5. Icon themes

28. Mandylion, Russia, 1st half 19th century, 53.8 · 44.3 cm, Zoetmulder icon collection

Christ

Theologically, the icon of Christ is the most important icon of all. When Christ became a man, he became visible and thus also capable of being represented.

But how should Christ be represented? The earliest pictures of Christ show him as a young man without a beard. In a fresco dating from the 4th century, in the catacomb of Peter and Marcellinus in Rome, however, Christ is pictured with shoulder-length hair and a short beard, very much like what later became the prototypical image seen in the Christ icon.

From the earliest Christian period, the faithful felt it was important to know which the true and authentic image of Christ was. Much was written about the subject and many legends arose. Unlike the idols of heathens, which were made by human hand, the earliest image of Christ was believed to have been created miraculously. Christ himself, it was said, left the image of his face on a linen cloth. In 944, this cloth was sold for a great sum of money to the Emir of Edessa and taken to Constantinople. There it was called Mandylion, from the Arabic word mandyl (‘cloth’). It is said to be captured by the Crusaders during the sack of the city in 1204, when it was taken to the West. [28]

The oldest preserved representation of a Mandylion can be found in the upper part of a triptych from the 10th century in the Monastery of St Catherine in the Sinai. This shows King Abgar receiving the Mandylion. The main difference between the way Christ is represented in the West and the way he is portrayed in East is that the Western Mandylion (the veil of St Veronica), relates to the suffering of Christ, who is therefore shown wearing a crown of thorns; whereas the Mandylion from the East (the cloth of King Abgar) relates to the ‘representability’ of Christ. God is made visible through Christ. A Mandylion icon shows only the face of Christ, without neck and shoulders. Sometimes the panel itself is seen as the cloth; sometimes a cloth is shown with the face of Christ on it; and sometimes this cloth is held by angels. Christ is shown with a dark beard and his hair parted in the middle. The eyebrows are strongly accentuated. The closest to this type of Mandylion icon is the portrait popularly referred to as ‘The Fiery Eye’ (Yaru Oko in Russian). In it, Christ’s face, neck and upper shoulders fill the whole panel. [29]

29. Christ, Russia (Moscow), 17th century, 51 · 41.5 cm, Ikonen-Museum Recklinghausen

30. Christus Pantocrator, Cyprus, 16th century, 33 · 26.7 cm, private collection (Russia)

31. Christ in Majesty with the Heavenly Powers, Russia (Moscow), 2nd half 17th century, 79 · 63 cm, IkonenMuseum Recklinghausen

The icon image of Christ found most frequently is Christ Pantocrator. The oldest example of this goes back to the 4th century. The Greek word pantokrator means ‘ruler of all’ (Gospod Vsederzitel in Russian). In this type of icon, Christ is depicted as a Byzantine emperor. He is holding up his right hand, often with his index and middle finger together in the sign of the blessing, sometimes crossed to indicate his dual nature, divine and human. In his left hand, he holds a Gospel book, which may be open or closed. If the book is open, Christ is often showing the viewer either a text from Matthew 11:28: ‘Come to me, all you who are weary and burdened, and I will give you rest’, or else from John 14:6: ‘I am the Way, the Truth and the Life.’ Christ is clothed in a purple-red tunic, the colour purple referring to his divine nature. Over this he wears a blue cloak, the colour blue indicating the human nature that Christ took on when he came to earth. Christ has a halo around his head. This usage stems from the Greek and Roman period, when gods and goddesses who appeared on earth were depicted with a halo to indicate their supernatural origin (reflecting the fact that they lived in the heavens with the sun and the stars). Like them, Christ is illuminated by the heavenly and eternal light. Christ’s halo contains the sign of the cross [30], bearing the Greek inscriptions IC XC (‘Jesus Christ’) and O ΩN (‘the Being’ or ‘He who is’), based on ‘I am that I am’ from Exodus 3:13–14. These inscriptions are also found on Russian icons. [29]

Besides this highly popular type of icon, there are also icons in which Christ is pictured sitting on a throne [31] or shown full-length, with several saints kneeling at his feet. In addition, some icons show symbolic portraits of Christ, such as The Wisdom of God, The Unsleeping Eye [32] and The Blessed Silence.

In fact, every icon, whatever its subject matter, contains some reference to Christ, whether it is a hand visible at the edge of cloud, a cross held by a saint, or a scroll carried by a prophet.

32. Christ ‘Unsleeping Eye’, Russia, mid-16th century, with silver-gilt basma, 31.7 · 26.2 cm, IkonenMuseum Recklinghausen

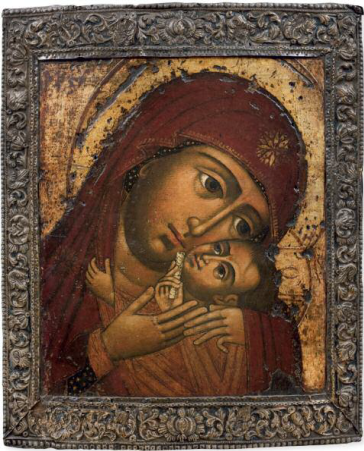

The Mother of God

The Mother of God is shown on icons as often – or even more often – than Christ himself. In a sense, the Mother of God icon takes precedence over all other icons, because without the Mother of God there would have been no image of Christ.

The first icon of the Mother of God was not an icon ‘not made by human hands’, but was believed to have been painted by St Luke, the Evangelist. This origin guarantees the icon’s authenticity. An icon, after all, cannot simply be invented. This explains the many legends about Mother of God icons. Some were said to have fallen from Heaven or to have been cast up from a river, while others were believed to have been dug up. The painter had to copy these icons, and the more replicas of the original icon there were, the more powerful the icon became.

Every Mother of God icon has certain fixed elements. For example, the Mother of God always wears a blue tunic to indicate her human nature. Over it, she wears a purple cloak as a sign that she has received the grace of God. Stars are shown on her veil. These three stars are subject to different interpretations: they are said to refer to the Trinity, to symbolise her virginity (before, during and after Christ’s birth), or to stem from an old Syrian custom of embroidering three stars on the bridal veil of princesses as a symbol of purity. Every Mother of God icon also bears the Greek letters MR QU, the abbreviation of ‘Mother of God’ in Greek (Mèter Theou).

There are as many as 800 different Mother of God icons, and each has its own name. Many of these names refer to the icon’s place of origin or to the church or other place where it is venerated. Well-known examples are the Mothers of God of Vladimir [36], Tichvin, Kazan [34], Korsun, Shuya, Tolga, Volokolamsk and Smolensk (to mention just a few).

33. Mother of God Hodegitria, Crete, c.1500, 50.9 · 39 cm, Ikonen-Museum Recklinghausen

34. Mother of God of Kazan, Russia, 2nd half 17th century, 31 · 26.5 cm, Zoetmulder icon collection

Mother of God icons can be divided into four main types. The oldest type is the Hodegitria, Greek for ‘She who shows the Way’. This is the icon that was believed to have been painted by St Luke, and to have been taken from Jerusalem to Constantinople in the 5th century. Its name comes from the fact that Mary is shown gesturing towards ‘Him who calls himself the Way’. Both she and the Christ Child are looking straight ahead. The Hodegitria is usually a very dignified icon. The Mother of God has something regal about her, and does not seem to be showing affection to her son. In the portrayal of Christ, his divine nature is emphasised: he seems to be conscious of his special task, and is wise beyond his years. He is sitting on his mother’s left arm, with his right hand raised and his left hand holding a closed scroll. Russians refer to this type as the Hodegitria of Smolensk, because it was brought to Russia in 988 by the Byzantine Princess Anna when she married Vladimir of Kiev, and later ended up at Smolensk in 1101. [35]

The Eleousa (‘Mother of God of Tenderness’) is quite different. It shows Mary and Jesus cheek to cheek. Mary seems filled with sadness, as if she is already mindful of her son’s future suffering. They appear to be comforting each other in a loving embrace. This type arose in the 12th century, when Byzantine art started to pay more attention to the expression of human feeling. The best-known icon of this type is the Mother of God of Vladimir (Vladimirskaya). [36] This icon was taken to Kiev in the early 12th century as a gift from the Byzantine imperial court, and was later taken to the city of Vladimir, from where it derives its name. In 1395, the Vladimirskaya was taken to Moscow, when Vladimir was threatened by the Turkic armies of Timur. After the Turkic troops had been driven back – thanks to the Vladimirskaya – the icon was placed in a church in the Kremlin. From here, it was repeatedly brought out to help the Russian armies achieve their victories over the Mongols. The icon was given the honorific title of ‘Mother of Russia’, and it now hangs in the Tretyakov Museum in Moscow. A few other well-known Eleousa icons are the Mother of God of Korsun (Korsunskaya) [37] and the Mother of God of Feodorov (Feodorovskaya).

The third type is the Mother of God Enthroned. One of the oldest known icons of this type is from the 6th century and is found at the Monastery of St Catherine in the Sinai. [40] The icon has a solemn, formal appearance. The Mother of God looks straight ahead and has the child in her lap. The image is analogous to ancient Egyptian, Greek and Roman representations of mothers of god (e.g., the image of the Egyptian goddess Isis with her son Horus). The most frequently occur ring icon of this type in Russia is the Mother of God of the Cave Monastery in Kiev (Pecherskaya). On either side of the Mother of God stand the two founders of the Cave Monastery, Antony and Feodosy. [39]

35. Mother of God Hodegitria of Smolensk, Russia, 17th century, 34.5 · 28 cm, Ikonenmuseum Kampen

36. Mother of God of Vladimir (Vladimirskaya), 16th century, 28.5 · 23.5 cm, private collection (USA)

37. Mother of God of Kasperow (Kasperovskaya), Russia, early 18th century, with metal basma, 32 · 27 cm, Ikonen-Museum Recklinghausen

38. Pokrof of the Mother of God, Russia, late 16th century, 97.5 · 69.5 cm, Ikonenmuseum Kampen

39. Mother of God Pecherskaya, Russia, 18th century, 56 · 40.5 cm, Ikonenmuseum Kampen

The fourth type is the Praying Mother of God. The Mother of God is pictured in the ancient praying attitude, with the hands raised up and spread. On her chest she wears a round shield with a picture of Christ Emmanuel, Christ as child. This representation of the Mother of God was believed to have arisen in the 4th or 5th century, but appears for the first time in the 9th century in the Blacherne Church in Constantinople. This icon, known as the Blachernitissa, became a symbol of the city. It was destroyed in a fire in 1434. In Russia, this Mother of God icon is called Znamenny (‘of the sign’), based on Isaiah 7:14: ‘The Lord himself shall give you a sign’. The Znamenny was considered the guardian icon of the city of Novgorod, because with its help an attack by the Grand Duke Andrey Bogolubsky was repulsed in 1170. [41]

The above are the most significant icon types, but many others were also developed, inspired by miracles, human needs, hymns and liturgical texts. [38, 42]

40. Mother of God Enthroned, 6th century, 68.5 · 49.7 cm, St Catherine’s Monastery, Sinai

41. Mother of God of the Sign of Novgorod, 2nd half 17th century, traces of metal basma, 34 · 29.7 cm, Ikonen-Museum Recklinghausen

42. Nursing Mother of God, Russia, early 18th century, 32 · 27.5 cm, Ikonen-Museum Recklinghausen; detail p. 62

Church feasts

In addition to icons showing Christ and the Mother of God, there are also icon types that celebrate the major events in the lives of both of them. These are the church feasts. Painters took their inspiration from the Bible, the apocryphal writings, the Orthodox liturgy and the sermons of the Church Fathers. There are twelve main feasts, known as the Dodekaorton. Thefeast icons are displayed on the third row of the iconostasis.

The linear order in which the icons are hung follows the chronology of the events or the calendar of the Orthodox Church, which runs from 1 September to 31 August. The icon of the Resurrection is also usually added to this row. In addition to the icons on the iconostasis, an icon of the feast was placed on a stand in the church during the celebration of the feast.

The first feast in the year is the Birth of the Mother of God (8 September). It was already being celebrated in the 7th century. The representation of this event is based on the apocryphal Proto-Gospel of James, which dates from the 2nd century. This tells of the sadness of the childless pair, Joachim and Anna. Encouraged by an angel, they meet at the Golden Gate in Jerusalem and embrace. [43] Anna gives birth to a daughter, Mary. The icons representing the birth of Mary are domestic and intimate in tone. Anna lies on her childbed and servants bring her sustenance. The midwife prepares the bath for the newborn child. To the right, the parents sit close together, holding the baby Mary on their lap. [44]

The second feast, the Entry of Mary in the Temple (21 November), is also based on the Proto-Gospel of James. Mary’s parents dedicate the child to God, taking her to the temple when she is three. She spends the rest of her youth there, fed by angels.

The feast of the Annunciation (25 March) celebrates the occasion when, nine months before Christmas, the Archangel Gabriel tells Mary that she will give birth to the Son of God. Based on the Gospel of Luke, this event has inspired many artists in both Eastern and Western traditions. The first representation of it is found in a fresco dating from the 2nd century in the catacombs of Priscilla in Rome. Besides appearing in the row of feasts on the iconostasis, the Annunciation is also shown on a pillar or wall of the church and in the upper part of the Royal Doors. The icon shows the Archangel Gabriel standing opposite Mary, bringing her the message. Depending on the opinion and inspiration of the artist, Mary’s reaction ranges from surprise to calm acceptance. [45] Sometimes, the Angel Gabriel is shown twice. The famous Byzantine Akathist Hymn speaks of Gabriel standing still ‘in awe’ before delivering the message.

The feast of the Nativity is celebrated on 25 December. The iconography is based on the Gospels, the Proto-Gospel of James and the Orthodox liturgy. The earliest known representation is a fresco from the 4th century in the catacombs of St Sebastian in Rome. In the Birth of Christ icon, within a rugged mountain landscape, the Mother of God lies resting, turned away from the child. The child lies behind her, before the entrance of a cave, where a donkey and ox keep him warm. The colour of the bed on which Mary is lying is purple-red, the imperial colour. On the left, the three Wise Men are shown arriving from the East. They have followed the Star of Bethlehem, which appears above in the centre. Their Phrygian caps indicate that they have come from a foreign country. Their quest is at an end and they come bearing gifts. To the right, behind the mountains, an angel bends down to a shepherd, who is looking up, rather surprised. To the left, two angels are singing praise.

Below to the right we see the Christ Child’s first bath. The bath scene is taken to be a reference to Christ’s human nature. Christ is sitting on the lap of Salome, the bare-armed midwife. When Salome hears about Mary’s virginity, she is sceptical, and when she later touches Mary, her hand shrivels. But she is healed again by touching Christ. A maidservant is filling the bath with water. To the left, Joseph, dressed in a green robe, is sitting on a rock in a dark cave. He is bent forward in thought, and seems to play no part in the events taking place so close to him. What is he thinking about? A grey-haired man is bending down towards him. Who is he? Some see in him the personification of doubt: perhaps Joseph is having doubts about his wife’s virginity. Others see in this figure the prophet Isaiah, looking like an eastern hermit, who has come to explain his prophecy: ‘Behold, a virgin will be with child and bear a son, and she will call his name Emmanuel’ (Isaiah 7:14).

43. The Meeting of Anna and Joachim, Russia, late 16th century, 32 · 27 cm, Ikonen-Museum Recklinghausen

44. Birth of the Mother of God, Russia, 19th century, 35 · 31 cm, private collection (Belgium)

45. The Annunciation to Mary, Russia (Novgorod), late 15th century, 56.5 · 43 cm, Ikonen-Museum Recklinghausen

46. The Nativity, 16th century, 31 · 26.5 cm, Collection of Jan Morsink (Amsterdam)

47. St Simeon the God-Bearer, Russia, 19th century, 31 · 26.5 cm, private collection (The Netherlands)

48. The Presentation of Christ in the Temple, Russia (Novgorod), late 15th century, 47.8 · 36.2 cm, IkonenMuseum Recklinghausen

49. The Baptism of Christ, Russia, 16th century, 31 · 26.5 cm, private collection (The Netherlands)

The Christmas icon is rich in symbolism, elucidating the meaning of Christ’s birth. The black depths of the cave symbolise the darkness surrounding humanity. The child, wrapped in white swaddling clothes, is the divine light. The dark cave, the white swaddling clothes and the coffin are symbols of death. Already from his birth, everything indicates symbolically that Christ has come to conquer death and darkness through his own death. [46]

The feast of the Presentation of Christ (2 February) is normally called Candlemas in the Western tradition, because candles used during the Church year are blessed on that day. The oldest representation of this feast dates from the 5th century, and can be seen on the triumphal arch at the Santa Maria Maggiore Church in Rome. The representation in the icon follows faithfully the account given in Luke 2:22–38. To the right, on a platform by the altar, stands Simeon, an old man from Jerusalem. He bends deeply over the child, which he holds lovingly in his hands. [47] Opposite him stand the Mother of God and Joseph. [48]

The Baptism of Christ (6 January) marks the baptism of Christ by St John the Baptist. Early representations of this event are found in the catacombs, but the 5th-century mosaic in the Arian Baptistry in Ravenna is decisive for the iconography. The Baptism of Christ is the first revelation of the Holy Trinity: the Father speaks, the Spirit descends to Christ, and Christ allows himself to be baptised as the Son of Man. On a Russian icon from the 16th century, Jesus stands naked in the Jordan. His posture – arms bent lightly by his side – indicates surrender. He is facing John. John, in his characteristic clothing, bends deeply before him, and puts his right hand on Christ’s head. Water is traditionally seen as an element of darkness: Christ breaks through this realm of darkness. On the other side of the river stand three angels. The hands of the two foremost angels are covered by white cloths. They bend forward reverently and attentively to witness the special event. The third angel, by contrast, is rising, looking up at the heavens. Can he hear the voice of God? Does he see the heavens open? The Holy Spirit comes down from Heaven in the form of a dove. At the very top, a dark blue semicircle symbolises God the Father. A blue ray of light shines from that circle, dividing into three. [49]

The Transfiguration (6 August) celebrates the exaltation of Christ on Mount Tabor. The oldest representation dates from the 6th century, and is found in the apse of the main church of the Monastery of St Catherine in the Sinai. The representation of the Transfiguration plays an important part in Orthodox theology and mysticism. The Mount Tabor icon was thought to be the most difficult to make: every apprentice icon painter in Russia had to make one as his ‘masterpiece’. If he could produce a convincing Transfiguration icon, he was admitted to the Guild as a master of his craft.

In an almost surrealistic mountain landscape, Christ stands in shining white clothes, surrounded by a Mandorla. His feet are not touching the ground, nor are those of Elijah and Moses, who appear beside him. In the foreground, the Apostles Peter, John and James are lying flat on the ground in amazement. St Peter, shown to the left, is beginning to get up. James thoughtfully bows his head. John, in the middle, seems to have sunk into a deep meditation. [50]

The Entry into Jerusalem is celebrated on the Sunday before Easter. The feast is also known as Palm Sunday. As reported by the traveller and pilgrim Egeria4, processions in which people carried palm branches were already being held in the 4th century. The iconography of the representation is based on John 12:12–15, Mark 11:1–11 and Luke 19:28–40: Christ riding on a donkey enters Jerusalem through the city gate withhis disciples, and is greeted by the Jews. Since donkeys were unknown in Russia, Christ is usually depicted riding a white horse.

The icon of the Crucifixion of Christ does not actually belong in the Dodekaorton. The oldest representation of the Crucifixion is a miniature from the Syrian Codex of Rabula, a manuscript dating from 586. Although the cross is the Christian symbol par excellence, representations of the crucified Christ were not popular. In the Russian tradition, the cross has three horizontal beams, the lowest of which slants upwards (on Christ’s right). The slanting crossbeam is generally interpreted as a balance. At the foot of the cross we see the witnesses of the Crucifixion: on the left, we see Mary, Mark and Mary Magdalene; and on the right we see John, Jesus’ favourite disciple, with the Roman centurion Longinus. [51]

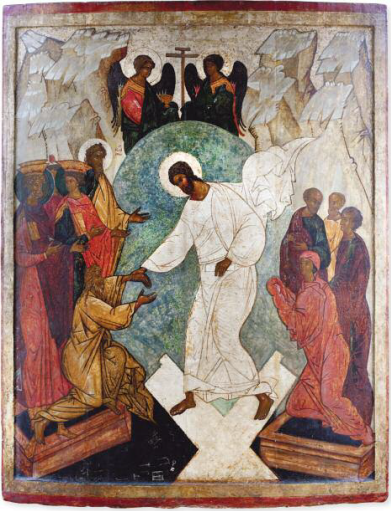

The highpoint of the year in the Eastern Church is Easter and not, as in the West, Christmas. In Russia, Easter comes just as nature is being reborn after the long, hard Russian winter. On Easter Day, the faithful greet each other with the words the Apostles uttered when they heard about Jesus’ Resurrection: ‘Christ has risen; He has risen indeed’.

One Easter custom is the giving of coloured eggs: magnificently painted eggs, sometimes decorated with precious stones, survive from the Tsarist period. The idea behind this custom is that, just as life is initially hidden within the eggshell and then emerges, so Christ has risen from the grave: his Resurrection symbolises victory over death. The Resurrection of Christ is not actually described in the Bible: there is only an indirect reference to it (Acts of the Apostles 2:14–38).

50. The Transfiguration of Christ, Crete, mid 16th century, 76.5 · 51 cm, Ikonen-Museum Recklinghausen

51. The Crucifixion of Christ, Russia, 16th century, 31 · 27.5 cm, Zoetmulder icon collection

52. The Resurrection and the Descent into Hell, Russia, 18th century, 30.9 · 26.1 cm, private collection (The Netherlands); detail p. 87

53. Christ’s Resurrection and the Descent into Hell, Russia, early 16th century, 131 · 104.2 cm, IkonenMuseum Recklinghausen

54. The Ascension of Christ, Russia, late 16th century, with silver-leaf revetment, 53.5 · 43.5 cm, Zoetmulder icon collection; detail p. 74

Indeed, it was not until the 17th century that the Resurrection from the Grave – the image of the resurrection we are familiar with in the West – was first made. [52] The Eastern Church draws on the apocryphal Gospel of Nicodemus for its representation on the Easter icon. This text focuses largely on the Anastasis, known in English as the Descent into Hell. The oldest known representation of the Anastasis is on a reliquary from the 8th century, now in the Metropolitan Museum in New York.

In portraying the Descent into Hell, the Orthodox artist aims to represent the essence of the Resurrection: the victory over death and the release from Hell of all those who have been waiting for this moment since Adam. Christ, dressed in gleaming white robes, breaks open the gates of the Underworld. In a variant type, Christ is shown standing victorious on a broken-down cross. Christ catches Adam, the first man, by his left wrist to redeem him from death. The artery in the left wrist was seen as the source of the lifeblood; in this way, Christ gives Adam life. They are surrounded by the risen dead.

Two angels are seen flying in the background among the mountains, carrying a cross as a sign of victory. [53]

The Ascension of Christ is celebrated forty days after Easter. The Ascension icon is based on the version told in the Gospels of Matthew, Mark and Luke and in the Acts of the Apostles (2:1–4). The oldest representation of the Ascension is the Syrian Codex of Rabula, in the Biblioteca Laurenziana in Florence. At the top of the icon, Christ is shown being carried up into Heaven. He has his arms spread out as in blessing. He then disappears from human view. He sits in a circle (an ancient symbol of the divine world), and is flanked by two angels, who appear to be lifting him up into Heaven. This explains how Christ disappears from earthly society. Below, on the ground, stands the Mother of God, with the Apostles and two angels around her. Although the description in the Acts of the Apostles makes no mention of Mary being present, she always appears in the Ascension icon. She personifies the Church, a role that the Church Fathers assigned to her on account of her unwavering belief and her loyalty to Christ. [54]

The feast of Pentecost (fifty days after Easter) marks the moment when the Holy Ghost, the third person in the Trinity, came down to the Apostles as tongues of fire. The icon used at Pentecost is the Trinity icon, not the Descent of the Holy Spirit familiar in the Western Church at Pentecost. An icon with that iconography is used in the Orthodox Church on Whit Monday, the second day of the feast.

The Trinity cannot be represented on the basis of any actually observed form of appearance. Instead, the Church Fathers selected the story of the hospitality of Abraham to represent the Trinity. This is based on Genesis 18:1–16: Abraham and his wife Sarah invite three angels to dine with them. The mysterious ‘Unity in Trinity’ in this story is expressed in the language by a mixture of singular and plural. One of the oldest representations of this theme is a mosaic dating from the 5th century in the Church of Santa Maria Maggiore in Rome.

The icon shows three angels, each with a staff, sitting around a table. The table is set for three people, with cups and cutlery. In the early Christian period, theologians interpreted this representation as a symbol of the Last Supper and the sacrament of the Eucharist. For Russians in the Middle Ages, the Trinity played an important part in their spiritual and worldly lives as a symbol of peace and love. The first day of the feast, Trinity Sunday, is celebrated as a day of reconciliation: people put their differences behind them, remember the dead and talk about the Resurrection. [11]

55. The Dormition of the Mother of God, Russia, early 14th century, 90.3 · 76 cm, Ikonen-Museum Recklinghausen

56. Doubting Thomas, Russia, early 16th century, 81.5 · 51.5 cm, Ikonen-Museum Recklinghausen

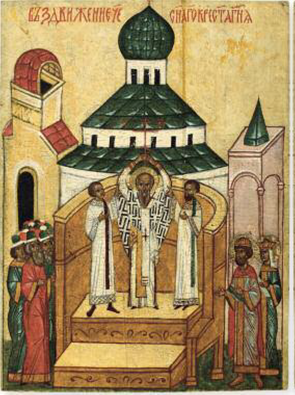

57. The Elevation of the Cross, Russia (Novgorod), late 15th century, 48 · 36 cm, Ikonen-Museum Recklinghausen

The Dormition of the Mother of God is celebrated on 15 August. The oldest representation of this theme can be found on a mural in Atemi, Georgia (904–905). The Bible does not mention the Dormition of the Mother of God, but it was already the subject of a feast in the 6th century.

The Mother of God is shown lying on a bed of state. She is surrounded by the Apostles, who have returned from far-off lands. Behind the bed stands Christ. He has appeared on earth to take his mother’s soul – represented as a newborn baby, resting on his arm – to Heaven.

In the foreground, we see Jephonias. In one story, he doubted the virginity of Mary; in another, he attempted to stop the Apostles carrying her bier: ‘And lo, while they were taking her away, a Hebrew man by the name of Jephonias, strong in body, rushed in and grabbed the bier, while the Apostles were carrying it. And lo, an angel of the Lord with invisible force hewed off his hands with a sword of fire and caused them to hang floating in the air.’ (Pseudo-John, 5th/6th century) Later, when Jephonias feels remorse, his hands grow back again. [55]

The feast of the Elevation of the Cross (14 September) marks the occasion in 325, when, after lengthy excavations, Helen, mother of the Emperor Constantine, discovered the True Cross. The icons show Constantine and his mother, together with a bishop, who is showing the cross to the faithful. [57]

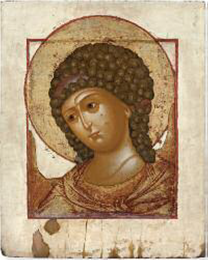

Angels

Angels play an important part in icons. They are seen not only as messengers of God, but also as protectors and saviors of mankind. They create a link between Heaven and earth.

The way angels are represented is based on how gods in pre-Christian times were envisaged. Hermes, the messenger of the gods, was taken as one model: he is usually shown with wings on his feet. In the Old Testament, angels were described as young men, and until the 4th century, they were shown as such, without wings. They begin to appear with wings in the early Byzantine period.

In his Heavenly Hierarchy, known from the 6th century, Dionysios the Areopagite classified celestial beings into nine ‘choirs of angels’: Seraphim, Cherubim, Thrones, Dominions, Virtues, Powers, Principalities, Archangels and Angels. He calls angels ‘messengers of the divine silence’, the silence in which the secrets of ‘He who is’ lie hidden.

Only archangels – and generally only the two most prominent representatives of this ‘choir’, Michael and Gabriel – appear as individuals on icons. [58–59] Guardian angels [60] only start to appear on icons in the 17th century; guardian angels also often appear on the edges of icons, together with the patron saint of the person commissioning the icon.

One icon of the Archangel Michael [61] shows him as leader of the Heavenly Host and warrior against the evil powers who wish to drive the world to destruction. This representation is based on certain passages in the Book of Revelation. Michael, with wings spread and wearing full military armour, sits on a red horse, which also has wings. The horse’s feet do not touch the ground. It flies through the landscape as if it has just suddenly appeared. In his hands Michael holds a Bible and censer. At the same time, with a harpoon, he drives the Anti-Christ (the Devil) back to the Underworld. He holds a trumpet to his mouth. A rainbow appears over his head. In the left-hand upper corner, appearing above a cloud, Christ Emanuel is shown standing behind an altar.

58. Angel Deësis (Michael, Christ Emmanuel and Gabriel), Russia, early 19th century, each 34 · 27 cm, Ikonen-Museum Recklinghausen

59. Synaxis of the Archangel Michael, Russia, 18th century, 45 · 39 cm, Zoetmulder icon collection

60. Archangel Gabriel, Russia, 19th century, 93.5 · 61.5 cm, Ikonenmuseum Kampen; detail p. 94

61. Michael the Archistrategist, Russia, late 18th century, 31 · 26.5 cm, Zoetmulder icon collection

Saints

Orthodox believers have a strong bond with their saints. These saints are ever-present. They are normally invisible, but the faithful can see them in their dreams and visions, and also on icons. The saints on the icons help believers to make contact with the invisible world. Icons of saints always contain some reference to Christ. They are shown looking towards Christ, or there is a very visible reference – a hand, God the Father, Christ or the Trinity – in one of the corners or at the top of the icon. The reference may also take the form of a cross or scroll carried by the saint.

An inscription on the icon identifies the saint in question, while the clothing or attributes show the category to which the saint belongs (patriarch, prophet, apostle, bishop, Church Father, martyr, soldier-saint, hermit, monk or prince). Each saint serves as an example and source of support for the faithful. Saints may be depicted alone or in groups. [62] Sometimes, the life of the saint is told in various scenes, rather like a strip cartoon. These are known as ‘vita icons’. [63]

No saint is as popular, either in the East or the West, as the miracle worker St Nicholas. He was Bishop of Myra in Asia Minor, and is believed to have lived in the 4th century. Nicholas can be recognised from his short grey beard and his high forehead, a sign of great wisdom. The veneration of Nicholas in Russia started shortly before Russia became converted to the Orthodox faith in 988. The cult spread quickly, and no other saint was ever venerated as much. A well-known saying in old Russia was: ‘If God dies, we’ll make Nicholas God’. People believed that Nicholas understood human weakness better than any other saint. He defended them against every injustice and protected them. He also protected travellers if they got into difficulty. He became the patron of countless churches, professions and communities. The reverence in which the faithful held him was almost as deep as that in which they held the Mother of God and Christ. Foreign travellers from the 16th century right up into the 19th century hardly ever failed to mention the special veneration that Nicholas and his icons enjoyed. In the 17th century, people often referred to an icon as ‘a Nicholas’, even if the saint himself was not pictured in it.

62. Marina, St Cyril of Beloozero and St George, early 16th century, 31 · 26 cm, private collection (Belgium)

63. Dimitrij Priluckij with vita, Russia (Vologda), 2nd half 17th century, 100 · 84 cm, Ikonen-Museum Recklinghausen

64. St Nicholas, Russia, 16th century, 24 · 21.7 cm, private collection (The Netherlands); detail p. 100

65. St Nicholas of Mozaisk, Russia, 2nd half 17th century, 31.5 · 27 cm, private collection (The Netherlands)

Many icons of Nicholas were believed to be capable of working miracles and were given the name of the place where they were venerated, such as Nicholas of Mozaisk, Nicholas of Zaraisk and Nicholas of Velikorets. Each of these icons had its own special characteristics. [64–65]

A late-15th-century vita icon of Nicholas of Zaraisk can be seen in the Museum of Icons in Recklinghausen. It shows fourteen scenes depicting the most important events in the saint’s life. How Nicholas was chosen; his spiritual growth, his power over devils, and his help of wrongly condemned people, prisoners and shipwrecked mariners. According to legend, in 1225 the icon of Nicholas of Zaraisk came from Korsun, in the Crimea, to the princedom of Rjazan, where it helped to defeat the Tartars. Nicholas is flanked by two medallions, one showing the Mother of God, the other showing Christ. During the First Council of Nicaea, Nicholas is supposed to have boxed Arius’s ears, because he called into doubt the divinity of Christ. The emperor and the bishops present wanted to dismiss Nicholas from his office of bishop, but the Mother of God and Christ took up Nicholas’s cause and gave him back the attributes of his bishop’s office (the Bible and the stola). [66]

The popularity of George and the Dragon is linked to the military history of Byzantium and the Slavic peoples. George, just like other hero-saints who are pictured as warriors, was very popular with rulers and generals. The dragon miracle is one of the oldest legends in the Eastern Church. George (Georgi in Russian), the son of prominent and well-to-do parents from Cappadocia, was a brave general under the Emperor Diocletian. When he converted to Christianity, he fell from grace and, after being severely tortured, was killed at Nicomedia in 303. According to the 13th-century Legenda Aurea of Jacob de Voragine, which contains many saints’ lives, the city of Silene in Libya was at a certain point terrorised by a terrible dragon. After it had eaten all the livestock, it could only be pacified by human sacrifices. Just when it was the king’s daughter’s turn to be sacrificed, George turned up and defeated the monster in the name of Christ. He killed it only later, when the entire population had been baptised. [67]

66. St Nicholas with scenes from his life, Northern Russia, late 15th century, 92.5 · 71 cm, Ikonen-Museum Recklinghausen

67. St George and the Dragon, Russia (Novgorod), early 16th century, 31.5 · 26.5 cm, Ikonen-Museum Recklinghausen

John the Forerunner is better known in the West as John the Baptist. He went off into the wilderness in the plain of Jordan. There he began to baptise, performing the ritual purification of the ‘penitents’ who heard his call. As a result of his brave actions as a Man of God, he was thrown into prison and beheaded under Herod Antipas. As the last of the prophets, John formed the transition between the Old and the New Testaments. He occupies one of the highest places in the hierarchy of the saints. He is also the great example and the patron saint of monks, who lived as he did, away from the world and devoid of material possessions. He lived in the desert; his unkempt hair falling in long, tangled plaits down to his shoulders. He wore a cloth of camel hair and ate locusts (Matthew 3:4). John is sometimes represented as a winged angel, because, as a messenger, he has a similar role to them.

He holds a chalice in his left hand, in which the Christ Child lays and a scroll. With his right hand, he points to the chalice. The text on the scroll reads: ‘See, the Lamb of God, who takes away the sins of the world.’ In particular, believers called on John to help cure headaches. [68–69]

The prophet Elijah was very popular with farmers. He was seen by the people as the successor to the Old-Slavic god of thunder, Perun. Farmers were very dependent on the weather, so it is understandable that the saint who was felt to control atmospheric forces was much loved. Blaise (Blasios) was also a very popular saint who could be called upon to protect livestock. He was Bishop of Sebaste in Armenia at the time of the Emperor Licinius (303–324). During the persecution of the Christians, he withdrew into the hills, where he lived with the wild animals. [70]

The theme of the Forty Martyrs of Sebaste appealed to the imagination of the faithful and artists alike. The oldest representation of this event is on an 8th-century fresco in the Santa Maria Antiqua Church in Rome. Around the year 320, forty soldiers belonging to the guard of the Roman emperor Licinius had allowed themselves to be baptised. Licinius forced them to stand in an ice-cold river while a bathhouse with steaming hot baths waited on the bank for those who would renounce their faith. One soldier gave in and went into the bathhouse. But one of the guards, impressed by the resolution of the thirty-nine remaining martyrs, took his place. The icon shows the forty martyrs standing close together, maybe to keep each other warm. Many are looking up. The facial expressions and gestures of the martyrs make the scene highly dramatic. The heavens open, and Christ throws down a crown for each of the martyrs. [71]

68. St John the Baptist, Russia, late 17th century, 31.5 · 27.4 cm, Zoetmulder icon collection

69. St John the Baptist, Russia, 17th century, 30.5 · 26.4, Zoetmulder icon collection

70. Blaise and Elijah, Russia (Pskov), late 16th century, 49 · 31.8 cm, Zoetmulder icon collection

71. The Forty Martyrs of Sebaste, Greece, early 19th century, 41.3 · 31 cm, Zoetmulder icon collection

72. Zosima and Savvatij, Russia, 18th century, 31 · 28 cm, Ikonenmuseum Kampen

After the era of the martyrs, it was the monks and ascetics who became the living conscience of the Christian community in the Byzantine Empire. They wished to emulate the martyrs by living exemplary lives, removed from the world. Their great influence and prestige is proven by the fact that many rulers, shortly before their death or on their deathbed, donned the monastic habit. In this way, they would die bearing the signs of Christ’s passion, as these appeared on the monk’s habit.

Two monks who enjoyed great popularity in Russia were Zosima and Savvatij. [72] They wanted to live a hermit’s life, devoted to quiet prayer, like the Desert Fathers of old. To start with, they settled on the uninhabited island of Solovki, in the far north of Russia, by the White Sea. It was not long before other monks, drawn by their ascetic way of life, joined them. A monastery was founded and Zosima (died 1478) became the first abbot. In the 17th century, the monastery developed into one of the largest monastic communities in Northern Russia and exerted a great influence on both the Church and the State. It is ironic that Zosima and Savvatij, who did their best to remain unknown, nonetheless became very popular. They almost always appear in the Extended Deësis row in Northern Russian iconostases. They can also often be found on small metal Deësis triptychs.

Simeon the Stylite was the first pillar-hermit. He lived in Syria in the early 5th century. He wanted to live in solitude, so that he could devote himself to prayer and meditation. However, he gathered such a large group of admirers, who kept asking him for advice and support, that his preferred way of life became impossible. He therefore installed himself on a pillar. Every year, he sat on a higher pillar, in order to keep his admirers at a distance. He ended up living on a pillar 18 metres high. Simeon’s fame spread through the Byzantine Empire and he attracted many imitators. [73]

Another saint with great imaginative appeal is St Christopher (9 May). In the West, he is depicted as a giant who protects travellers. In the East, he was thought to belong to the race of the Cynocephales, who had a human body but a dog’s head. In ancient and early Christian times, people believed that the Cynocephales, together with Satyrs, Centaurs and Sirens, inhabited a world intermediate between humans and animals – creatures who, like people, needed to be evangelised. It is said that Christopher’s ardent prayers to be able to speak human language were heard. [74]

73. St Simeon the Stylite, 1st half 17th century, 63.6 · 38.5 cm, private collection (Belgium)

74. St Christopher with Sophia and her daughters, Faith, Hope and Love, early 19th century, 28 · 24 cm, private collection (The Netherlands)

Most days of the year see the celebration of two or more saints. And since churches did not have an icon of every saint, they used ‘calendar icons’. The oldest calendar icons date from the 12th century, and are preserved in the Monastery of St Catherine in the Sinai. The oldest Russian examples are probably the two great calendar icons in the Museum of Icons in Recklinghausen, each of which covers six months of the year. [75]

Calendar icons show thousands of saints ranked in tiered rows, and meet an intellectual need for hierarchical ordering. But even so, given the countless saints, miracles and feasts that are commemorated and celebrated by the Orthodox faithful, none of these collections of saints could ever be complete.

Together, these saints and feasts formed an inexhaustible source of inspiration for the icon painter. Despite the prescriptions which the painter was bound to follow, every icon is different – whether due to the period in which they were made, their country or region of origin, or the workshop in which they were painted. Even icons that deal with the same theme differ. Where they were made, the traditional style adopted, the artist who painted them, the technique and the material he used make each icon a unique work of art. The beauty and richness of the icons shown in this book may inspire readers to continue this journey through the world of icons on their own.

Note:

A woman from Galicia, who travelled to the Holy Land, c. 381–384.

75. Calendar icons, Russia, 1st half 16th century, each 157.9 · 90.5 cm, Ikonen-Museum Recklinghausen