophy, he regards the particulars or individuals as being, and the universal, the metaphysical One, or Tao, as non-being.... This interpretation, however, is far from the real meaning of nothingness in Lao Tzu. For, although Tao is infinite and indefinable... it remains in the realm of existence with particular things. We may say that Tao or the metaphysical One is the infinite or the all-embracing principle. However, despite the fact that we cannot give it a definite particular name, the all-embracing principle does exist, and, therefore, is not the meaning of nothingness».455

Gi-ming observes that, while nothingness is not the Tao, it is in the nature or essence of the Tao:

«The nature of Being is said to be nothingness because Being is absolutely complete, in need of nothing, conscious of no wants. This is why the principle of nothingness in the philosophy of Lao Tzu is ‘nameless’».456

«The real meaning of ‘nothingness’ or non-being is based on spontaneity.... Spontaneity is the nature of being; the full development of spontaneity results in forgetfulness; forgetfulness results in a feeling of nothingness».457

In other words, because the Tao is self-existent, self-sufficient, and conscious of no wants, it can create, give and sustain life and at the same time seek nothing of its own. As Gi-Ming Shien says, the Lao «forgets itself and its own existence»458, being totally spontaneous and selfless. In chapter 34 of the Tao Teh Ching, we read:

The great Tao follows everywhere....

All things depend on it for life; none is refused.

When its work is accomplished, it does not take possession.

It clothes and feeds all things, yet does not claim them as its own.

Ever without desire, it may be named small.

Yet when all things return to it,

Even though it claims no leadership

It may be named the great.459

Did Lao Tzu first become aware of the selflessness of the Tao, and then undertake to model his own life after the Way of Heaven? Or did he first reach a certain level of selflessness which enabled him to see Reality objectively, and from this clarity of insight begin to speak of the selflessness of the Tao? This we cannot say, but from the Tao Teh Ching one thing is certain: Lao Tzu saw the selflessness, self-forgetfulness and spontaneity of primordial man as an image and a reflection of the Creator-Tao itself. In this sense as in others, man had been made in the image of God.

9. The Benevolence of the Tao

Lao Tzu, then, had arrived at two great affirmations concerning Absolute Being: its oneness and its selflessness. From these realizations alone, however, he could not fully realize the other primary ontological fact of the Tao: the fact that the Tao is a Person.

It is true that Lao Tzu approached this realization, for as he observed the Tao at work in nature, he saw actions that were benevolent, like those of a person:

All things arise from the Tao.

By the Power of the Tao (Teh) they are nourished,

Developed, cared for,

Sheltered, comforted,

Grown, and protected.460

Elsewhere Lao Tzu wrote of the Tao’s benevolence:

The Tao of Heaven is to benefit, not to harm.461

He also said that the Tao, while not being a «respecter of persons» (i.e., paying no attention to distinctions of class, race, creed, wealth, etc.), aligns itself to those who are good:

The Tao of Heaven makes no distinctions of persons.

It always helps the virtuous.462

Here, as in several other places, Lao Tzu speaks of the «Tao of Haven» in the same way his contemporaries like Confucius spoke of «Heaven», the supreme Deity of the ancient Chinese (T’ien (Heaven), as a reference to the Supreme Being, is to be distinguished from t’ien-ti (heaven and earth), which refers to the totality of the created order, and is often translated as «nature». For Lao Tzu, while the Tao was benevolent, nature was not, in and of itself. Thus in the Tao Teh Ching we read: «Heaven and earth are not benevolent» (ch. 5)).463In fact, the above quotation from the Tao Teh Ching is found in another Chinese work, the Tso Chuan, which is based on texts written centuries before Lao Tzu. The original version says «Great Heaven», for which Lao Tzu substituted the «Tao of Heaven».464

The phrase «Tao of Heaven» appears in several other places in the Tao Teh Ching, as in:

Without peeping through your window

You can see the Tao of Heaven.

The Tao of Heaven does not strive, and yet it overcomes.

It does not speak, and yet is answered.

It does not ask, yet things come to it of themselves.465

Elsewhere in the Tao Teh Ching, Lao Tzu employs the word «Heaven» by itself, and it is clear from the context that he considers it synonymous with the Tao.466 The Shih Ching, whose passages on Heaven we have quoted above, says, «Heaven has let down its net to enclose all».467Lao Tzu made use of this same image and expanded upon it:

Vast is Heaven’s net;

Sparse-meshed it is, and yet

Nothing can slip through it.468

Further, the Tao Teh Ching speaks of serving, following, and being united with Heaven:

In governing a people and serving Heaven,

There is nothing like using restraint.

Mercy alone can help you win a war.

Mercy alone can help you defend your state.

For Heaven will come to the rescue of the merciful,

And protect him with its Mercy.

This is known as the virtue of not striving....

This since ancient times has been known as the ultimate unity with Heaven.

In another place, Lao Tzu says:

Some things are not favored by Heaven.469

For Lao Tzu, then, the Tao – which he also called the Tao of Heaven or simply Heaven – was not entirely impersonal, as some recent scholars have claimed. Lao Tzu could even be said to have had a «relationship» with the Tao, just as Confucius had a relationship with Heaven. This «relationship» was expressed in constant observation of the workings of the Tao of Heaven, and in constant care to live virtuously, in accordance with it, catching and realigning oneself if ever a deviation occurred.

10. The Mystery of «I AM»

Nevertheless, although Lao Tzu knew the Tao to be a benevolent Being, the full meaning of the Tao as a Personal Absolute – as a Being with Whom one could hold person-to-Person communion – remained outside the scope of his metaphysical insight. Again, such a unique revelation could not be attained even by the intuition of people of the most virtuous lives and purified minds; rather, it had to be given, and God was providentially preparing humanity to receive it. He had been unfolding the secret life of His Divine Being gradually, at certain key moments in history, for humanity could not receive it all at once.

God first revealed the fullness of His Personhood to an oftoppressed nomadic people, the ancient Hebrews. He chose them for this because it was out of their race that He was to become incarnate many centuries later.

The contemporary Russian mystical writer, Archimandrite Sophrony († 1993), writes:

«The problem of the knowledge of God sends the mind searching back through the centuries for instances of God appearing to man through one or other of the prophets. There can be no doubt that, for us, one of the most important happenings recorded in the chronicles of time was God’s manifestation on Mount Sinai where Moses received new knowledge of Divine Being: ‘I AM THAT I AM’ – Jehovah.470 From that moment vast horizons opened out before mankind, and history took a new turn.

«Moses, possessed of the supreme culture of Egypt, did not question that the revelation that he was so miraculously given came from Him Who had indeed created the whole universe. In the Name of this God, I AM, he persuaded the Jewish people to follow him. Invested with extraordinary power from Above, he performed many wonders. To Moses belongs the undying glory of having brought mankind nearer to Eternal Truth. Convinced of the authenticity of his vision, he issued his injunctions as prescripts from on High. All things were effected in the Name and by the Name of the I AM Who had revealed Himself. Mighty is this Name in its strength and holiness – it is action proceeding from God. This Name was the first ingress into the living eternity; the dayspring of knowledge of the unoriginate Absolute as I AM».471

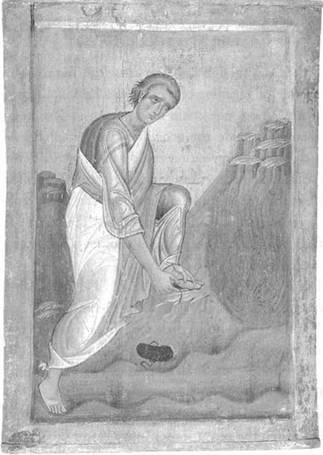

Icon of the Prophet Moses before the burning bush on Mount Sinai, where God tells Moses, «Put off your shoes from your feet, for the place on which you are standing is holy ground». In the book of Exodus we read that «the bush burned with fire, yet it was not consumed» (Exodus 3:2, 5). This fire was the Energy (Teh) of God, which Moses was given to behold with spiritual eyes as Uncreated Light. From out of this Light God spoke to Moses, revealing to Him the mystery of His Personhood in the holy name I AM. This early thirteenth-century icon is from the ancient Eastern Orthodox monastery of St. Catherine, located near to where Moses received the revelation on Mount Sinai.

Having received this new revelation of the Personal Absolute, Moses received into his mortal body – albeit temporarily – the «clothing of Light» that primordial man possessed. For it is recorded that «the skin of Moses’ face shone», such that he had to put a veil over his face when speaking to the children of Israel.472 This revelation of the Uncreated Energy (Teh) of God, writes St. Macarius of Egypt, was a «prefiguring of the true glory» which would later descend upon followers of the incarnate God.473

11. The Paradox of Personhood and Selflessness

Now it may be asked why Lao Tzu, without the special revelation accorded to Moses, could not have fully realized the primary fact of the Absolute as Person. The answer to this question might be discovered in the unique combination of facts with which Lao Tzu was already working: the oneness of the Absolute and its selflessness («nothingness»). This combination prevented him from seeing even the possibility of the Creator being a Person such as Moses knew Him to be. For if the Tao or the One were simply a Monad, dwelling in eternal metaphysical solitude, it could not be wholly selfless and intimately personal at the same time.

In order to explain this, let us draw an analogy from the human person. A human being’s personhood is that indefinable essence which makes him uniquely that person and not someone else.474 But behind his personhood, as it were, is the one human essence common to all persons.475 By going beyond attachment to his senses, his thoughts, and his visible self, Lao Tzu was able to find this shared human essence or nature; and in finding it, he was able to be a self-aware person and still be selfless, caring for all persons without distinction.476

As far as Lao Tzu knew, however, the Tao was alone, without peer, sharing its Primal Essence or Nature with no one and nothing, either created or uncreated. Being such, it could not be selfless and a Person at the same time. If the Absolute were metaphysically alone and also a Person, it would have to be a great cosmic Egotist and Despot – which was certainly not what Lao Tzu perceived of the Tao.

In other words, Lao Tzu could say «I am» and still be selfless because he shared his created nature with other co-equal persons. From his point of reference, however, he could not see how the Tao could say «I AM» and also be selfless, unless the Tao shared its Uncreated Essence with other Persons equal to itself. But for the Tao to share its Essence was impossible in Lao Tzús view, given the primary truth that the Absolute is one and without peer.

The Consequences of an Incomplete Understanding of God

In the time of Lao Tzu, the primary facts which mankind as a whole knew about God made for an incomplete understanding of Him. If we take the oneness and the selflessness of God together, we end up with an impersonal Absolute. This is precisely what happened in China. By the time of the Warring States (475–221 B.C.), even those personal qualities which Lao Tzu had ascribed to the Absolute were no longer being acknowledged by the philosophers. As Taoist historian Eva Wong observes: «The Taoism of the Warring States came up with a different conception of the Tao. In the Tao Teh Ching, the Tao... had a benevolent nature. This quality disappeared in the Chuang Tzu and the Lieh Tzu. The Taoist philosophers of the Warring States saw the Tao as a neutral force. It was still the underlying reality of all things, but it was no longer a benevolent force. Moreover, the Tao had no control over the course of events: what would happen would happen, and nothing could be done to facilitate it or prevent it».477

This total depersonalization of the Tao had direct consequences on the spiritual life of the people. When Taoism came into being as a religion some seven centuries after Lao Tzu, it relied first of all on the cultivation of natural (created) energy by impersonal, mechanical means in order to bring about salvation, inner transformation, and physical immortality. As a result, by the eighteenth century A.D. the Taoist master Liu I-ming was to lament: «There are seventy-two schools of material alchemy, and three thousand six hundred aberrant practices. Since the blind lead the blind, they lose sight of the right road; they block students and lead them into a pen.... The reason the spiritual treasure does not appear to seekers is that they themselves will not allow it to do so – what a pity that false people spend their lives madly in sidetracks».478Here Liu I-Ming was reflecting the teaching of Lao Tzu himself, who wrote:

If I have even just a little sense,

I will walk on the main road and my only fear will be straying from it. Keeping to the main road is easy,

But people love sidetracks.479

Such are the possible deviations arising from an understanding of God or the One as being wholly impersonal. On the other hand, if we take the oneness

and the personhood of God together, we end up with a God dwelling in metaphysical solitude, making way for a distorted view of Him as a stern, demanding Judge, a petulant Egotist, and a severe Lord of vengeance. This view manifested itself at some early stages of Chinese history, many centuries before Lao Tzu, such as when the Duke of Chou told the soldiers of the Yin dynasty which he had conquered, «The merciless and severe Heaven has greatly sent down destruction on the Yin. You, many officers of Yin: now our Chou King has grandly and excellently taken over God’s affairs. There was the heavenly charge: destroy Yin».480This view of God prevailed to a much greater extent, however, in the development of Judaism – and later of Islam – as we shall see.

13. The Mystery of the Triad

To the Hebrews was given the revelation of the One Personal Absolute; to Lao Tzu was given the realization of the One Selfless Absolute. Both of these were true, yet each one seemed to cancel out the other. To effect a reconciliation, and to overcome the distortions arising from each opposing view, a missing piece had to be uncovered in the Nature of the Absolute. God would have to reveal the ultimate mystery of His Being: the mystery of the Triadic One.

When this mystery was revealed, the oneness of God was shown to contain three Persons: not three Gods (as in polytheism), but three Persons in one God. Here it could be seen that the Tao in fact did share its unknowable, formless Essence with other Persons equal to itself. These Persons share a common Divine Essence, just as human beings share a common human nature or essence.

We have spoken of the selflessness which humans lost after they departed from the Way, and of how Lao Tzu undertook to return to this state of self-forgetting by finding the single human essence, the original nature of primordial man. Now, with the revelation of the Triadic One, it could be seen how man’s original and potential selflessness is precisely an image of the selflessness which exists in the three Persons of the Absolute Who share a single Divine Essence.

Since man’s departure from the Way, the one human nature has become divided, and human persons have become isolated from each other; not so with the three Divine Persons, for They dwell in one another. The works of human persons are distinct; not so those of the Divine Persons, for the Three have a single will, a single power, a single operation. They cleave to each other, having their being in one another.

This perfect, indwelling love between the Persons of the Godhead is ultimately what is meant by the words, «God is love» (I John 4:8). God’s love is not merely extended to the universe created by Him, for God was Love even before the foundation of the world. As Fr. Dumitru Staniloae of Romania († 1993) writes:

«Love must exist in God prior to all those acts of His which are directed outside Himself. Love must be bound up with His eternal existence. Love is the ‘being of God’».481

Each Person of the one God, having His being in the Others, is therefore wholly selfless, possessing the quality of spontaneity, self-emptying or self-forgetting («nothingness») that Lao Tzu intuited in the Tao. Each Person (each «I») forgets Himself before the Others, emptying Himself in perfect love; and in this ineffable love lies the secret of God’s oneness. Fr. Dumitru explains:

«Each Divine ‘I’ puts a ‘Thou’ in place of Himself.... The Father sees Himself only as the subject of the Son’s love, forgetting Himself in every other aspect. He sees Himself only in relation with the Son. But the ‘I’ of the Father is not lost because of this, for it is affirmed by the Son Who in His turn knows Himself only as He Who loves the Father, forgetting Himself....

«This is the circular movement of each Divine ‘I’ around the other as center. They are Three, yet each regards the Others and experiences only the Others. The Father beholds only the Son, the Son only the Father, reducing [emptying] themselves reciprocally by love to the other ‘I’, to a single ‘I’. But each pair of Persons in the Trinity, reduced in this manner to One, beholds only the third Person, and thus all three Persons are reduced to One.... Whether individually or in pairs, the Persons place the other ‘I’ in the forefront, hiding themselves (as it were) beneath Him».482

Thus it can be seen how the revelation of the Triadic Oneness of God reconciles the seemingly contradictory truths about Him which had formerly been known to mankind. It now becomes possible to see how God can be one, personal, and selfless (self-forgetting) at the same time.

But why, it may be asked, are there precisely three Persons? Could there not be only two Persons in order for God to be both personal and selfless? To this Fr. Dumitru answers that perfect, objective Love could not exist if there were only two Divine Persons, for exclusive love between two persons, like self-love, can be self-absorbed and subjective – as can be observed in human experience. Perfect Love must pass on to a Third, whose existence represents the transcendence of self-absorbed duality. Fr. Dumitru writes:

«If one ‘I’ closed in on itself remains in a dreamlike subjectivity, the absorption of two ‘I’s’ into a mutual love which is indifferent towards the presence of any other also preserves, to a certain extent, this same character of dreamlike subjectivity and uncertainness of existence. This incomplete unity and lack of certainty fosters a greediness for the other in each of the Two which transforms him into an object of passion, and this is beneath the level of true love. Complete unity and the full assurance of existence are possessed by the two ‘I’s’ when they meet in a Third by virtue of their mutual love for the Third. In this way they transcend that particular subjectivity which is fraught with the danger of illusion».483

14. The Incomprehensibility of the Triad

The mystery of the Triadic One, since it has to do with the Essence of God, is ultimately incomprehensible not only to discursive reasoning, but to pure intuition as well. That is why even Lao Tzu could not come to the realization of it. Strange to say, with the mystery of the Triad revealed, man knows more about God than he ever knew before, but also realizes more fully the utter unknowability of God’s Essence.

Both Lao Tzu and the ancient Greeks spoke of the incomprehensibility of the Absolute, of its «namelessness» – which, as Gi-ming Shien observes, is also bound up with Lao Tzu’s concept of «nothingness». But while the Absolute Being of these philosophies is beyond discursive reasoning, it is not by nature incomprehensible to pure human intellection, and can be positively defined as the One. With the mystery of the Triad, the incomprehensibility of God is shown to be more radical, more absolute than either Lao Tzu or the Greeks could have known. In Of the Divine Names – a mystical work of the fifth century A.D., written in the tradition of St. Dionysius the Areopagite – the author examines the name of the One, which can be applied to God, and then compares it with another «most sublime name» – that of the Triad, which teaches us that God is ultimately neither one nor many, and is both at the same time, being unknowable in what He is.

«God is identically Monad and Triad», writes St. Maximus the Confessor († A.D. 662).484 The highest point of revelation is thus an antinomy, a paradox that cannot be resolved through human powers. Archimandrite Sophrony writes: «Our rationally functioning mind is gripped in a vice, unable to incline to one side or the other, like a figure crucified on a cross».485

What Lao Tzu called the «namelessness» of the Absolute thus finds its fulfillment in the revelation of the Triadic Oneness as primordial fact. It is ultimate reality, first datum which cannot be deduced, explained or discovered by way of any other truth; for there is nothing which is prior to it. Human thought, renouncing every support, finds its support in God. Here thought gains a stability which cannot be shaken; ignorance passes into knowledge.486

St. Gregory Nazianzen († A.D. 390), who has been called «the minstrel of the Holy Trinity», beautifully describes his contemplation of this suprarational antinomy: «No sooner do I conceive of the One than I am illumined by the splendor of the Three; no sooner do I distinguish Them than I am carried back to the One. When I think of any One of the Three, I think of Him as the whole, and my eyes are filled, and the greater part of what I am thinking of escapes me. I cannot grasp the greatness of that One so as to attribute a greater greatness to the rest. When I contemplate the Three together, I see but one torch, and cannot divide or measure out the undivided Light».487

15. Foreshadowings of the Triadic Mystery

If the mystery of the Triadic One cannot be deduced through human powers, why did not God reveal it to Moses when He revealed the mystery of «I AM»? Archimandrite Sophrony answers as follows:

«God revealed Himself insofar as Moses could apprehend, for Moses could not contain the whole revelation: ‘I will make all my goodness pass before you, and I will proclaim the name of the Lord before you... and while my glory passes by, I will cover you with my hand.... And I will take away my hand, and you shall see my back parts: but my face shall not be seen’.488

«Centuries passed before the true content of the amazing Name I AM was understood. For all the fervor of their faith neither Moses nor the prophets who were his heirs appreciated to the full the blessing bestowed on them. They experienced God mainly through historical events. If they turned to Him in spirit, they contemplated in darkness. When we, sons of the New Testament, read the Old Testament we notice how God tried to suggest to our precursors that this I AM is One Being and at the same time Three Persons. On occasions He would even speak of Himself as We. ‘And God said, Let us make man in our image, after our likeness.489 ‘And the Lord God said, Behold, man is become as one of us’490. An even more remarkable instance occurs with Abraham: three men appeared to him yet he addressed them as if they were but one».491

Here, in speaking of glimpses of the Triadic Oneness in the Old Testament, we cannot neglect to mention the startling phrase in chapter 42 of the Tao Teh Ching, in which Lao Tzu writes, «The Three produced all things». Commenting on this passage, Gi-ming Shien says that the Three represents «the reconciliation of opposites» – which is not far from St. Gregory Nazianzen’s explanation of the meaning of the Triad: «The Triad contains itself in perfection, for it is the first which surpasses the composition of the dyad».492Gi-ming Shien further stated that «the Three is the principle of order», and thus it is that it «produces all things».493Here it can be seen that Lao Tzu, although he was not given to know the full meaning of the Triad, nevertheless realized it to be a creative Principle.

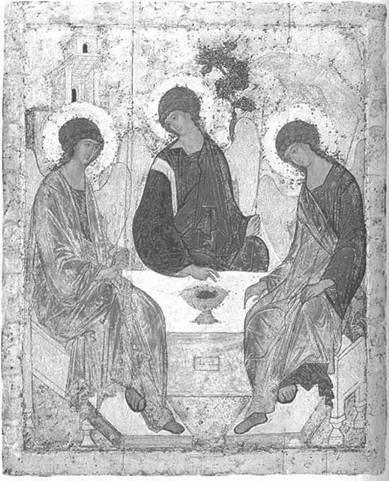

Icon of the One Triadic God appearing to Abraham in the form of three angelic visitors. The Father/Mind is represented by the angel at left, Since He is the Originating Principle of the Godhead, both the Son/Word (center) and the Spirit/Breath (right) are turned towards Him. In this mystically symbolic composition, the bodies of the Father and the Spirit form the contours of a chalice between them, with the Son in the middle of it. The chalice represents the cup of Christ’s Body and Blood, shed for the world. Thus, while the Son and the Spirit are bearing witness to the Father, the Father and the Spirit, by their very positions, are bearing witness to the Son in self-forgetting love. Russian icon painted by St. Andrew Rublev, first half of the fifteenth century.

16. The Expectation of the Ancient Hebrews

«The fact that the revelation received by Moses was incomplete », continues Archimandrite Sophrony, «is shown in his testimony to the people that ‘the Lord your God will raise up unto you a Prophet from the midst of you... unto him you shall hearken.’ Also: ‘And the Lord said unto me... I will raise them up a Prophet from among their brethren, like unto you, and will put my words in his mouth, and he shall speak unto them all that I shall command him.’494According to the Old Testament all Israel lived in expectation of the coming of the Prophet of whom ‘Moses wrote,’495‘THAT prophet.’496The Jewish people looked for the coming of the Messiah who when he was come would tell them all things.’497Come and live among us, that we may know You, was the constant cry of the ancient Hebrews. Hence the name ‘Emmanuel, which being interpreted is, God with us.’498

«The focal point of the universe and the ultimate meaning of the entire history of the world is the coming of Jesus Christ, Who did not repudiate the archetypes of the Old Testament but vindicated them, unfolding to us their real significance and bringing new dimensions to all things – infinite, eternal dimensions.

«It was given to Moses to know that Absolute Primordial Being is not some general entity, some impersonal cosmic process. It was proved to him that this Being had a personal character and was a living and life-giving God. Moses, however, did not receive a clear vision: he did not see God in Light as the Apostles saw Him on Mount Tabor – ‘Moses drew near unto the thick darkness where God was.’499... Having reached the frontier of the Promised Land, Moses died».500

THE SEAL: Three ancient Chinese names for the Divine Being: Shang Ti («Supreme Ruler»), Tao («the Way»), and Ling («Spirit»).

Created in the Da Zhuan style of 1766–221 B.C., this seal represents the Triadic mystery by means of the archaic Chinese pictographs. Here Shang Ti

corresponds to the Father/Mind (the Originating Principle of the Godhead); Tao corresponds to the Son/Word (the Operating Cause of the creation); and Ling corresponds to the Spirit/Breath (the Perfecting Cause).

Today in China, followers of Christ commonly refer to God as Shang Ti – and also as Shen, another word for «Spirit». They refer to the Holy Spirit as Sheng Ling, a combination of two ancient characters, «holy» and «spirit»

, the latter being an exact duplication of the ancient written form. And, as we have seen, they refer to the «Word» of God (as found in the Bible) as Tao. In this way they remain tied to the most primeval roots of Chinese religion even while embracing the new revelation of the incarnate Tao.

Chapter three. When the way became flesh

17. Christ as «I AM»

And so He appeared, He to Whom the world owed its creation. The Tao/Logos of the ancient Chinese and Greeks had now, in a way surpassing nature, taken the form of a man. The Messiah had come Whom the ancient Hebrews had awaited to lead them into all truth. «Christ’s new covenant», writes Fr. Sophrony, «announces the beginning of a fresh period in the history of mankind. Now the Divine sphere was reflected in the searchless grandeur of the love and humility of God, our Father. With the coming of Christ all was changed: the new revelation affected the destiny of the whole created world».501

When the Tao became man in Jesus Christ, He revealed Himself as the very I AM Who had spoken to Moses on Mount Sinai. To the Jews He said, «Your father Abraham rejoiced to see my day, and he saw it and was glad». Uncomprehending, the people asked Him, «You are not yet fifty years old, and have you seen Abraham?» Christ said to them, «Most assuredly, I say to you, before Abraham was, I AM».502When He uttered this – the most sacred name for God in the Hebrew religion – the Jews knew exactly what he was saying.503

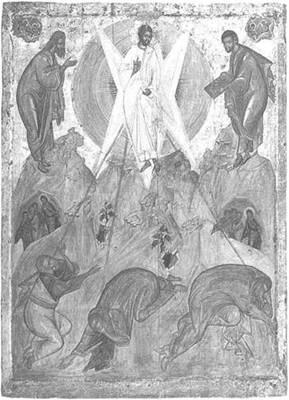

Icon of Christ transfigured on Mount Tabor, surrounded by Uncreated Light and appearing with Prophets Moses and Elijah. Below, the Apostles are falling to the ground. Russian icon by Theophanes the Greek, fifteenth century A.D.

18. The Teh of Christ

In taking flesh, the Tao united human energy with Divine Energy in one person. Divine Energy did not act upon Him, as it had upon Moses and to a lesser extent upon Lao Tzu. Rather, this was Christ’s own Energy: the Uncreated Power (Teh) of the Tao. It was by this Teh – the same Teh that Lao Tzu said nourished all creation– that Christ performed His miracles. The Gospels record that «the whole multitude sought to touch Him, for Power (Teh) went out of Him and healed them all» (Here the original Greek word for «power» is dunamis. Like the Chinese word Teh, dunamis is translated as both «power» and «virtue». The King James Bible, for example, reads: «For there went Virtue out of Him»).504When a woman touched Him and was instantly healed, Christ Himself said, «Somebody has touched me, for I perceive that Power has gone out of me».505

The people around Christ could not see this Energy. On the mountain of Tabor, however, Christ opened the spiritual eyes of His Apostles to let them see it – and they beheld it as Light: «And He was transfigured before them. His face shone like the sun, and his garments became as white as the Light».506Commenting on this supernatural event, the Romanian Orthodox priest George Calciu says, «Don’t imagine that Jesus Christ took from His Father the Uncreated Light just for that moment. He was surrounded by this Light all the time, and He only opened the eyes of the Apostles to see His Light on the Mountain of Tabor in order to make them understand that He was truly God. The Apostles were not prepared to see the Light of Jesus Christ, and because of this they fell to earth».507

19. The Christ of Lao Tzu

It is a strange yet incontrovertible fact that, when God did take flesh, He in many ways (though certainly not all) revealed Himself to be closer in spirit to the Tao of Lao Tzu than to God as conceived by the Hebrews at that time, even though the Hebrews had the revelation of Moses. This might be difficult to accept by those who are accustomed to thinking of Christ as the fulfillment of the expectation specifically of the Hebrews. Ancient Christian tradition, however, holds that Christ satisfied the longings of all the nations (The closeness of Christ to the Chinese mind is attested to by the great number of people who are turning to Christ in China today. See Appendix 1).508

Since they viewed God as dwelling in solitude, many of the Hebrew religious leaders of Christ’s time had come to regard Him as an inexorable cosmic Judge. He was the Supreme Authority who had set up a system of law and punished offenders out of personal indignation. His justice was exact. For the religious leaders, then, the law was everything and had to be followed to the letter. This idea led in later centuries to an endless codification and interpretation of religious laws.

When the Tao became flesh, He did not at all resemble this idea of God. He was, as Lao Tzu had said of Him, «like water, which greatly benefits all things but does not compete with them, dwelling in lowly places that all disdain»509. Archimandrite Sophrony writes:

«He came in utter meekness, the poorest of the poor with nowhere to lay His head. He had no authority, neither in the State nor even in the Synagogue founded on revelation from on High, He did not fight those who spurned Him. And it has been given to us to identify Him as the Pantocrator (All-powerful) precisely because He ‘made himself of no reputation, and took upon himself the form of a servant,’510 submitting finally to duress and execution. As the Creator and true Master of all that exists, He had no need of force, no need to display the power to punish opposition».511

Christ said of Himself: «The kings of the Gentiles exercise lordship over them... but I am among you as he who serves»512. Likewise, Lao Tzu had written of Him before His coming:

The Great Tao clothes and feeds all things,

Yet does not claim them as its own.

All things return to it,

Yet it claims no leadership over them.513

The ancient Hebrews knew that their Messiah would come in the form of a man. When He did come, «the common people heard Him gladly,»514 and some said, «No man ever spoke like this man».515 Others, however, especially among the leaders, rejected Him because He did not fit their preconceived image of Him. In spite of the testimony of the Prophet Isaiah who foretold that the Messiah would not so much as «break a bruised reed»,516 they expected Him to be a worldly authority figure who would raise an army and mercilessly rout their Roman oppressors. On the contrary, they saw that Christ was (in His own words) «meek and lowly in heart».517 Of Him, Lao Tzu had «prophesied»:

The Tao does not show greatness,

And is therefore truly great.

It does not contend, and yet it overcomes.518

«For the Son of man», said Christ of Himself, «is not come to destroy men’s lives, but to save them».519

Unlike the Hebrews, Lao Tzu did not live in expectation of a Messiah. And yet, as Fr. Seraphim Rose believed, he would have followed Christ if he had seen Him, for he would have recognized in Him the humble Tao which he had intuited in purity of mind.

20. Christ’s Revelation of the Triad

In revealing in His Person the selflessness of the Absolute, Christ opened to mankind the «secret» behind it – the mystery of the Triad.

If God had revealed Himself to Moses not only as «I AM» but also as «I AM THREE IN ONE», this would have meant nothing to Moses and his people. Only God Himself could contain the fullness of this mystery; therefore, only God Himself could bring the knowledge of it to mankind. By walking among us in the likeness of our flesh, He revealed the Triadic One not as a verbal or written formula, but as a living, personal Reality. Due to the awesomeness of the mystery, however, He did this only gradually.

«The acquisition of knowledge of God is a slow process», explains Fr. Sophrony, «not to be achieved in all its plenitude from the outset, though God is always and in His every manifestation invariably One and indivisible. Christ used simple language intelligible to the most ignorant, but what He said was above the heads even of the wisest of His listeners. ‘Before Abraham was, I AM.’ ‘I and my Father are one.’ ‘My Father will love him, and we will come unto him, and make our abode with him.’ ‘I will pray the Father, and He shall give you another Comforter, that He may abide with you forever.’ (So now a Third Person is introduced.) ‘The Spirit of truth, Who proceeds from the Father, He shall testify of me.’520

«We note that Christ only gradually began to speak of the Father, and it was not until towards the end of His earthly life that He spoke of the Holy Spirit. Right to the end the disciples failed to understand Him, and He made no attempt to explain to them the image of Divine Being. ‘I have yet many things to say unto you, but you cannot bear them now.’ Instead, He indicated how we might attain perfect knowledge: ‘If you continue in my word... you shall know the Truth.’ ‘The Holy Spirit... shall teach you all things, and bring to your remembrance all things that I said unto you’. ‘When He, the Spirit of Truth, has come, He will guide you into all Truth’».521

21. Christ’s Revelation of the God of Love

With Christ’s revelation of the Triad, mankind realizes for the first time that, truly, «God is love». Now it is seen how, if God were mono-Hypostatic (that is, one Person), He would not be love. Archimandrite Sophrony writes:

«Moses, who interpreted the revelation of I AM as meaning a single Person, gave his people the Law. But ‘Grace and truth came by Jesus Christ.’522The Trinity is the God of love.... Jesus, knowing ‘that His hour was come that He should depart out of this world unto the Father, having loved His own which were in the world, He loved them unto the end.’523 This is our God. And there is none other save Him. The man who by the gift of the Holy Spirit has experienced the breath of His love knows with his whole being that such love is peculiar to the Triune Godhead revealed to us as the perfect mode of Absolute Being. The mono-Hypostatic God of the Old Testament and (long after the New Testament) of the Koran does not know love.

«To love is to live for and in the beloved whose life becomes our life. Love leads to singleness of being. Thus it is within the Trinity. ‘The Father loves the Son.’524 He lives in the Son and in the Holy Spirit. The Son ‘abides in the love of the Father’525 and in the Holy Spirit. And the Holy Spirit we know as love all-perfect. The Holy Spirit proceeds eternally from the Father and lives in Him and abides in the Son. This love makes the sum total of Divine Being a single eternal Act. After the pattern of this unity, mankind must also become one man».526

Christ said, «I and my Father are one». And for His disciples He prayed, «That they all may be one; as You, Father, are in me, and I in You, that they also may be one in us».527 Christ’s commandment to love is thus a projection of heavenly love on the earthly plane. Realized in its true content, it makes the life of mankind similar to that of the Divine Triadic One.

22. Christ's Law of Love

God, in telling the Prophet Jeremiah of the new covenant that the Messiah would bring, had said, «After those days I will put my law in their inward parts, and write it in their hearts».528 When Christ came revealing the love of the Triad, he reminded man of the true purpose of the law, and raised it to a new dimension. The law was not an end in itself, nor was it for the purpose of meeting the exact requirements of an angry Judge-God. «The [law of keeping] the Sabbath was made for man», Christ explained, «and not man for the Sabbath».529

As Christ showed, the law had been given to man by the God of love, in order that man would in turn love God and his neighbor. Quoting from the very words of the law, Christ said, «You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your mind; and you shall love your neighbor as yourself. On these two commandments hang all the law and the prophets».530

Ultimately, the only law that Christ gave to man was the law of love. Having this law «in their inward parts», His followers would obey God’s law naturally, spontaneously, without always having to think, to choose, and to worry over legalistic formulas.

Just as Lao Tzu’s «superior virtue... unconscious of its virtue» is rooted in the «nothingness» of spontaneity and self-forgetting, so too is the love of which Christ spoke: «When you do a merciful deed, let not your left hand know what your right hand is doing».531

The love that Christ taught was not merely the commonplace love for ones friends, family and kinsmen. He spoke of Perfect Love – the reflection of the Divine life of the Triadic God – in which a person finds the one human nature and is thus able to love all people equally.

Having taken human form, the Tao/Logos made the Personhood of God far more tangible than ever before. In so doing, He also brought the meaning of human personhood into sharper focus than had been previously known. Just as He had brought new dimensions to the archetypes of the Old Testament, so He did to the teachings of Lao Tzu. He gave a personal dimension to Lao Tzu’s «nothingness»; and this personal dimension of self-emptying is what we call Perfect Love.

Lao Tzu understood that a person who asserts himself as an individual, far from realizing himself fully, becomes impoverished. It is only in renouncing its

possessiveness, giving itself freely and ceasing to exist for itself (i.e., being reduced to «nothingness») that the person finds full expression in the one nature common to all. In giving up its own particular advantage, it expands infinitely, and is enriched by everything which belongs to all.532 Of such a person Lao Tzu said, «His heart is immeasurable».533

Christ, in revealing the mystery of love between the Persons of the Triad, at the same time revealed the mystery of what Lao Tzu had intuited on a human level. He showed that, by acquiring the perfection of the common human nature, each person actually acquires the image of the common Divine Nature. Man has been made in God’s image. Thus, when a person experiences spiritual oneness with all people, he is in the likeness of the Triadic One: the Essence of Perfect Love.

The touchstone of this Perfect Love is love for one’s enemies. When the Tao/Logos became flesh, He brought out the full meaning of Lao Tzu’s precept, «Requite injury with kindness», speaking of it in terms of love. «Love your enemies», He taught, «do good to those who hate you, bless those who curse you, and pray for those who spitefully use you. Give to everyone who asks you; and of him who takes away your goods ask them not again. Judge not, and you shall not be judged. Condemn not, and you shall not be condemned. Forgive, and you will be forgiven. Give, and it will be given to you: good measure, pressed down, and shaken together, and running over will be put into your bosom».534

23. Christ’s Revelation of the Selflessness of the Tao

Christ’s selflessness or «nothingness», as we have said, was based in His Divine life within the Triad. During His life on earth, this was seen first of all in His total self-renunciation before the Father. He renounced His will in order to accomplish the will of the Father by being obedient to Him.

In speaking of Christ’s obedience to the Father, we must be careful not to think too much in human terms. For Christ, the renunciation of His own will was not a choice or an act; it was spontaneous, for renunciation is the very being of the Triad, Who have only one will proper to their common nature. The Divine will in Christ was the will common to the Three. That is why Christ could say, «He who has seen me has seen the Father».535

Self-emptying is the very mode of existence of the Tao Who was sent into the world. Christ’s saying, «My Father is greater than I»,536 expresses this emptying of His own will. «My Father has been working until now», He said, «and I have been working.... The Son can do nothing of Himself, but what He sees the Father do: for whatever He does, the Son also does likewise. For the Father loves the Son, and shows Him all things that He Himself does.... For as the Father raises up the dead and gives life to them, even so the Son gives life whom He will».537 Here it is seen that the work accomplished on earth by Christ is the common work of the Triad, for He shares the same Essence with the Father and the Spirit. The outpouring, self-emptying of Christ only produces the greater manifestation of His Divinity to all those who are able to recognize greatness in abasement, wealth in spoliation, and liberty in obedience.538

The very fact that Christ the Tao/Logos was «sent into the world»539 by the Father shows His obedience to Him, when He emptied Himself into His own creation by taking on human flesh subject to death. In doing His Father’s will throughout His earthly life, He endured mockery, opposition, and persecution at every turn. This culminated in the ultimate self-emptying of undergoing the most humiliating and painful death known at the time: being scourged, stripped naked, and crucified in public view.

The Apostle Paul sums up the whole act of the Tao’s self-emptying in Christ: «He emptied Himself, taking the form of a servant, being born in the likeness of men. And being found in appearance as a man, He humbled Himself and became obedient unto death, even the death of the Cross».540

If Lao Tzu had known that the Tao, «which dwells in lowly places that all disdain», would one day take the form of a man, he could have conceived of no greater self-emptying, no greater lowliness, no greater «nothingness» than the incarnate Tao being nailed to a Cross and dying in a body that would rise again.

Fr. Seraphim Rose once wrote that «nothingness», in the meaning that Lao Tzu gives it, is the «point of convergence» or axis of the universe.541 This recalls Lao Tzu’s words:

Thirty spokes join in a single hub;

It is the center hole (the space where there is nothing) that makes the wheel useful.542

If nothingness or self-emptying is the axis of the universe, then the Cross of Christ, the greatest sign to man of the self-emptying of God, now becomes that axis. Christ the Tao/Logos stands at the axis; and there, in the «space where there is nothing», we find not an impersonal void, but the personal heart of the selfless, self-forgetting God.

* * *

St. Gregory of Sinai, in The Philokalia, vol. 4, p. 222. Fr. Seraphim Rose, Genesis, Creation, and Early Man, pp. 396–98.

St. Gregory Palamas, in The Philokalia, vol. 4, p. 377.

Cf. Genesis 1:26.

St. Macarius of Egypt, in The Philokalia, vol. 3, p. 300. St. Gregory Palamas, in Tire Philokalia, vol. 4, p. 296. Cf. Romans 5:12.

St. Macarius of Egypt, in The Philokalia, vol. 3, p. 300.

St. Mark the Ascetic, in The Philokalia, vol. 1, p. 117.

Mircea Eliade, A History of Religious Ideas, vol. 1, p. 88.

John Ross, D.D., The Original Religion of China, pp. 23, 25.

See, for example, Bernhard Karlgren, tr., The Book of Documents (Shu Ching), p. 48. On how T’ien and Shang Ti were used to designate the same supreme Deity, see James Legge, The Religions of China, p. 10.

Karlgren, tr., The Book of Documents (Shu Ching), pp. 59, 73.