St. Gregory Palamas Capita 150

(Τοῦ αὐτοῦ μακαριωτάτου ἀρχιεπισκόπου Θεσσαλονίκης Γρηγορίου)

Κεφάλαια ἑκατόν πεντήκοντα φυσικά και θεολογικά, ἠθικά τε και πρακτικά και καθαρτικά τῆς Βαρλααμίτιδος λύμης

Ἧρχθαι τόν κόσμον και ἡ φύσις διδάσκει και ἡ ἰστορία πιστοῦται, και τῶν τεχνῶν αἱ εὑρέσεις και τῶν νόμων αἱ θέσεις και τῶν πολιτειῶν αἱ χρήσεις ἐναργῶς παριστᾶσι . σχεδόν γάρ τεχνῶν ἀπασῶν ἴσμεν τούς εὐρετάς και τούς νομοθέτας τῶν νόμων και τούς τήν ἀρχήν κεχρημένους τα ς πολιτείαις. ἔτι γε μήν και τῶν συγγραωαμένων περί ὁτουδήποτε τήν ἀρχήν ἀπάντων, και οὑδένα τούτων ὁρῶμεν ὑπερβαίνοντα τήν τοῦ κόσμου και τοῦ χρόνου γένεσιν, ἣν ἱστόρησεν ὁ Μωϋσῆς, ὁ τήν ἀρχήν τῆς τοῦ κόσμου γενέσεως συγγραψάμενος, διά τοσούτων ἔργων και λόγων ἐξαισίων ἀναντιρρήτους παρέσχετο παρέσχετο πίστεις τῆς καθ' ἑαυτόν ἀληθείας, ὡς σχεδόν ἃπαν γένος ἀνθρώπων καταπειθές ἐξειργάσθαι και καταγελᾶν ἀναπεῖσαι τῶν τἀνατία σοφισαμένων. ἐπεί και ἡ τοῦ κόσμου τούτου φύσις ἀεί προσφάτου τῆς καθ΄ ἓκαστον ἀρχῆς δεομένη και χωρίς αὐτῆς μηδαμῇ συνίστασθαι δυναμένη, τήν πρώτην ἑαυτῆς, ἣτις οὐκ ἐξ ἄλλης ἦν. ἀρχήν. δι΄ αὐτῶν παρίστησι τῶν πραγμάτων.

Gregory, the Most Blessed Archbishop of Thessalonica

One Hundred and Fifty Chapters On Topics of Natural and Theological Science, the Moral and the Ascetic Life, Intended as a Purge for the Barlaamite Corruption

1. That the world had a beginning both nature teaches and history confirms; the discovery of the arts, the introduction of laws and the governance of states also clearly affirm this. For we know the founders of almost all the arts, those who established the laws, and those who first administered the states. Furthermore, we see none of the first writers on any subject whatever surpassing the account of the beginning of the world and of time, as Moses recorded it.207 And Moses himself, who described the beginning of the generation of the world, provided irrefutable proofs of his veracity through such extraordinary words and deeds that he convinced virtually every race of men and persuaded them to deride the sophists who have argued the contrary. Since the nature of this world is such that it always requires a new cause in each instance and since without this cause it cannot exist at all, we have in these facts proof for an underived, self-existent primordial cause.

2. The nature of the contingent existence of realities in the world proves not only that the world has had a beginning but also that it will have an end, as it is continually coming to an end in part. Sure and irrefutable proof is also provided by the prophecy of Christ, God over all, and of other men inspired by God,208 whom not only the pious but also the impious must believe as truthful, when they see that they are right also in all the other things which they have predicted. From these men we can learn that this world will not in its entirety return to utter non-being, but, like our bodies and in a manner that might be considered analogous, the world at the moment of its dissolution and transformation will be changed into something more divine by the power of the Spirit.209

3. The Hellene sages say that the heaven revolves by the nature of the World Soul and that it teaches justice and reason.210 What sort of justice? What reason? For if the heaven revolves not by its own nature but by the nature of what they call the World Soul, and if the World Soul belongs to the entire world, why does the earth not revolve too, and the water, and the air? But yet, although in their opinion the soul is ever-moving,211 by its own proper nature the earth is stationary with the water taking up the lower region;212 likewise the heaven too by its own nature is ever-moving in a circular motion, while occupying the upper region. Whatever sort of thing is the World Soul by whose nature the heaven moves? Is it rational? Then it would be self-determining and it would not move the celestial body in the same perpetual movements, for self-determining bodies move differently at different times. And also, what trace of a rational soul do we see in this lowest sphere, I repeat, of the earth, or in the most proximate parts about it, namely, those of water and air, or even fire itself, for the World Soul belongs also to these? Furthermore, why according to them are some things animate and others inanimate?213 And these are not things taken at random, but every stone, every metal, all earth, water, air, fire; for they say that fire too is moved by its own nature and not by a soul.214 If then the soul is universal, why is the heaven alone moved by the nature of this soul but not by its own nature? But how is the soul not rational which according to them moves the celestial body, if indeed the same soul according to them is the source of our souls? But if it were not rational, it would be sensible or vegetative. But we see no soul of any kind moving a body without organs and we see no member serving as an organ, either for the earth, or for the heavens, or for any other of the elements in them, since any organ is composed of different natures, but each of the elements and also the heaven especially consists of a simple nature.215 «The soul then is the actuality of a body possessed of organs and having the potentiality for life.»216 But since the heaven has no member or part to serve as an organ, it has no potentiality for life. How then could that which is incapable of life ever possess a soul? «But those who became foolish in their reasonings» have fashioned «out of their senseless hearts»217 a soul which neither exists, has existed, or will exist. And this they proclaim the Creator, the guide and the controller of the entire sensible world, and of our souls, or rather, all souls, like some sort of root and source which has its generation from mind. And that so-called mind they say is other in substance than the highest one whom they call God.218 The most advanced in wisdom and theology among them teach doctrines such as these. They are no better than those who deify beasts and stones; rather they are much worse in their cult, for beasts and gold and stone and bronze are real, though they are among the least of creatures, but the star-bearing World Soul neither exists nor possesses reality, for it is nothing at all but the invention of an evil mind.219

4. Since, they say, the celestial body must be in motion but there is no further place to which it might proceed, it turns back upon itself and its advance is a revolving motion.220 Well enough, Then, if there were a place, it would be borne upwards just as fire is and even more so than fire itself, since it is naturally still lighter than fire.221 But this movement belongs not to the nature of a soul but to the nature of lightness. If then the advance of the heaven is a revolving motion, and if it possesses this by its own nature but not by the nature of the soul, the celestial body, therefore, revolves not by the nature of the soul but by its own nature. Thus, it does not have a soul, nor does there exist any heavenly or pancosmic soul; rather, the only rational soul is the human one, which is not celestial but supercelestial, not because of its location but by its own nature, inasmuch as it is an intelligent substance.222

5. The celestial body has no forward movement and extension upwards. The reason for this is not that there is no further place beyond, for even the adjacent sphere of aether enclosed within it does not proceed upwards. It is not because there is no place to which it might proceed, for the celestial expanse embraces this sphere of aether. It does not extend further upwards, since this upper region beyond the aether is lighter than it. And so, the celestial body is higher than the aether by its own nature.223 Thus, it is not because it has no place higher than itself that the heaven does not proceed upwards, but because there is no body more rarefied or lighter than it.

6. No body is higher than the celestial body. But if is not for this reason that the region beyond is not capable of admitting a body, but because the heaven encompasses all body and there is no other body beyond.224 But if it were possible to pass through the heaven, as is our pious belief, that region beyond the heaven would not be without access. For the God ‘who fills all things’225 and extends infinitely beyond the heaven existed even before the world, filling even as now he fills every place in the world. And this in no way resulted in there being a body in him. Therefore, there will be no obstacle to the absence of any kind of place outside of the heaven which surrounds the world or is in the world with the result being the presence of a body in God.

Since there is no hindrance, why then is the movement of the celestial body not directed upwards but rather turns back upon itself in a circular motion? Because it is located at the top as the most rarefied of all bodies, it is the highest body of all226 and also the most mobile. For just as that which is compressed to the utmost degree and most heavy is lowest and at the same time most stable, so that which is very low in density and most light is highest and at the same time most mobile.227 Thus, since it moves while located on the upper surface by nature, and since, owing to its own nature, the body in this upper location cannot be separated from the surface on which it is located, and since the regions on which the celestial body is located are spherical, it necessarily runs around these without ceasing,228 not by the nature of a soul but by its own proper nature as a body.229 (This must be the case,) since it changes in part from place to place, which is the movement most proper to bodies, just as the opposing state is most proper to the opposite bodies.

You should note also in the proximate regions about us the winds which are naturally situated at the top, moving about these regions without being separated but in no way proceeding further upwards, not because there is no place but because the regions beyond the winds are lighter than they. They remain in the regions where they are situated at the surface, inasmuch as they are lighter in nature than these. And the winds move around these regions, not by the nature of a soul but by their own nature. And I think, Solomon, wise in all things, wishing to indicate this partial likeness, gave the celestial body the same name as the winds when he wrote about this: «The wind proceeds round in circles and on its circuits the wind returns.»230 The nature of the winds surrounding us is as different from that of the upper regions and their very rapid movement, as it is distinct also from their lightness.

9. According to the Hellene sages, there are two opposing temperate and habitable zones on the earth, and when each of these is divided into two inhabited regions they produce four.231 And so, they assert that there are also four races of men on earth, which are unable to cross over to one another. For according to them there are those inhabiting the opposing temperate region on our flank, who are separated from us by the torrid zone of the earth. And dwelling opposite the people just mentioned are those who live, from their viewpoint, below this zone of ours; just as among those who are in identical relation to us, they say some are opposite and some are antipodal and reversed in relation to us. For they were unaware that except for a tenth part of the terrestrial sphere almost all the rest is inundated by the abyss of the waters.

10. You should know that apart from the region we inhabit there is no other habitable part of the earth, since it is inundated by the abyss, that is, if you bear in mind that the four elements which make up the world stand in equal proportion, and that in proportion to its proper density each of these occupies its own extent of the sphere to a much greater degree than the other,232 as Aristotle also agrees. «For there are five elements,» he says, «located in five spherical regions, the lesser element always being encompassed by the greater, earth by water, water by air, air by fire, fire by aether, and this constitutes the world.»233

11. Aether then is very much brighter than fire, which is also called combustible fuel,234 and fire is many times greater in volume than the sphere of air, and air in turn more than water, and water more than earth, which, as it is the most compressed, is the least in volume among the four elements under the heaven. Since the sphere of water is many times greater in magnitude than the earth, if it bad been spread around the entire circumference of the earth so that both spheres (namely, earth and water) were drawn around one centre, the water would not allow the use of any part of the earth to land animals, for the water would cover all its ground area and extend in great measure beyond its entire surface. But since it does not encompass the entire surface of the earth (for the dry land of the region we inhabit is not covered), the sphere of water must necessarily be eccentric. Therefore, we must ascertain how eccentric it would be and where the centre would be, whether below or above us. But being above us is impossible, for we see the surface of the water in part below us. In relation to us then the centre of the sphere of water lies below even the centre of the earth itself. But we must still ascertain how far this centre is from the centre of the earth.

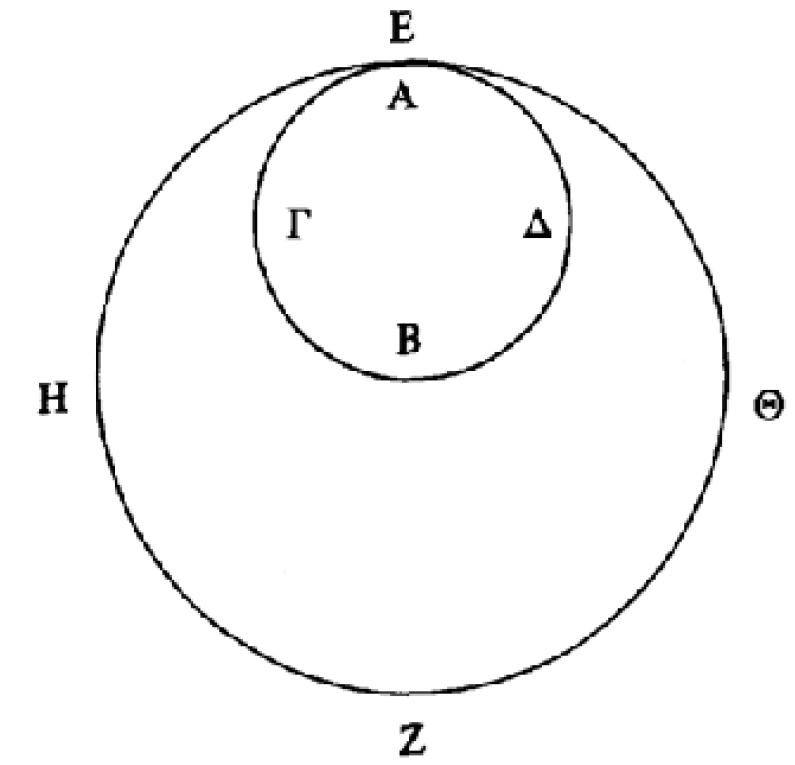

12. You should know how far below (from our viewpoint) the centre of the earth lies the centre of the sphere of water, if you bear in mind that the surface of the water visible to us and beneath us, just as the ground of the earth we walk upon, coincides almost exactly with the surface of the terrestrial sphere which we inhabit. Our habitable portion of the earth is about a tenth of its circumference, for the earth has five zones, and a half of one of these five is inhabited by us. If then you should wish to fit a sphere around the earth onto this tenth part of the surface, you will find that the diameter of the exterior sphere which encompasses also the interior one is almost twice that of the latter, and that the exterior sphere is eight times greater in magnitude, with its centre at what seems to us the lowest extremity of the earth. This is clear from the diagram.

13. Let the sphere of the earth be a circle on the inside of which is written A B Γ Δ, and around this let there be described, in place of the sphere of water, another circle coinciding along the surface with the upper tenth of the circle within it on which is inscribed E Z H Θ. Now, below us the extremity of the inner circle will be found to be the centre of the circle described on the outside. And since the latter is twice the former in diameter, and since there are geometric proofs to show that the sphere with twice the diameter is eight times the size of the sphere with half the diameter,235 it follows then that the eighth part of this moist sphere is merged with the earth. And so, a great many springs burst up from it and abundant, ever-flowing river streams issue forth, and the gulfs of not a few seas pour into it, and a multitude of marsh waters seep upwards. And there is scarcely anywhere on earth where you can dig and not find water welling up.

14. Both the diagram and the argument prove that besides the world-region we live in there is no other. For if there were the same centre for both earth and water, the entire earth would be completely uninhabitable. Likewise, even more truly, if the water has as its centre the extremity of the earth furthest below us, apart from the region where we live which fits into the upper part of that sphere, no other part can possibly be inhabited, because they are all awash in water. And it has already been proved that the embodied rational soul is found in the only inhabited region of the earth, which by the fact that it is one and the same as ours alone now constitutes additional proof. It follows then that among the irrational beasts the land animals dwell solely in this region.

15. Sight is formed from the manifold dispositions of colours and shapes, smell from odours, taste from flavours, hearing from sounds, touch from things rough or smooth according to position.236 The formations that occur in the senses arise from bodies but are not bodies though corporeal, for they do not arise from bodies in an absolute sense, but rather from the forms which are associated with bodies. They are not themselves the forms of bodies but the impressions left by the forms, like images inseparably separate from the forms associated with bodies. This is more evident in the case of vision and especially in the case of objects seen in mirrors.

16. The imaginative faculty of the soul, which in turn appropriates these sense impressions from the senses, completely separates not the senses themselves but what we have called the images in them from the bodies and their forms. And it holds them stored there like treasures, bringing them forward interiorly for its own use, one after another, each in its own time, even when a body is absent;237 and it presents to itself all manner of things, objects of sight, hearing, taste, smell and touch.

17. This imaginative faculty of the soul in the rational animal constitutes an intermediary between the mind and the senses. For when the mind beholds and dwells upon the images received within itself from the senses as separated from bodies and already incorporeal, it formulates thoughts in various ways by distinctions, analyses and syntheses. This happens in different ways: with and without passion and somewhere between passion and apatheia, both with and without error. And these are the situations from which are born most virtues and vices, as well as both good and evil opinions.238 Since not every thought comes to the mind from these and concerns these, but you could find some things which cannot fall under the observation of the senses since they are passed on to thought by the mind, for this reason I said that in thoughts not every truth or error, virtue or vice has its origin in the imagination.

18. It is a great wonder and worthy of consideration, how beauty or ugliness, wealth or poverty, honour or dishonour, and, in a word, either the intelligible light which grants eternal life239 or the intelligible darkness of chastisement becomes fixed in the soul through transitory and sensible things.

19. When the mind lingers over the imaginative faculty of the soul and thereby becomes associated with the senses, it produces a composite knowledge. For on the basis of sense perception, imagination and intellection you could arrive at an understanding that the moon gets its light from the sun, and that the moon's orbit is quite near the earth and is much below that of the sun: that is, if you should gaze with your senses at the moon which follows upon the setting sun and which is illuminated in that small part which is turned towards the sun and which then recedes little by little in the following days and is illuminated to a greater extent until the process becomes reversed, and in turn, as the moon little by little draws near the other part, it gradually diminishes in its light and moves away from the place where it originally received illumination.240 These sights you examine through the mind, in that you have previous ones in the imagination and the one which is always present to the senses.

20. We know not only the phenomena of the moon but also those of the sun, both the solar eclipses and their nodes, the parallaxes of the other celestial planets and the distances separating them and the manifold configurations formed thereby, and the phenomena of the heavens in general. And further, the laws of nature and all its methods and arts, and in general all knowledge of anything collected from perception of particulars, we have gathered together from the senses and the imagination through the mind, and no such knowledge could ever be called spiritual but rather natural, which does not attain the things of the Spirit.

21. Where can we learn anything certain and free from deceit about God, about the world as a whole, about our own selves? Is it not from the teaching of the Spirit? For this teaching has taught us that God alone is true being, eternal being and immutable being, that he neither received being out of non-being nor returns to non-being, and that he is trihypostatic and omnipotent. In six days he brought forth beings from non-being by a word, or rather, as Moses says, he established everything at once, for we have heard him say, «In the beginning God created heaven and earth»;241 not absolutely void nor without any intermediary bodies at all, for the earth was mixed with water and each was pregnant with air, and with animals and plants according to their species, while the heaven was pregnant with the various lights and fires in winch he established the universe.242 In this way then God created heaven and earth in the beginning as a sort of all-containing receptacle of matter, bearing all things in potency.243 Thereby, he rightly drives far off those who wrongly hold that matter preexisted of itself.

22. Afterwards, embellishing even as he adorns the world, the one who brought forth all things from nothing allotted in six days the proper and appropriate order to each of those which are his and make up his world. He distinguished each by command alone and brought forth into form as from hidden treasuries the things stored therein, disposing and arranging them in harmony, excellence and aptness, one to the other, each to all and all to each. With the immovable earth as a centre-point he arranged the ever-moving heaven in a circle in the uttermost heights and bound the two together with great wisdom through the middle regions. And so, the same world continues to be both stationary and mobile at the same time. For since the bodies in very rapid and perpetual motion have been arranged all in a circle, the immovable body necessarily had to occupy the middle region as its portion, counterbalancing the motion with its stability, so that the pancosmic sphere would not change position as a cylinder does.244

23. Thus, after assigning such positions to each of the two bounds of the universe, the master craftsman245 both fixed and set in motion this entire, orderly world order, so to speak, and to each of the bodies between these bounds he in turn allotted what was fitting. Some bodies he positioned above and enjoined them to move about in the upper regions and to revolve round the uppermost, boundary of the universe in a constant and right orderly fashion for all time. These are the light and active bodies which transform substances into what is useful. Quite understandably, they are situated so far above the middle region that, flaming all round, they are able to break down sufficiently the excess of cold there and restrain in its place their own excess of heat. Somehow they stay also the excessive motion of the uppermost bounds because they have their own opposing movement and they hold those bodies in place by their opposing rotation, providing us with the beneficial, yearly changes of season, the measures of temporal extension, and to the wise the knowledge of God who created, ordered and adorned the world.246 Thus, for a twofold purpose did he permit some bodies to dance round in the upper air in fast rotation, namely, for the sake of the beauty of the universe and for manifold benefit. Other bodies he set below around the middle region. These possess weight, are passible in nature and naturally come into being and change, decomposing and coming together again, or rather, they are able to change to a useful purpose. He established these things and their proportion to one another in due order so that the All may truly be called Cosmos.

24. Thus was the first of beings brought forth in creation and after the first another and after that still another, and so forth, and after all things man. He was deemed worthy by God of such honour and providential care that before him this entire sensible world came into being for his sake, and before him right from the foundation of the world the kingdom of heaven was prepared for his sake247 and counsel concerning him was taken beforehand248 and he was formed by the hand of God and according to the image of God. He did not derive everything from this matter and the sensible world like the other animals but the body only; the soul he derived from the realities beyond the world, or rather, from God himself through an ineffable insufflation,249 like some great and marvellous creation, superior to the universe, overseeing the universe and set over all creatures, capable of both knowing and receiving God, and, more than any, capable of manifesting the exceeding greatness of the Artificer; and not only is the human soul capable of receiving God through struggle and grace, but also it was able to be united with God in a single hypostasis.250

25. Here and in such things lie the true wisdom and the saving knowledge which procure blessedness on high. What Euclid, what Marinos, what Ptolemy could understand? What Empedocleans, Socratics, Aristotelians or Platonists with their logical methods and mathematical proofs?251 Or rather, what sort of sense perception has grasped such things? What mind apprehended them? If the spiritual wisdom seemed earthbound to those natural philosophers and their followers, consequently the one who stands supereminently superior to it turns out also to be such. For almost as the irrational animals are related to the wisdom of those men (or, if you wish, like little children for whom the pancakes they have at hand would seem superior to the imperial crown, or even to everything known by those philosophers), just so are these philosophers to the true and most excellent wisdom and teaching of the Spirit.

26. Knowing God in truth to the extent that this is possible is not only incomparably better than Hellenic philosophy, but also, knowing what place man has before Cod, alone of itself, surpasses all their wisdom.252 For of all earthly and heavenly things man alone was created in the image of his Maker, so that he might look in him and love him, and that he might be an initiate and worshipper of God alone and might preserve his proper beauty by faith in him and inclination and disposition towards him, and that he might know that all other things which this heaven and earth bear are inferior to himself and completely devoid of intelligence. Since the Hellenic sages have not been able to understand this at all, they have dishonoured our own nature and acted impiously towards God; «They worshipped and served the creature rather than the Creator,»253 endowing the sense-perceptible and insensate stars with intelligence, in each case proportionate in power and rank to its corporeal magnitude. And worshipping these in their sorry manner, they address them as superior and inferior gods and entrust them with dominion over the universe. On the basis of sensible things and philosophy on such have these men not inflicted shame, dishonour and the ultimate penury on their own souls, and also the verily intelligible darkness of punishment?

27. The knowledge that we are made in the image of the Creator does not permit us to deify even the intelligible world, for it is not the bodily constitution but the very nature of the mind which possesses this image and nothing in our nature is superior to the mind. If there were something superior, that is where the image would be. But since our superior part is the mind – and even though this is in the divine image, it was nevertheless created by God -, why then is it difficult to understand, or rather, how can it not be self-evident that the maker of our intellectual being is also the maker of all intellectual being? Therefore, every intellectual nature is a fellow servant with us and is in the image of the Creator, even though they be more worthy of honour than we because they are without bodies and are nearer to the utterly incorporeal and uncreated nature. Or rather, those among them who kept to their proper rank and longed for the goal of their being, even though they are fellow servants, are honoured by us and because of their rank are much more worthy of honour than we are. But those who did not keep to their rank but rebelled and denied the goal of their being have become utterly alienated from those who are near God and they have fallen from honour. But if they try to draw us too towards a fall, they are not only worthless and without honour but also opposed to God and harmful and most hostile to our race.

28. But natural scientists, astronomers, and those who boast of knowing everything have been unable to understand any of the things just mentioned on the basis of their philosophy and have considered the ruler of the intelligible darkness and all the rebellious powers under him not only superior to themselves but even gods and they honoured them with temples, offered them sacrifices, and submitted themselves to their most destructive oracles by which they were fittingly much deluded through unholy holy things and defiling purifications, through those who inspire abominable presumption and through prophets and prophetesses who lead them very far astray from the real truth.

29. Not only are man's knowledge of God and his understanding of himself and his proper rank (which knowledge now belongs to those who are Christians, even those considered uneducated laymen) a more lofty knowledge than natural science and astronomy and any philosophy in these subjects, but also our mind's knowledge of its own weakness and the search for its healing would be incomparably superior by far to the investigation and knowledge of the magnitudes of the stars and the reasons for natural phenomena, the origins of things below and the circuits of things above, their changes and risings, their fixed positions and retrograde motions, their disjunctions and conjunctions, and, in general, the entire multiform relation that results from their considerable motion in that region. For the mind that realizes its own weakness has discovered whence it might enter upon salvation and draw near in the light of knowledge and receive true wisdom which does not pass away with this age.

30. Every rational and intellectual nature, whether you should call it angelic or human, possesses life essentially, whereby it subsequently perdures as immortal in its existence and incapable of destruction. But our rational and intellectual nature possesses life not only essentially but also as an activity, for it gives life even to the body joined to it. And so, life might be predicated of the body as well. And whenever life is predicated of the body, this life is so predicated as dependent upon something else and is an activity of that substance, for as dependent upon something else life could never be called a substance in itself. The intellectual nature of the angels, on the other hand, does not possess life as an activity of this sort, for it did not receive from God an earthly body joined to it, so as to receive in addition a life-giving power for this purpose. However, it is susceptible of opposites, namely, good and evil. The evil angels confirm this in that they experienced a fall because of their pride. Thus, in a sense, even the angels are composite on the basis of their own substance and one of the opposing qualities, I mean virtue and vice. And so, not even these are shown to possess goodness essentially.

31. The soul of each of the irrational animals constitutes the life for the body it animates and so animals possess life not essentially but as an activity, since this life is dependent on something else and is not self-subsistent. For the soul is seen to possess nothing other than the activities operated through the body, wherefore the soul is necessarily dissolved together with the passing of the body. The soul is no less mortal than the body, since everything which it is relates and refers to mortality, and so it dies when the body does.

32. The soul of each man is also the life of the body it animates, and it possesses a life-giving activity seen as directed towards something else, namely, to the body which it vivifies. But the soul possesses life not only as an activity but also essentially, since it lives in its own right, for it is seen to possess a rational and intellectual life which is manifestly distinct from that of the body and its corporeal phenomena. For that reason, when the body passes away, the soul does not perish with it. In addition to the fact that it does not perish with the body, the soul also perdures immortally, since it is not seen as directed towards another but possesses life essentially of itself.

33. The rational and intellectual soul possesses lift essentially but is susceptible of opposites, namely, good and evil. Whence it is shown not to possess goodness essentially, just as it does not possess evil in this way, but as a sort of quality, being disposed according to either one, whenever it might be present. The quality is not spatially located, but rather it is present when the intellectual soul, having received free will from the Creator, inclines towards the quality and wills to live in accordance with it. Thus the rational and intellectual soul is composite in a sense, but not on the basis of the above-mentioned activity, for since that activity is directed towards something else it does not naturally produce composition; but rather on the basis of its own substance and of whichever one of the just mentioned opposite qualities, I mean virtue and vice.

34. The supreme mind, the highest good, the nature possessed of supernal life and divinity,254 since it is utterly and absolutely incapable of admitting contraries, manifestly possesses goodness not as a quality but as a substance.255 Therefore, any particular good that one might conceive of is found in it, or rather, the supreme mind is both that good and beyond it. And anything in the supreme mind that one might conceive of is a good, or rather, goodness and a goodness which transcends itself.256 Life too is found in it; or rather, the supreme mind is itself life, for life is a good and life in it is goodness. Wisdom too is found in it; or rather, it is itself wisdom, for wisdom is a good and wisdom in it is goodness; and similarly with eternity and blessedness and in general any good that one might conceive of.257 And there is no distinction there between life and wisdom and goodness and the like, for that goodness embraces all things collectively, unitively and in utter simplicity;258 and it is subject to both thought and expression on the basis of all good things. It is both one and true, which are good things that one might both conceive and say concerning it. But that goodness is not only identical with that which is truly conceived by those who think with a mind endowed with divine wisdom and speak of God with a tongue moved by the Spirit;259 as ineffable and inconceivable, it is also beyond these things, and is not inferior to the unitive and supernatural simplicity, in that the absolute and transcendent goodness is one. For according to this fact alone, namely, that he is absolute and transcendent goodness possessing goodness substantially, the Creator and Lord of creation is subject to both thought and expression and, in this, only on the basis of those of his energies which are directed towards creation. Therefore, he is utterly and absolutely incapable of admitting contrariety in this respect, for no substance possesses a contrary.

35. This absolute and transcendent goodness is itself also the source of goodness, for this too is a good and the highest of goods, and it could not be lacking in perfect goodness.260 Since the transcendently and absolutely perfect goodness is mind, what else but a word could ever proceed from it as from a source?261 But it is not a word in the sense we use of a word expressed orally, for that does not belong to the mind but to the body moved by the mind. Nor is it in the sense we use of a word immanent in us, for that too is so disposed within us to correspond to types of sounds. But nor is it in the sense of a word in our discursive intellect, even though it be without sounds and is produced entirely by incorporeal mental impulses, for that too is posterior to us and requires both intervals and not a few extensions of time since it comes forth gradually and is brought from incompletion in the beginning towards its completion in the end. Rather, it is in the sense of the word naturally stored up within our mind, whereby we have come into being from the one who created us according to his own image, namely, that knowledge which is always coexistent with the mind. The knowledge also present there in a special way in the supreme mind of the absolutely and transcendently perfect goodness, in which there is nothing imperfect except that this knowledge is derived from it, is indistinguishably all things that goodness is. Therefore, the supreme Word is also the Son and is so named by us, in order that we may recognize him as being perfect in a perfect and proper hypostasis,262 since he is derived from the Father and is in no way inferior to the Father's substance but is indistinguishably identical with him, though not in hypostasis, which indicates that the Word is derived from him by generation in a divinely fitting manner.

36. Since the goodness which proceeds by generation from intellectual goodness as from a source is the Word, and since no intelligent person could conceive of a word without spirit, for this reason the Word, God from God, possesses also the Holy Spirit proceeding together with him from the Father. But this is spirit not in the sense of the breath which accompanies the word passing through our lips (for this is a body and is adapted to our word through bodily organs); nor is it spirit in the sense of that which accompanies the immanent and the discursive word within us, even though it does so incorporeally, for that too entails a certain motion of the mind which involves a temporal extension in conjunction with our word and requires the same intervals and proceeds from incomplete on to completion. But that Spirit of the supreme Word is like an ineffable love of the Begetter towards the ineffably begotten Word himself. The beloved Word and Son of the Father also experiences this love towards the Begetter, but he does so inasmuch as he possesses this love as proceeding from the Father together with him and as resting connaturally in him.263 From the Word who held concourse with us through the flesh we have learned also the name of the Spirit's distinct mode of coming to be from the Father, and that the Spirit belongs not only to the Father but also to the Son. For he says, «The Spirit of Truth, who proceeds from the Father,»264 in order that we may recognize not a Word alone but also a Spirit from the Father, who is not begotten but who proceeds, but he belongs also to the Son who possesses him from the Father as Spirit of truth, wisdom and word. For truth and wisdom constitute a word appropriate to the Begetter, a Word which rejoices together with the Father who rejoices in him, according to what he said through Solomon, «I was the one (i.e., Wisdom) who rejoiced together with him.»265 He did not say «rejoiced» but «rejoiced together with,» for this pre-eternal joy of the Father and the Son is the Holy Spirit in that he is common to them by mutual intimacy.266 Therefore, he is sent to the worthy from both, but in his coming to be he belongs to the Father alone and thus he also proceeds from him alone in his manner of coming to be.

37. Our mind too, since it is created in the image of God, possesses the image of this highest love in the relation of the mind to the knowledge which exists perpetually from it and in it, in that this love is from it and in it and proceeds from it together with the innermost word. The insatiable desire of men for knowledge is a very clear indication of this even for those who are unable to perceive their own innermost being. But in that archetype, in that absolutely and supremely perfect goodness wherein there is no imperfection, leaving aside the being derived from it,267 the divine love is indistinguishably identical in every way with that goodness. Therefore, this love is the Holy Spirit and another (name for the) Paraclete and is so called by us, since he accompanies the Word, in order that we may recognize him as perfect in a perfect and proper hypostasis, in no way inferior to the substance of the Father but being indistinguishably identical with both the Son and the Father, though not in hypostasis – a fact which indicates to us that he is derived from the Father by way of procession in a divinely fitting manner – and in order that we may revere one true and perfect God in three true and perfect hypostases, certainly not threefold, but simple. For goodness is not something threefold nor a triad of goodnesses; rather, the supreme goodness is a holy, august and venerable Trinity flowing forth from itself into itself without change and abiding with itself before the ages in divinely fitting manner, being both unbounded and bounded by itself alone, while setting bounds for all things, transcending all things and allowing no beings independent of itself.

38. On the one hand, then, the intellectual and rational nature of the angels also possesses mind, and word from the mind, and the love of the mind for the word, which love is also from the mind and ever coexists with the word and the mind, and which could be called spirit since it accompanies the word by nature. But the angelic nature does not possess this spirit as life-giving, for it has not received from God an earthly body joined with it in order that it might receive also a life-giving and conserving power for this purpose. But, on the other hand, the intellectual and rational nature of the soul, since it was created in conjunction with an earthly body, received this spirit from God as also life-giving, through which it conserves and gives life to the body joined to it. Thereby, it is shown to men of understanding that man's spirit, the life-giving power in his body, is intellectual love; it is from the mind and the word, and exists in the word and the mind, and possesses both the word and the mind within itself. Through it the soul naturally possesses such a bond of love with its own body that it never wishes to leave it and will not do so at all unless force is brought to bear on it externally from some very serious disease or trauma.

39. The intellectual and rational nature of the soul, alone possessing mind and word and life-giving spirit, has alone been created more in the image of God than the incorporeal angels. It possesses this indefectibly even though it may not recognize its own dignity nor think or act in a manner worthy of the one who created him in his own image. Therefore, we did not destroy the image even though after our ancestor's transgression through a tree in paradise we underwent the death of the soul which is prior to bodily death, that is, separation of the soul from God, and we rejected the divine likeness. Thus, on the one hand, if the soul rejects attachment to inferior things and cleaves in love to one who is superior by submitting to him through the works and the ways of virtue, it receives from him illumination, adornment and betterment, and it obeys his counsels and exhortations from which it receives true and eternal life. Through this life it receives also immortality for the body joined to it, for at the proper time the body attains to the promised resurrection and participates in eternal glory. But, on the other hand, if it does not reject attachment and submission to inferior things whereby it inflicts shameful dishonour upon the image of God, it becomes alienated and estranged from the true and truly blessed life of God, since if it has first abandoned the one who is superior, it is justly abandoned by him.

40. The triadic nature posterior to the supreme Trinity, since, more so than others, it has been made by it in its image, endowed with mind, word and spirit (namely, the human soul), ought to preserve its proper rank and take its place after God alone and be subject, subordinate and obedient to him alone and look to him alone and adorn itself with perpetual remembrance and contemplation of him and with most fervent and ardent love for him. By these it is marvellously drawn to itself, or rather, it would eventually attract to itself the mysterious and ineffable radiance of that nature. Then, it truly possesses the image and likeness of God, since through this it has been made gracious, wise and divine. Either when the radiance is visibly present or when it approaches unnoticed, the soul learns from this now more and more to love God beyond itself and its neighbour as itself268 and from then on to know and preserve its own dignity and rank and truly to love itself. For he who loves wrongdoing hates his own soul and, in tearing apart and disabling the image of God, he experiences suffering similar to that of madmen who pitilessly cut their own flesh to pieces without feeling it. For he unwittingly inflicts the most miserable sort of harm and rending upon his own innate beauty, and mindlessly breaks apart the triadic and supercosmic world of his own soul which was filled interiorly with love. What could be more wrong, what more ruinous than to refuse to remember, to look upon and to love perpetually the one who created and adorned in his own image and thereby granted the power of knowledge and love and also lavishly endowed those who use this power well with ineffable gifts and with eternal life?

41. One of the creatures inferior to our soul and inferior by far to others is the spiritual serpent and author of evil, who is now become an angel of his own wickedness as a result of his evil counsel to men; he became lower than and inferior to all to the extent that he aspired in his arrogance to become like the Creator in power. By the Creator he was justly abandoned to the same degree that he had previously abandoned him. So great was his defection that he became opposed, contrary and manifestly adversary to him. If then the Creator is living goodness bestowing life on the living, plainly this other one is mortal evil bestowing death. For if the former possesses goodness substantially and is a nature incapable of admitting the contrary, namely, evil, inasmuch as those who have any part in evil whatsoever must not approach him, how much more does he drive as far as possible from himself the creator and originator of evil and its motivation in others? But the evil one possesses not evil but life as his substance and so he lives on immortally in it. However, he possessed life with a capacity also for evil and was honoured with free will in order that by accepting a subordinate status of his own accord and by clinging to the ever-flowing spring of goodness he might have had a share in true life. Since he willingly deserted to evil, he was deprived of true life, justly expelled from that which he had previously fled, and he is become a dead spirit, not in substance (for there is no substance of «deadness») but by rejection of true life. But unsated in his impulse to evil and by his increased state of wretchedness, he made himself into a spirit who confers death in that he eagerly draws man too into fellowship with his own death.

42. As one crooked in his ways and mighty in treacheries, the mediator and agent of death once clothed himself as a crooked serpent in the paradise of God.269 It was not that he himself became a serpent (for that is impossible except in appearance, which at that time he did not know he had to use for fear of possible discovery), but rather, not daring an open encounter, he chose a deceitful one.270 And he chose that whereby he was more confident of escaping notice, in order that by appearing friendly he might secretly introduce most hateful things and by the extraordinary fact of his talking cause stupefaction (for the sensible serpent was not rational, nor did he previously appear able to speak); and in order that he might lure the attentive Eve completely to himself and by his devices easily manipulate her that then he might immediately accustom her to submit to inferior things and become enslaved to those things which it fell to her lot to rule worthily, as she alone among sensible living beings had been favoured by the hand and word of God and made in the image of the Creator.271 But God allowed this in order that man, seeing the counsel coming from that inferior creature (for how much inferior is a serpent to man, and clearly so!), might realize how completely worthless it is and be indignant with his subjection to what is obviously inferior end preserve his proper dignity and at the same time his faithfulness to the Creator by keeping his command. Thus, he will readily become victor over the one who fell from true life; he will justly receive blessed immortality and will abide forever in life divine.

43. No being is superior to man that it should give him counsel or propose an opinion and thereby know and provide what is fitting for him. But this is so only if he guards his own rank, knows himself and the one who alone is superior to him, and if, on the one hand, he gives heed to what he might learn from that one who is superior to him, and if, on the other hand, in what he might learn is not from him, he resolutely accepts God alone as his counsellor. The angels, too, though they surpass us in dignity, yet serve those counsels of his made on our behalf, for «they are ministers sent for the sake of those who are to inherit salvation.»272 This is true not for all the angels, but for those who are good and who preserved their own rank. They possess from God mind, word and spirit, three connatural realities, and they are obliged, as we are, to give their obedience to the Creator, who is mind, word and spirit. They surpass us in many ways, but there are some in which they are inferior to us, namely, as we have said and will say again, with respect to being in the image of the creator, whereby we have come to be more in the image of God than they are.

44. The angels were emphatically ordained to serve the Creator and destined only to be ruled but were not appointed to rule those after them, unless perhaps they should be sent for this purpose by the ruler of the universe. But Satan aspired in his arrogance to rule contrary to the will of the Creator and, when he left his proper rank in the company of his fellow apostate angels, he was justly abandoned by the source or true life and light and he arrayed himself in death and eternal darkness. But since man was appointed not only to be ruled but also to rule all things on earth,273 the archevil one, viewing this with envious eyes, employs every device to depose man from his dominion. While he is unable to do so by force, inasmuch as he is prevented by the Lord of all who created rational nature endowed with both freedom and free will, he treacherously proffers counsel to deprive him of dominion. Thus he robs man, or rather, he persuades him to disregard, treat as nothing and reject, or, rather, to oppose and do the opposite of the command and counsel given by the superior one, and, as man shared in his apostasy, he persuades him to share also in his eternal darkness and death.

45. The great Paul has taught us that the rational soul can exist in such a way that it is dead, though it possesses life as its being; he writes, «The self-indulgent widow is dead even while she lives.»274 He could not have said worse than this about the present subject, namely, the rational soul. For if the soul deprived of the spiritual bridegroom is not sobered, mournful and effectively leading 'the difficult and hard life' of repentance,275 but rather becomes dissipated, abandoned to pleasures and self-indulgent, «it is dead even while it lives» (for in substance it is immortal). It has the capacity for death which is the worse, just as for life which is the better. But even though he speaks of the widow deprived of the corporeal bridegroom, he says she is utterly dead in soul, though self- indulgent and alive in body, since Paul also says elsewhere that «even when we were dead through our trespass, he made us alive together with Christ.»276 And what is it that St. John said: «There is sin which is unto death and there is sin which is not unto death»?277 But even the Lord, who commanded a man to leave the dead to bury the dead, declared those grave diggers to be utterly dead in soul, though alive in body.

46. The ancestors of our race wilfully removed themselves from the remembrance and contemplation of God and by disregarding his command they became of one mind with the deathly spirit of Satan and contrary to the will of the Creator they ate of the forbidden tree.278 Stripped of the luminous and living raiment of the supernal radiance, they too – alas! – became dead in spirit like Satan. Since Satan is not only a deathly spirit but also brings death upon those who draw near to him and since those who shared in his deathliness also possessed a body through which the fell counsel was realized, they communicate those deathly and fell spirits of deathliness to their own bodies. This is the case whenever the human body is dissolved, returning forthwith to the earth from which it was taken,279 unless, conserved by a superior providence and power, it patiently suffers the sentence of the one who bears all things by his word alone, for without his decree nothing at all can be accomplished and it is always carried out justly. For, as the divine psalmist says, «The Lord is just and loves justice.»280

41. According to Scripture, «God did not create death,»281 but rather he prevented its inception insofar as it was necessary and as it was possible in justice to hinder those he had created with free will. For from the beginning he introduced his plan to confer immortality and with a most firm and life-giving counsel he established his commandment. Both the prohibition and the threat were clear: he had stated resolutely that rejection of the living commandment would mean death.282 He did this so that they would preserve themselves from the experience of death either by reason of desire or knowledge or fear.283 For God loves, knows and is able to effect what is good for each one of his creatures. On the one hand, then, if God only knew what was good but did not love it, perhaps he would have stopped and left undone what he knew to be good. On the other hand, if he loved but did not know what was good or was not able to effect it, perhaps, without his willing it, what he desired and knew would remain undone. But since in a special way God loves and knows and is able to effect what is for our good, whatever happens to us through his agency, even without our willing it, happens entirely for our benefit. In whatever we willingly involve ourselves by our natural endowment with free will, great is the fear that it should turn out to be for our misfortune. Whenever in God's providence some one thing among all others is emphatically forbidden -as, for example, in paradise and in the Gospel by the Lord himself, among the offspring of Israel through the prophets, in the law of grace through his apostles and their successors – it is clearly most unprofitable and destructive to desire that thing for itself and eagerly seek after it. And if someone proffers it to us and urges us to seek it eagerly, using persuasive words and luring us with attractive forms, he is clearly inimical and hostile to our lives.

48. Therefore, either out of desire, since God desires us to live (for why would he have created us living unless he particularly wanted it so?), or because we recognize that he knows what is good for us better than we do (for how could the one who granted us knowledge not be the Lord of knowledge284 to an incomparably greater extent?), or out of fear for his all-powerful might, we ought not to have been misled, lured and persuaded at that time into rejecting God's command and counsel. And the same is true now for the saving commandments and counsels given to us after the first one. Just as now those who high-mindedly refuse to stand opposed to sin and who set at nought the divine commandments attain the contrary, namely, that which leads to interior and eternal death, unless they regain their souls by repentance, so in the same way our two ancestors, by not opposing those who persuaded them to disobey, disregarded the commandment. Because of this the sentence announced to them beforehand by the one who judges justly immediately went into effect and accordingly as soon as they ate of the tree they died. Then they understood in reality what was the commandment of truth, love, wisdom and power given to them and which they had forgotten. In shame they hid themselves,285 stripped of the glory which grants a more excellent life to the immortal spirits and without which the life of the spirits is believed to be and is indeed far worse than many deaths.

49. That it was not yet to our ancestors' benefit to eat of that tree is shown by the quotation: «The tree, in my opinion, represented contemplation, which can be safely approached only by those with a more perfect disposition, but it is not good for those who are still quite immature and greedy in their desires, just as 'perfect food is of no use for those still immature and requiring milk'.»286 But even if you do not want to transfer the significance of that tree and its fruit anagogically to contemplation, it is not very hard, I think, to see that it was not yet of benefit to those who were still imperfect. In my opinion, as far as the senses were concerned, among the trees in paradise that one was the most pleasant to look upon and to eat from. But the food most pleasant to the senses is not truly and necessarily good, nor always good, nor good for everyone. Rather it is good for those who are able to enjoy it in such a way that they are not overcome and who do so when it is necessary, to the extent that it is necessary and for the glory of the one who has created it. But it is not for those unable to enjoy it in this way. For this reason I think that tree was called ‘the tree of the knowledge of good and evil.’287 For it belongs to those with a perfect disposition of divine contemplation and virtue to be familiar with the most pleasant of sensible things without also drawing their mind away from contemplation of God and from hymns and prayers addressed to him. It also belongs to these to make the most pleasant of sensible things the material and the starting point for the ascent to God and to overcome sensible pleasure completely through the movement of the intellect towards superior things, even though such a movement may be strange, considerable and quite violent, still more because of its strangeness, namely, the effort not to deprive the soul of its rationality for the sake of what at that time is evil yet thought to be good by one who is captured by it and overcome utterly.

50. Therefore, while they lived in that sacred land, it was to the profit of our ancestors and it was incumbent upon them never to have forgotten God, to have become still more practised and, as it were, schooled in the simple, true realities of goodness and to have become accomplished in the habit of contemplation. But experience of things pleasant to the senses is of no profit to those who are still imperfect, those who are in mid-course and who, compared with the strength of the experienced, are easily displaced towards good or its opposite. And the same applies to those who by nature greatly degrade these things and who dominate and draw down the entire mind in company with the senses and give way to the evil passions and prove the persuasiveness of the originator and creator of such passions of which the origin, after Satan, was the impassioned eating of the sweetest victuals. For if sight alone of that tree, according to the account, rendered the serpent an acceptable and trustworthy counsellor, how much more would the sense of taste do so for subsequent generations? And if this is true for taste, how much more for eating to satiety? Is it not clear that it was not yet to the advantage of our ancestors to eat of that tree by way of the senses? Because they did not eat from it at the proper time, was it not needful that they be expelled from the paradise of God288 lest they make that divine land into a counsel chamber and workshop of wickedness? Would it not have been fitting if the transgressors had experienced death also of the body immediately at that time? But the master was forbearing.

51. The sentence of death for the soul which the transgression put into effect for us was according to the Creator's justice, tor without compulsion he abandoned those who abandoned him when they became self-willed. That sentence had been announced by God beforehand out of his love for man,289 for the reasons we have mentioned. But he restrained and deferred at first the sentence of bodily death and when he pronounced the sentence, out of the depth of his wisdom and the abundance of his love for man he postponed its execution for a future time: he did not say to Adam, 'Return from whence you were taken!,' but rather, «You are earth and unto earth you shall return.»290 Those who listen intelligently can see from these words that God did not make death, neither for the soul nor for the body.291 For neither did he at the first give the command saying, 'Die on the day that you eat of it!’ but rather, «You shall die on the day you eat of it.»292 Nor thereafter did he say, 'Return now unto the earth!,' but rather, «You shall return.»293 After the prior announcement he let the matter go, but without hindering its just outcome.

52. Death, then, was to follow our ancestors just as it is laid up even for those who outlive us, and our body was rendered mortal. There is also a lengthy process which in a manner of speaking is a death, or rather, ten thousand deaths following one after the other in succession, until we should come to the one final and long-lasting death. For we come into being in corruption and while coming to be we are passing away until we cease both passing away and coming to be. We are never truly the same even though to the inattentive we may seem to be. Just as with the flame of a thin reed held at the end – for that too changes from one moment to the next – the length of the reed is the measure of its existence, similarly with us too in our transience the span of life given to each man is the measure of his existence.

53. Lest we be entirely unaware of the abundance of his love for man and the depth of his wisdom, God deferred the execution of death on this account and granted man to live for a long time still. In the beginning he showed compassion in his discipline, or rather, he permitted a just discipline lest we despair completely. He also granted a time for repentance and a new life pleasing to him. He alleviated the sorrow of death by a succession of generations. He increased the race with successors so that the multitude of those begotten would initially exceed by a large measure the number of those who died. In place of the one Adam, who became pitiable and poor because of the sensible beauty of the tree, God displayed many who proceeded from sensible things to become blessedly rich in knowledge of God, in virtue, in knowledge and in divine favour: witness Seth, Enosh, Enoch, Noah, Melchisedek, Abraham, and those who have appeared between, before and after them, who were like them or nearly so. But since among so many no one lived entirely without sin so as to be able to revoke that defeat of our ancestors and to heal the wound at the root of our race and to suffice for the sanctification, blessing and return of life for all who followed, God provided for this and made a choice from the nations and tribes whence there would arise the celebrated staff from which would come the flower294 whereby he would accomplish the saving economy of the entire race.

54. ‘O the depth of God’s riches, wisdom and love for mankind!’295 For if there had been no death, and if prior to death our race had not been mortal because of such a root, we would not in fact have gained the riches of the first fruits of immortality, nor would we have been summoned up to heaven, nor would our nature have been enthroned above every principality and power ‘at the right hand of the Majesty in the heavens,’296 Thus, by his wisdom and power and out of love for mankind God knows how to change to the better the falls which result from our freely willed deviation from the course.

55. Many people perhaps blame Adam for the way he was easily persuaded by the evil counsellor and rejected the divine commandment and through such a rejection procured our death. But it is not the same thing to want a taste of some deadly plant prior to testing it and to desire to eat of it after learning by the test that it is deadly. For a man who takes in some poison after testing it and wretchedly brings death upon himself is more culpable than the one who does this and suffers the consequences prior to the test. Therefore, each of us is more abundantly culpable and guilty than Adam. But is that tree not within us? Do we not, even now, have a commandment, from God forbidding us to taste of it? This tree is not found in us in the same way as the former one, but the commandment of God is with us even now. On the one hand, if we obey it and set our will to live by it, it frees us from the punishment for all our sins and from the ancestral curse and condemnation. But, on the other hand, if we reject it even now and prefer to it the temptation and counsel of the evil one, we cannot but be banished from that life and society in paradise and fall into the Gehenna of eternal fire with which we were threatened.

56. What then is this commandment now laid before us by God? It is repentance, of which the principal characteristic is to touch forbidden things no more. For we were cast out of the land of divine delight and justly shut out from the paradise of God, and we have fallen into this pit and have been condemned to dwell and live out our lives in the company of the irrational animals and have rendered beyond hope the advent of our recall to paradise. Because of this, God, who at that time rendered his judgement in justice, or rather, allowed this to come upon us justly, now out of his goodness and love for mankind, for the sake of his mercy and compassion,297 has come down to us for our sake. According to his good pleasure he became a man like us except for sin that he may teach us anew and rescue like by like, and he introduced the saving counsel and commandment of repentance, saying to us, «Repent for the kingdom of heaven is at hand.»298 Prior to the incarnation of the Word of God the kingdom of heaven was as far from us as the sky is from the earth. But when the King of heaven sojourned among us and was pleased to become one with us, the kingdom of heaven drew near to us all.

57. Now that the kingdom of heaven has drawn near to us through the condescension of God the Word unto us, let us not remove ourselves far from it by living an unrepentant life. Rather, let us flee the wretchedness of «those who sit in darkness and the shadow of death.»299 Let us acquire the works of repentance: a humble attitude, compunction and spiritual mourning, a gentle heart full of mercy, loving justice, striving for purity, peaceful, peacemaking, patient, glad to suffer persecutions, losses, disasters, slander and sufferings for the sake of truth and righteousness. For the kingdom of heaven, or rather, the King of heaven – O the unspeakable munificence! – is within us.300 To him we ought always to cling by works of repentance and perseverance, loving as much as possible him who loved us so much.

58. The absence of passions and the presence of virtues establish love of God, for hatred of evil things and the consequent absence of the passions introduce instead the desire for and the acquisition of good things. How could one who loves and possesses good things not love in a special way the master who is goodness itself and who alone is both provider and preserver of all good? In him he has his being in a singular manner and him he bears within himself through love, according to the one who said, «He who abides in love abides in God and God in him.»301 You should know not only that love for God is based on the virtues, but also that the virtues are born of love. And so the Lord says at one point in the Gospel, «He who has my commandments and keeps them, he it is who loves me»;302 and on another occasion, «He who loves me will keep my commandments.»303 But neither are the works of virtue praiseworthy and profitable for those who practise them without love, nor indeed is love without works. Paul at one time makes ample demonstration of this when he writes to the Corinthians, «If I do such and such but have not love, I gain nothing.»304 And in turn, at another time, the disciple specially beloved by Christ does likewise when he says, «Let us not love in word or speech but in deed and in truth.»305

59. The supreme and worshipful Father is Father of Truth itself, namely, the Only-Begotten Son. And the Holy Spirit has a spirit or truth, just as the Word of Truth demonstrated previously. Therefore, those who worship the Father in spirit and truth and hold to this manner of belief also receive the energies through these. ‘For the Spirit,’ says the Apostle, ‘is the one through whom we offer worship and through whom we pray’;306 and the Only-Begotten of God says, «No one comes to the Father except through me.»307 Therefore, 'those who thus worship the supreme Father in spirit and truth are the true worshippers.'308

60. «God is spirit and those who worship him must worship in spirit and truth,»309 that is, by conceiving the incorporeal incorporeally. For thus will they truly see him everywhere in his spirit and truth. Since God is spirit, he is incorporeal, but the incorporeal is not situated in place, nor circumscribed by spatial boundaries. Therefore, if someone says that God must be worshipped in some definite place among those in all earth and heaven, he does not speak truly nor does he worship truly. As incorporeal, God is nowhere; as God, he is everywhere. For if there is a mountain, place or creature where God is not, he will be found circumscribed in something. He is everywhere then, for he is boundless. How then can he be everywhere? Because he is encompassed not by a part but by the whole? Certainly not, for once again in that case he will be a body! Therefore, because he sustains and encompasses the universe, he is in himself both everywhere and also beyond the universe, worshipped by true worshippers in his spirit and truth.310

61. The angel and the soul, as incorporeal beings, are not located in place but neither are they everywhere, for they do not sustain the universe but rather are dependent upon the one who sustains them. Therefore, they belong in the one who sustains and encompasses the universe in that they are appropriately bounded by him. The soul therefore as it sustains the body together with which it was created is everywhere in the body, not as in a place, nor as if it were encompassed, but as sustaining, encompassing and giving life to it because it possesses this too in the image of God.

62. Not in this respect alone has man been created in the image of God more so than the angels, namely, in that he possesses within himself both a sustaining and life-giving power, but also as regards dominion. Contained in the nature of our soul there is on the one hand a faculty of governance and dominion and on the other hand one of natural servitude and obedience. Will, appetite, sense perception and generally those things subsequent to the mind were created by God together with the mind, even though we are sometimes disposed towards sin in our will and rebel not only against our God and universal sovereign but also against the ruling power belonging to us by nature. Nevertheless, because of the faculty of dominion within us God gave us lordship over all the earth.311 But angels do not have a body joined to them so that it is subject to the mind. The fallen angels have acquired an intellectual will which is perpetually evil, while the good angels have acquired one that is perpetually good and required no charioteer at all. The evil one did not own, rather he stole power over the earth, whence it is clear that he was not created as ruler of the earth. The good angels were appointed by the universal sovereign to keep watch over the affairs of earth after our fall and the reduction of our rank that ensued, even though it was not complete because of God's love for mankind. As Moses says in the Ode, 'God established bounds for the angels when he divided up the nations.'312 This division had taken place after Cain and Seth, with the posterity of Cain being called men while the descendants of Seth were called sons of God. As it seems to me, the name thereafter distinguishes and foretells the race from which the only-begotten Son of God would take flesh.

63. In company with many others you might say that also the threefold character of our knowledge shows us to be more in the image of God than the angels, not only because it is threefold but also because it encompasses every form of knowledge. For we alone of all creatures possess also a faculty of sense perception in addition to those of intellection and reason. This faculty is naturally joined to that of reason and has discovered a varied multitude of arts, sciences and forms of knowledge: farming and building, bringing forth from nothing, though not from absolute non-being (for this belongs to God), he gave to man alone. Scarcely anything at all effected by God comes into being and falls into corruption but rather, when one thing is mixed with another among the things in our sphere, it takes another form. Furthermore, God granted to men alone that not only could the invisible word of the mind be subject to the sense of hearing when joined to the air, but also that it could be put down in writing and seen with and through the body. Thereby God leads us to a clear faith in the visitation and manifestation of the supreme Word through the flesh in which the angels have no part at all.

64. But even though we possess the image of God to a greater degree than the angels, even till the present we are inferior by far with respect to God's likeness and especially now in relation to the good angels. Leaving other things aside for now, the perfection of the likeness of God is effected by the divine illumination that comes from God. I should think that no one who reads the divinely inspired scriptures carefully and intelligently would be unaware that the evil angels have been deprived of this illumination and therefore are under darkness, whereas the divine minds are informed thereby and so are called «a secondary light and an emanation of the First Light.»313 Thence the good angels possess also knowledge of sensible things, for they apprehend these things not by a sensible and natural power but rather know them by means of a divine power, from which nothing present, past or future can be hidden.

65. Those who participate in this illumination, possessing this to a certain degree, possess also the knowledge of beings to a proportionate degree. All who have read the divinely wise theologians with some care know that the angels too have a share in this illumination, that it is uncreated and that it is not identical with the divine substance. But those who hold the opinions of Barlaam and Akindynos blaspheme against this divine illumination, since they maintain either that it is a creature or that it is the substance of God, and when they call it a creature they do not allow this to be a light belonging to the angels. So let the divine revealer of the Areopagus now come forward to clarify briefly these three matters, for he says, «As the divine minds move in a circle they are united with the illuminations of the good and the beautiful which are without beginning and without end.»314 It is clear to everyone, then, that he is calling the good angels divine minds, and by presenting these illuminations in the plural he has distinguished them from the substance of God for that is one and altogether indivisible. And when he adds «without beginning and without end» to his statement, what else has he indicated to us but that the illuminations are uncreated?315

66. Now that our nature has been stripped of this divine illumination and radiance as a result of the transgression, the Word of God has taken pity on our disgrace and in his compassion has assumed our nature and has manifested it again to his chosen disciples, clothed more remarkably on Tabor.316 He indicated what we once were and what we shall become through him in the future age if we choose here below to live according to his ways as much as possible, as John Chrysostom says.317

67. Before the transgression Adam too participated in this divine illumination and radiance, and as he was truly clothed in a garment of glory he was not naked, nor was he indecent because he was naked. But he was far more richly adorned, it is not too much to say, than those who now wear diadems ornamented with much gold and shining stones. The great Paul calls this divine illumination and grace our heavenly dwelling place when he says, «Here we groan and long to put on our heavenly dwelling, so that by putting it on we may not be found naked.»318 On his way from Jerusalem to Damascus Paul too received from God the pledge of this divine illumination and of our investiture – to use the words of the Gregory who has been aptly named after Theology – «before he was cleansed of his persecuting, when he conversed with the one he was persecuting, or rather, with a brief flash of the great Light.»319

68. The divine transcendent being is never named in the plural. But the divine and uncreated grace and energy of God is divided indivisibly according to the image of the sun's ray320 which gives warmth, light, life and increase, and sends its own radiance to those who are illuminated and manifests itself to the eyes of those who see. In this way, in the manner of an obscure image, the divine energy of God is called not only one but also many by the theologians. For example, Basil the Great says, «As for the energies of the Spirit, what are they? Ineffable in their grandeur, they are innumerable in their multitude. How are we to conceive what is beyond the ages? What were his energies before intelligible creation?»321 Prior to intelligible creation and beyond the ages (for also the ages are intelligible creations) no one has ever spoken or conceived of anything created. Therefore, the powers and energies of the divine Spirit are uncreated and because theology speaks of them in the plural they are indivisibly distinct from the one and altogether indivisible substance of the Spirit.